An exclusive excerpt from the September/October 2021 issue of AMAZONAS Magazine

article & images by Andrew Bogott, except as otherwise noted

Flying with and importing fish may seem like daunting endeavors. However, both are possible if you dedicate a little time, money, and gumption to the task.

Reading Hans-Georg Evers’s description of the Chatuchak Market in Thailand in the July/August 2019 issue of AMAZONAS strikes an uncomfortable note during a worldwide pandemic. It seems like a lifetime has passed since I’ve been in a crowded shop of any kind, much less one in a distant country.

His article also tells another all-too-familiar story: First, Evers begins by asserting that he’s not there to buy and that everything for sale in Bangkok is also available in his home city in Germany. Then, inevitably, he discovers a few tanks containing unusual tetras or a betta form that’s rare or entirely unknown at home. It reminds me of the feeling that I’ve had a dozen times, in an overseas fish store or even browsing online: I see a fish or an invertebrate that I would love to keep, only to realize that they are several customs barriers away from my fish room.

After years of simply browsing Asian fish shops, I finally buckled down and did my research. It turns out that for a U.S. resident, many of the obstacles to traveling with aquarium inhabitants are obscure but surmountable. Here, I will first give some background information on various agencies and services that will help with your importing needs for when the time comes that the spectre of COVID is no longer a concern for international travel. Then, I follow up with my personal experience with transporting aquatic animals nationally and internationally.

Key Players

Depending on where your fish are coming from and where they’re going, a variety of agencies and agents will be involved. Get ready to make phone calls, read websites, and fill out forms. Almost all of these regulations are locally determined, and there’s no reason to think that any of the involved countries have coordinated their policies. So, it’s best to familiarize yourself with all the steps of export and import from start to finish.

With that in mind, here are the folks you might be dealing with if importing fish into the U.S.:

Customs Services in the Country of Origin

To import a fish into the U.S., first it must be exported from the country of origin. There’s no rule of thumb here; some countries care, some don’t, and some require commercial export licenses. Singapore (the only country I’ve personally exported from) has a two-tier system. It considers exports of thirty or fewer fish as a personal allowance that does not require any special permission or paperwork. Some countries may restrict live animal export to licensed commercial dealers or forbid them entirely.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)

As the department in charge of managing livestock disease, the USDA has a strong but selective interest in fish imports. The department does not regulate most tropical fishes, however some fishes, such as carp (including goldfish) and tilapia, require special USDA inspections and certification. The usda.gov website has a page titled “Bring Live Animals into the United States” which provides up-to-date information about restricted species. Better yet, directly contact the USDA officials at your point of entry to see if they have interest in any of the particular species in question. As long as you’re not bringing in food fish or a closely related species, they’re unlikely to be directly involved in the import process.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS)

The FWS is responsible for wildlife and habitat preservation and protecting endangered species. Naturally, they’re going to be very interested in what exact species you’re importing and will want to verify that your fish are indeed what you say they are. If your import isn’t listed by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), then the application for a permit or import license is fairly straightforward.

The FWS only supports imports through a select list of airports called “Designated Ports”. These are the airports with FWS staff available to inspect shipments and baggage. If aquatic livestock are being shipped via air freight, then they will need to travel through one of these ports for inspection prior to being passed on to your local airport. A transshipping service (see next page) generally handles this step. If you are planning to bring animals into the U.S. by air (either as air freight or as personal baggage) and are not traveling via a designated port, then you will need to request an exception or change your travel plans.

| Anchorage, AK | Honolulu, HI | New Orleans, LA |

| Atlanta, GA | Houston, TX | New York, NY |

| Baltimore, MD | Los Angeles, CA | Newark, NJ |

| Boston, MA | Louisville, KY | Portland, OR |

| Chicago, IL | Memphis, TN | San Francisco, CA |

| Dallas/Ft. Worth, TX | Miami, FL | Seattle, WA |

Depending on how many animals you wish to import and what you want to do with them afterwards, you may need an importer’s license. The FWS allows importations for “personal use”, but the terms are quite restrictive and are more geared towards the transport of a single beloved pet. If you plan to trade or resell any of the imported fish or any future fry, then the agency will consider you as a commercial importer who needs a permit. Acquiring a commercial importer’s license is not difficult, but it does involve additional forms and fees. As it stands, FWS declares the importation of eight or more specimens of a given species to be commercial.

Finally, there is a question of timing. The FWS doesn’t inspect every bag or every shipment, but it reserves the right to do so. That means that if you arrive on a weekend, holiday, or outside of normal business hours, you may be on the hook for overtime pay (at least $105) if they opt to inspect. Presumably, the same is true for air freight inspections unless you want your fish sitting on a loading dock until 9:00 am on a Monday.

