Seen through the mist: miniature orchids, mosses, and Azureus Dart Frogs flourish alongside a small pond in the office vivarium of Dr. Adeljean Ho.

AMAZONAS editor Matt Pedersen interviews contributor Dr. Adeljean Ho about his office vivariums and how they merge seemingly disparate passions into a harmonious, visually appealing composition

When I finally got a hold of now 32-year-old Dr. Adeljean Ho one late evening in November 2017, he was multi-tasking, busily preparing fruit fly cultures in his kitchen while settling in to discuss his growing passion for the vivarium hobby.

Dr. Ho, a native of Aruba and now a permanent US resident, is a contributor to both CORAL Magazine and AMAZONAS Magazine. Somehow he manages to find time to blend his myriad interests in tropical biodiversity while working as a post-doctoral fellow at Bethune-Cookman University in Daytona Beach, FL. For those who don’t know: in essence, you can think of the role of post-doctoral fellow as the academic equivalent of a medical residency; it’s additional training after you’re awarded a Ph.D., intended to strengthen your research and educational background prior to becoming a professor. In this role, Dr. Ho is currently working with an EPA-funded grant examining the mitigation of estuarine pollution through the use of native vegetation as a littoral buffer.

I asked Dr. Ho about the current state of his personal aquarium hobby: what fish was he keeping right now? “Aside from the tiny fish, none at the moment,” he mused. “The enjoyment of keeping vivariums is the same as keeping a reef, but the maintenance is so much less than a reef system. With my busy schedule, the vivariums fit in way better than keeping a reef tank at the moment.”

Part of that busy schedule includes volunteering: Dr. Ho also plays an active role in the aquarium hobby, currently serving on the Board of Directors as the Director of Industry and Conservation for the Marine Aquarium Societies of North America (MASNA). The purpose of this position is to digest the latest science and legislative news and then help MASNA bring that information to members and the larger hobby abroad. The end goal, as Dr. Ho puts it, is to “build a hobby that is more scientifically literate and aware of its role in both the ecology and conservation.”

Dr. Ho isn’t alone in a life of busy academic pursuits. His wife Nancy, whom he married in 2014, is well-known in some aquarium circles for her ongoing work with a seahorse genetics project. Currently, she is a researcher at New College of Florida in Sarasota, FL.

MP: So, Adeljean, tell me: when and how did you start keeping vivariums? And how do they tie into your past aquarium hobby and interest in fish?

AH: I truly started keeping vivariums last year (2016). My first dart frogs arrived in August of 2016, while I built the vivarium. However, the whole evolution of my hobby started with my interest in orchids. The “frog thing” came as a bonus.

I started keeping orchids when I was 13 or 14, and kept them until I was 18 and came to the US for college. I didn’t keep any orchids during my college years, but I remained current with the literature and enjoyed my parents’ greenhouse when I’d visit home.

It wasn’t until after my Ph.D. was done that I had a big mountain of free time. I hadn’t kept orchids for quite some time, but I had the opportunity to attend the Redland Orchid Fest with my mother. Now, you can’t take someone who used to grow orchids to a festival that big and not expect them to come back with 20 or so orchids. At the time I was living in a small apartment, so I was purposely looking for miniature plants that would thrive in a terrarium environment. What initially started out as a small 20-gallon orchidarium has now grown into a huge system.

The dart frogs largely require the same conditions as the orchids I was keeping. Of course, being a fish biologist by training, I couldn’t set up a system like that, knowing I had to have water anyway, so why not include miniature fish as part of the system? So I just merged all of those interests together.

The ever-expanding collection of vivariums; another smaller system is currently in the works to house more orchids and a smaller variety of thumbnail dart frog.

MP: So how did things go from one 20-gallon tank to an office full of plants, frogs, fish, and fog?

AH: The main impetus for starting up my 20-gallon to house the orchids is that [I] could do it easily. But it took a lot of manual labor. So I quickly moved away from the concept of an orchid holding system that would simply keep up humidity, to something completely automated that would take almost no input on my end.

My hobby went from being a simple glass box to something that is much more naturalistic. What I have now looks like a slice of the jungle.

MP: How did you learn about bio-active vivarium setup?