I’ve contacted FWS officials a few times, and they’ve been consistently responsive and helpful. Many of the above concerns can be resolved via friendly emails, and the necessary forms are readily available on the FWS website. Overall, they do not seem at all hostile to hobbyist imports, as long as you aren’t smuggling snakes in your pants.

Transportation Security Administration (TSA)

I long assumed that the liquid ban imposed on U.S. air travel in 2006 ruled out the ability to transport fish in carry-on luggage, but this turns out not to be the case. According to the TSA’s “What Can I Bring?” website, “live fish in water and a clear transparent container are allowed after inspection by the TSA officer”. The same site says that fish in checked baggage are not allowed but doesn’t provide any additional details.

Airport Security in the Country of Origin

It’s easy to forget that TSA does not govern every airport. Even though air travel security rules are increasingly standardized throughout the world, it’s still important to check local regulations before your departure. The last thing you want is to have a security guard demand that you drop your fish in a trash bin before passing through the metal detector.

Airlines

The TSA has taken on almost all of the responsibility for baggage inspections and regulations for U.S. airlines, but, alas, not all of them. I have yet to encounter one that explicitly bans live fish in carry-on luggage, but it wouldn’t surprise me if some do. Worse yet, in my experience, the airlines tend to be less explicit and coherent about their regulations, so you might get different answers from different officials.

The safest option is to ask in advance, document what you’re told, follow the rules, and don’t do anything to invite extra scrutiny. I once showed up at an airline check-in counter with a box marked “Live Fish, Handle with Care”. The airline official turned me away, and I had to reschedule my flight. If I hadn’t labeled the box, perhaps there would have been no issue.

State Wildlife Officials

State wildlife officials might not maintain a presence at the airport, but many states have local restrictions on exotic animal imports. For example, at least 23 states ban importing or keeping piranhas. There’s no general nation-wide rule; check your local restrictions and be ready to leave most piranhas, Asian arowanas, snakeheads, Gambusia, and snails where you found them.

Retailers (Remote or In-person)

You might be standing in a shop in Bangkok, or you might be browsing an online store a continent away. In either case, the folks selling you fish might be able to cut through some of your importing complications. They may ship regularly to the U.S. and already know the process or have business relationships with people in the U.S. who can smooth things out. If I have the option to pay someone else to navigate the rules and paperwork, I will pay!

Even if you’re talking to a small-time shopkeeper who has no knowledge or interest in international sales, they can still tell you things you’ll want to know. The FWS may ask you where your shrimp were raised, or where your fish were caught. They will definitely want scientific names. Learn and note down all you can, so if someone asks, you’re ready to answer.

Also, don’t neglect packaging. There’s a big difference between bagging a fish for a trip across town and packing one for a multi-day flight. A seller can’t pack fish for a long trip if they don’t know that you’re taking one.

Transshippers

If you want to spend money to make most of these complications go away, then you probably can. Transshippers are businesses or individuals who specialize in understanding import regulations and who already possess the necessary forms and permits to bring animals into the U.S. Typically, a box of fish would be sent to the transshipper via air freight at which point the transshipper receives the package, escorts it through customs, etc., and then sends the fish on to you using a domestic shipping service.

In the easiest case, you’re buying fish such as fancy guppies or bettas from an overseas retailer who already has a relationship with a domestic transshipper. In that scenario, the transaction may be as simple as giving the overseas seller your address and paying the fees. If that seller does a lot of business in the U.S., then the transshipper may be splitting up one international air-freight box and sending many smaller packages all over domestically, in which case the fees may be fairly affordable.

A more bespoke option is to make personal arrangements with a transshipper and then ship a package directly to them. This is the kind of arrangement that hobbyists often use when returning from a collecting trip.

The costs of importing goods through a transshipping service can really add up (international shipping + domestic shipping + service fees for the transshipper), but if you’re not planning to make frequent imports, it may still cost less than buying your own licenses. Plus, it will definitely save you headaches.

Real World Experience: Domestic Travel

I wanted to test the reality of the TSA policy about carrying fish through security. So, a few years ago when I was in Portland, OR for a friend’s wedding, I bought a bag of not-very-expensive Endler’s livebearers (Poecilia wingei) at The Wet Spot Tropical Fish. I told the shop to prepare them for a long trip, stuck them in an insulated lunchbox, and nervously lined up for airport security. As advertised, the TSA agents pulled out the fish, peered at them for a minute, and then sent me on my way. Unfortunately, upon arriving at my home airport, I accidentally left the bag on a bench at the train station. Luckily, after a bit of rushing around and a quick conversation with a policeman, I was able to recover the fish. I’m happy to say that they arrived safely in my fishroom and have since prospered.

I wouldn’t hesitate to repeat this process (minus the train-station abandonment) with a rarer or more expensive fish—it was entirely straightforward. For a single bag of fish, having them as carry-on rather than as checked baggage was more of a perk than a limitation since I was able to maintain control of their handling and transport and did not have to worry about the fish being held for inspection or rule violation.

Real World Experience: International Travel to the U.S.

I spend a fair bit of time in Singapore, where shrimp-keeping is a great deal more popular than here in Minnesota. There are multiple shrimp-only retail shops, and even a random pet store in a shopping mall is likely to have a few tanks full of black King Kong shrimp (Caridina cf. cantonensis var. ‘King Kong’) or painted fire shrimp (Neocaridina davidi var. ‘painted fire red’). Singaporean aquascapers will keep their algae under control with Yamato aka Amano shrimp (Caridina multidentata) if price is no object, but on a budget, they’ll buy a pre-packed bag of 100 Malaya shrimp (Caridina sp. ‘Malaya’) for $10.

Having kept and raised a range of wild-caught Caridina shrimp, Malaya shrimp have become a bit of a white whale for me. They were briefly available in the U.S., but they generally don’t show up on importer lists because they don’t have the bright colors of other domesticated varieties. What species are they? What is their life cycle like? Do they have larval phases or direct development? No one in Singapore seems to really know or care, they’re just cheap workhorses. I, however, wanted to try to answer those questions. But first, I’d need to get some home to a tank where I could observe and photograph them.

A few weeks before my return to the U.S., I started contacting officials. First, I had a friendly email exchange with a FWS official who sent me to the website to fill out some forms.

I also emailed the Department of Agriculture, and they, too, were responsive and helpful. Their response was, essentially, “We don’t regulate freshwater shrimp; you can ignore us”. They also suggested that I get a veterinarian certificate for the shrimp, but that struck me as highly unlikely. Since they didn’t say I needed to get a certificate, I opted to ignore this suggestion.

With the go-ahead from U.S. officials (and my prior positive experience with U.S. air security), the remaining hurdles were related to getting the shrimp out of Singapore in the first place.

Singapore has a personal pet quota for leaving the country with non-endangered animals. It has a personal quota for fish (many), a personal quota for marine invertebrates (no more than five specimens), and no real acknowledgment of freshwater invertebrates. Five shrimp are only barely enough to establish a colony, so I decided to risk it and pack a couple dozen shrimp, argue that they were “fish”, and hope that the customs agents weren’t zoologists.

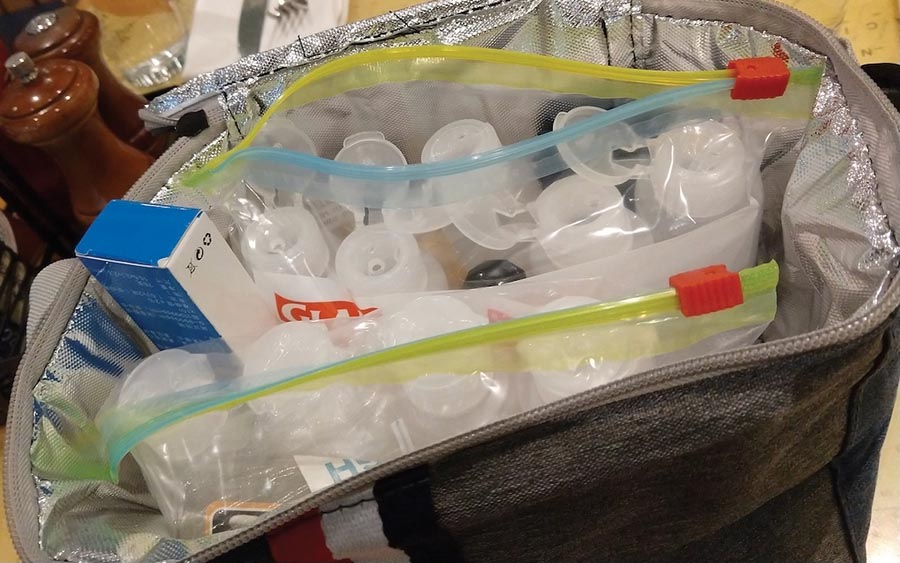

Then, I hit a roadblock. In the U.S., TSA has a special exception to the carry-on liquid restriction for fish; Singapore air security has no such exception. I emailed the Changi Airport security help desk, and their response was curt: “…each passenger may hand-carry up to 10 of the 100 mL (3.4 oz) bottles (total: 1,000 mL). Hence, we regret to inform that it is not advisable to hand-carry live aquarium fish onto the aircraft.” Not advisable, but … not forbidden. The shrimp that I wanted to bring home are very small, and 100 mL isn’t that much smaller than your average fish bag. After visiting a couple of local discount stores, I had a plan: transport the shrimp in 10 separate 100 mL bottles in an insulated cosmetics case.