AH: A lot of my ideas came from reading through different Internet forums, the main one being Dendroboard. When I first got into the idea of keeping vivariums, I was already very familiar with orchid culture. What I wasn’t familiar with was the current technology. The other aspect that I was more concerned with was the dart frogs; I had zero knowledge of them.

So I went to Dendroboard to learn the basic care requirements. I read through different vivarium build threads. I also learned a lot simply through good Google searches; if I find a photograph that interests me, I tend to dig up where that photo comes from, and [I] often wind up on random web pages and blogs that almost no one goes to.

From a technical standpoint, one vivarium I came across was particularly interesting. It was a tank called “The Peninsula,” by Justin Grimm.

(It turns out this same vivarium caught our eye, resulting in a whimsical feature here on Reef2Rainforest.com back in 2014 – watch AMAZONAS Video: EPIC Rainforest Scape.)

Grimm’s tank was the inspiration and technical background to build the vivarium system you’re showing here. This is where I found my internal fan system idea.

Almost everyone in the [dart frog] hobby will say to not have water features in dart frog vivariums, but there seems to be some pretty ingrained and inflexible opinions in the hobby. Things like:

- there seems to be only one way that you should do something

- if you’re not going to do it that one way, you’re not being a good steward

- the whole notion of not mixing locales, species, subspecies, or color morphs – that absolutely has merit, but seems to stem from a misunderstanding of what actual conservation looks like and what a hobbyist’s role is in conservation.

- there’s a lack of balance, where people are essentially line breeding frogs, effectively inbreeding, all while the main argument is that the hobby is arking said specimens.

So keeping some of these ideas in mind, I designed my vivarium more as a “hidden paludarium,” with 85-90% of the available standing water inaccessible to the aquatic inhabitants (the Galaxies and the shrimp), but all that water is circulating underneath the false bottom.

MP: OK, so you keep multiple vivariums and orchid enclosures, but the main one I want to discuss is this one, the 24″ L x 18″ W x 36″ H Exo-Terra. Tell me about the construction process.

AH: The most nervous point for the entire project was drilling the tank. It had to have three bulkheads installed. They’re used for the intake and output of the canister filter for the water area. The one I have is rather small; I wish it was a little bigger. But the next level canister filter is for a 30-40 gallon aquarium, which would blast the fish to death. There’s no sump, so I can’t relieve return pressure unless I dial back the main line and put pressure on the pump itself. This small canister filter works well enough.

The third bulkhead is used as an overflow for the misting system, which is a component separate from the fish’s filtration. It’s designed so that the water level under the false bottom is maintained at a constant height, and any excess water leaves through the overflow.

I use a Mist King misting system, which does the bulk of the work maintaining humidity. It maintains a relative humidity of around 85% at night to 100% saturation during the day once the first misting cycle kicks in during the morning. The reservoir for the overflow is the same size as the one used for the misting system; that way, should something go wrong and the misting system stays on and drains itself, it won’t flood the vivarium, nor the container that catches the excess [and yes, this did actually happen to Dr. Ho during the initial setup, due to a programming error on his part]. At this point, I have almost dialed in the misting system so that I have a net zero impact, with evaporation nearly matching the misting input, but it fluctuates based on the season.

I also have a fogger for the vivarium. It’s a Vicks brand cool mist humidifier that was retrofitted for the system. This isn’t for humidity, but mostly to drop the temperature down when it runs…and it has a cool visual effect.

Shrouded in clouds: the main purpose of the cool-mist humidifiers is actually to cool the internal temperatures of the vivariums. Note the mister, humidifier, and various monitors and controls below the vivariums.

I also have a humidity sensor that triggers the fogger and mister, but it never actually turns on because the vivarium never falls below the target threshold. Still, it’s nice to have the relative humidity monitored. Most of the hobby sensors are accurate only to +/- 10%; I was referred to a different type of module by someone who keeps cool-growing orchids in orchidariums. It doesn’t have a brand name, but you can find it as a DHC100 Digital Humidity Control.

Of course, it requires wiring. And that’s another challenge when building a vivarium. You have to do all the wiring yourself. So that’s a fun thing: you can become a novice electrician while you do this. It’s like when you used to wire your own ballasts and endcaps for your reef tanks.