Finally, I had to acquire and pack the shrimp. Louis Law at Aquatic Glasselli was amused enough at my ambition that he ordered a tank full of shrimp, held onto them for me, and then helped as I packed them up for transport. We placed one or two shrimp in each 100 mL bottle, and I had a decent-sized breeding colony in my carry-on without running afoul of airport security.

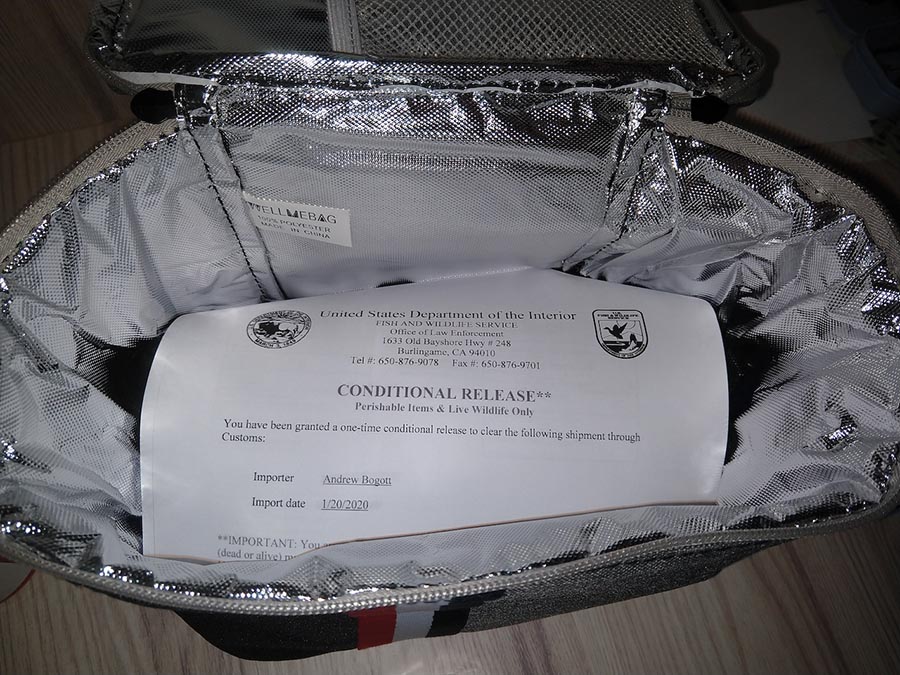

I also printed out multiple copies of my conditional permit from the FWS and prepared to brandish them when challenged. The FWS notified me that they wouldn’t be coming in on the holiday and that the shrimp were “conditionally released” pending further approval.

Getting through security in Singapore was a non-event—they treated my tiny bottles of shrimp just as they would have treated bottles of shampoo. Also, my traveling companion graciously offered to carry half of the bottles, so the 10-bottle limit wasn’t an issue. Once on the plane, there was nothing to do but worry about the upcoming challenge of clearing customs.

On arrival at San Francisco International Airport, I filled out a standard customs declaration at the kiosk and clicked “yes” for the option about declaring live animals or wildlife. The machine printed out an admission form with a giant X over my face and a note to see a passport agent, which was not especially encouraging. After a long wait in an immigration line, the passport agent took my passport and did not give it back. It was alarming, but he promised that someone at the agriculture desk would return it.

Next, I needed to collect my checked luggage and locate the agriculture desk. There wasn’t one, but there was a generic customs inspection desk with another line behind it. After yet another wait, I chatted with a friendly agent and showed her my FWS form. She seemed mostly unconcerned, but “freshwater aquarium shrimp” was definitely a new one for her, so there was a long delay while she shopped the form around among her colleagues. Eventually, she returned and told me that I was free to go.

The rest of the trip was easy. There were no comments from security or baggage handlers, and the shrimp arrived at home alive and swimming. Puzzlingly, the FWS did not officially “release” the shrimp until I filed a few more forms: a flight plan, a receipt, and a personal letter professing my lack of commercial interest. Apparently, it was fine to file these after the fact because a few days later the shrimp were “released”. Of course, by that time, they were already zipping around my aquariums.

Should You Try This?

Overall, my experience hand-carrying fish on a domestic U.S. flight went smoothly. I wouldn’t hesitate to try it again or suggest it to someone else.

My international trip carrying shrimp also went fine, but it’s not entirely clear that I could reproduce the event with the same success. Singapore has especially lenient import/export rules, so traveling from someplace in Europe might be a whole other story. In addition, I don’t know if it was just good luck that I got on the plane without incident or if it was a sure thing.

Also, perhaps shrimp are easier to transport across borders than fish. The USDA might well care about fish, and most fish would be unhappy being crammed into a 100 mL bottle for a day and a night.

That said, I did see the paradisefish Macropodus honkongensis in a tank in Singapore. If they happen to still be there the next time I’m in the region, I may not be able to resist. Of course for ethical reasons, I would want to have flexible travel plans in case I would be turned away at the gate so that I could return the fish back to a local aquarium store rather than tossing it in the trash.

Here are my suggestions for someone else who wants to try an international trip with a fish or another aquarium animal:

- Check in early with FWS and USDA. They are shockingly helpful and indulgent of eccentric desires.

- Read and re-read local rules about exports before setting out.

- Leave the airline out of it. My inclination is to make sure that everything is above board, but airlines are notoriously risk-averse and are likely to say “no” to any question that they haven’t heard before.

- Be ready to assert that your livestock is not for commercial use and mean it. The non-commercial restrictions are a bit silly and clearly unenforceable, but I would hate for people to abuse the non-commercial license exception such that the rules wind up getting changed. If I import livestock again, I’ll probably just buy a commercial license.

- Plan for failure. Failure might mean that you are turned away from your flight, or it might mean that you miss a connecting flight due to long customs delays.

If I Made the Rules

It would be great if all the airlines and all the world’s airline security counters would agree on rules about checked and carry-on baggage. Restrictions on liquids in carry-on baggage seem to be nearly universal these days, but the specifics vary from country to country. Even within the U.S., TSA agents are notoriously capricious, so I will always live in fear of an inspector who doesn’t know about the fish exception and doesn’t want to hear about it.

Rules against fish in checked baggage are frustrating and seemingly arbitrary. I’m unclear whether this ban is simply to prevent baggage-hold chaos caused by leaking liquids (in which case, it would make more sense to have rules about container types rather than container contents) or if it’s to prevent liability after the death of a beloved pet (in which case a disclaimer or waiver system might work just as well).

In general, I’m impressed with how helpful and consistent the FWS has been. The only real headache in that regard is their distinction between personal and commercial imports. It makes sense to me to have restrictions on the volume of imports (perhaps a limit on the number of fish imported per year), but it feels weird to have one species among all my tanks which I’ve promised not to trade or auction. Much like the airline baggage rules, the commercial versus personal labels make sense for those transporting a beloved pet but don’t really comply with the practices of the average aquarium hobbyist.

Hypothetical Scenario

Let’s assume you reside in the U.S. and select the commercial route to import aquatic livestock. First, you must apply for a new commercial import/export permit that is valid for one year. This permit costs $100 and may be renewed annually for the same fee. In addition, each live, non-protected, commercial import will cost you an additional $186 in inspection fees. You also must electronically file the following information with FWS prior to your import’s arrival: species names, count, flight number, and arrival time. Consequently, you will spend at minimum $286 to show your import to a FWS agent at a designated port. Obviously, the more specimens that you import, the cheaper the cost per fish becomes.

Yet, for a traveling hobbyist who desires to bring back only a couple of bags of fish, the $286 price tag is quite steep. As a result, often times fish may enter the country unreported and thus illegally. Maybe a special hobbyist import permit and reduced inspection fees could lower the number of unreported importations. After all, FWS is tasked to protect our natural resources from injurious wildlife and to prevent the trade of endangered species. It would be much easier for FWS to do their job, if a non-commercial legal route existed that encouraged people to comply with the rules rather than smuggling in their aquatic livestock.

Please remember that traveling with fish comes with rules. But even with these rules in place, transporting or importing aquatic livestock may be possible and easier than you think.

Editor’s Note: It is the responsibility of all travelers to be informed of laws governing the transport of aquatic livestock via air travel and across political borders. AMAZONAS magazine bears no liability to those who ignore or are naive to the rules set by officials.

Very interesting.