I’m very typical of the type of person where I think I’m only building one main system, so I’m going to do it the best I can. But it’s all learn-as-you-go. It’s kinda scary and difficult because most people don’t intend on setting up 10-15 systems…so you try to do it all right the first time.

Orchids generally require air movement to prevent disease. This is a great look at the internal ductwork for internal air circulation, constructed out of corrugated plastic. Air is brought in underneath, then circulated by a computer fan and exhausted in two directions at the top. Also note the pots, which include draining tubes to bring excess water down to the substrate and eventually the water table underneath the false bottom.

Great Stuff Pond & Stone foam is applied to the background; it will then be carved and coated with silicone that is dusted with organic materials like peat moss or coconut husk fibers to create a natural, dirt-like finish.

The foundation for the back wall of the vivarium, now foamed and covered to create a natural backdrop while concealing the air circulation system and drainage for the pots. Note the three cutouts at the base, in place to accommodate the bulkheads that move water and handle excess from the water under the false bottom.

The background, shown in position. Note that the fan remains accessible via the opening at the top of the ductwork (this is actually sealed by the glass lid once in place, but allows for the fan to be serviced or replaced if it fails).

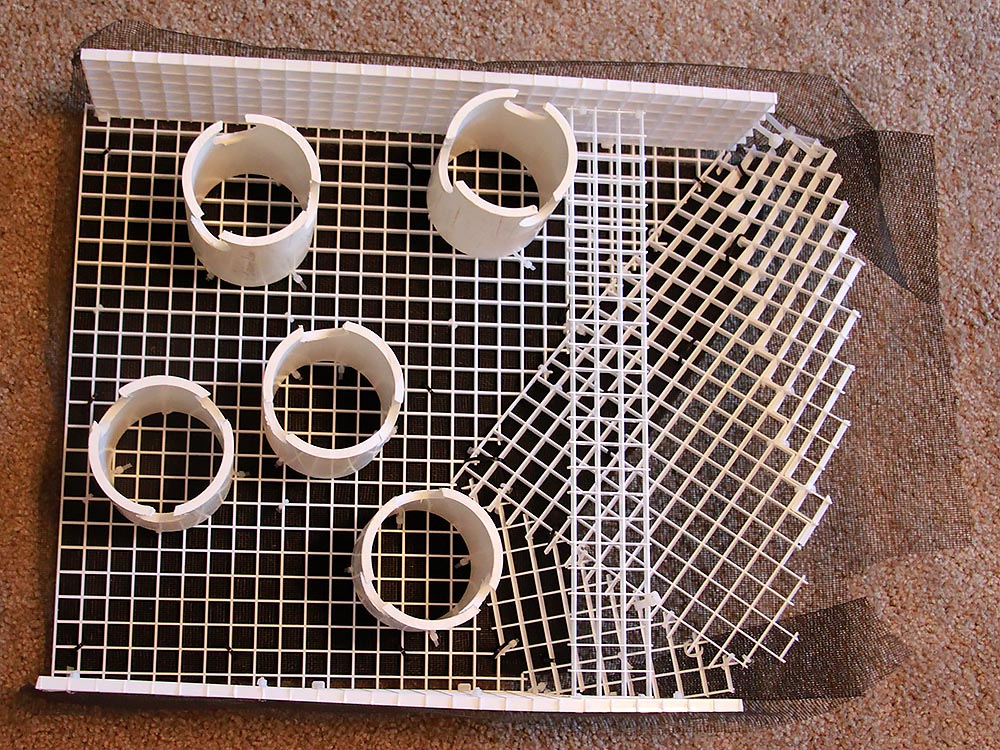

The false bottom, constructed of an eggcrate lighting diffuser, window screen, and thin layers of filter foam, allows water to flow freely underneath to filtration systems and overflows.

The underside of the false bottom reveals sections of PVC pipe used as support legs. Note the notches cut in the bottoms; these allow water to flow down, through, and out of the pipes.

Water testing. Note that the false bottom stops short and does not extend to the very edge and the glass. Fluval substrate is added alongside to conceal the structure from view.

Continue to Part 2, where we examine the orchids, epiphytes and other plants flourishing in this vivarium.

Learn more about keeping fishes and terrestrial life together in the January/February 2018 issue of AMAZONAS Magazine: PALUDARIUM PRIMER.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks