Pterygoplichthys gibbiceps, known as the Sailfin or Leopard Pleco, part of a genus spreading in tropical waters around the globe. Image: ET1972/Shutterstock

Preview of article from AMAZONAS, May/June 2018

Notebook Staff Report

Florida fishermen and naturalists have known for years that many local waters are infested with invasive “plecos,” which are blamed for competing with native species, eroding shorelines with their burrowing behaviors, and even harassing endangered manatees by swarming over their moss-covered backs.

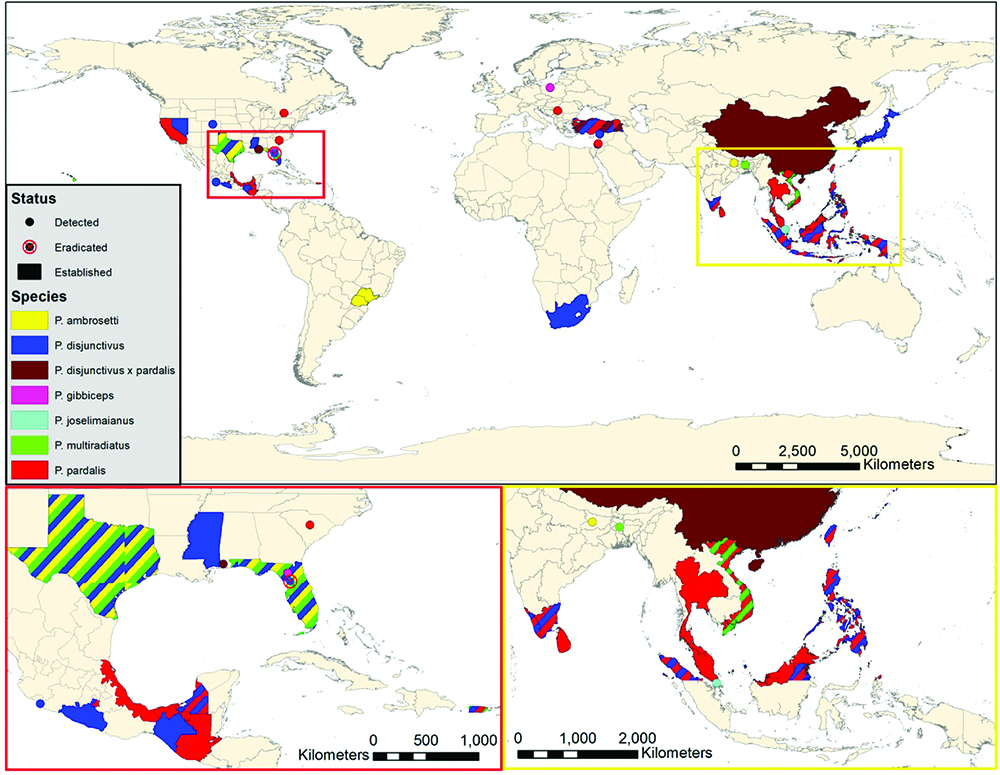

Now a new study attempts to document and map the global spread of Pterogoplichthys armored catfishes in places from many points in the United States to the Caribbean, the Middle East, and huge swathes of Asia, including India, China, and many islands in Southeast Asia.

The eye-opening report, by Alexander Orfinger and Daniel Goodding in the Biology Department of the University of Central Florida, Orlando, entitled The Global Invasion of the Suckermouth Armored Catfish Genus Pterygoplichthys, appears in the journal Zoological Studies (57:7).

Non-native Pterygoplichthys (16 individuals visible) gathering around an adult female Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) and her yearling calf at Blue Spring Run, Volusia County, Florida. The catfish often settle on manatees, apparently to graze on algae and other epibionts growing on their skin; note the near absence of epibionts on the manatees, which normally have algae growing over their backs. Many of the smaller pale fish, barely visible, are juvenile Bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus). Photograph by James P. Reid/USGS

According to the authors, “The genus Pterygoplichthys includes several popular aquarium species that have become invasive in tropical, subtropical, and warm-watered regions around the world.” Commonly called armored sailfin catfish, janitor fish, peces diablos (devil fish), or “plecos,” species of the genus exhibit most of the characteristics that predispose certain fishes to successful invasion. This suite of biological traits include:

(1) high fecundity

(2) broad physiological tolerance (i.e., salinity, pollution, and hypoxia [i.e., enlarged, hypervascularized stomachs that allow for air-breathing and survival for up to 30 hours out of water])

(3) rapid growth of 10 cm/year

(4) an armored exterior with powerful pectoral spines

(5) life span of more than five years

(6) high aquarium-vectored propagule pressure.

Regarding the final point, they say: “Human-mediated factors foster the spread of Pterygoplichthys spp., namely the popularity of members of the genus in aquariums and subsequently aquaculture, contributing to high propagule pressure. Once established, these fishes are extremely difficult to remove.” Other biologists have attributed the widespread invasion of plecos in the state of Florida to escaped stock from fish farms, also fueled by releases of unwanted specimens by irresponsible aquarists.

In researching the impacts of plecos getting into non-native waters, the authors used something called the “generic impact scoring system,” or GISS. The recorded or reported fallout from a pleco invasion in a geographic region includes both socioeconomic and environmental changes. The study attempted to find published reports on all valid species in the genus Pterygoplichthys (Fishbase currently lists 22 species in the genus), with a number of fish sold in the aquarium trade as plecos or sailfin catfishes. Their map shows the spread of six different species and one hybrid.

Impacts reported included displacement or elimination of native fishes, being a vector for nonnative parasites, damaging fisheries equipment, acting as egg predators of native fishes, reducing fish food resources (e.g., aquatic insects and aquatic vegetation), and decreasing yield of desirable food fishes and shrimp. In many places, the breeding habits of these catfishes have caused serious issues where males burrowing in soft substrates to build spawning caves have led to shoreline erosion.

As for the Florida manatees, the USGS biologists concluded: “Manatee responses (to be grazed upon by invasive plecos) varied widely; some did not react visibly to attached catfish, whereas others appeared agitated and attempted to dislodge the fish. The costs and/or benefits of this interaction to manatees remain unclear.”

Sources

The Global Invasion of the Suckermouth Armored Catfish Genus Pterygoplichthys (Siluriformes: Loricariidae): Annotated List of Species, Distributional Summary, and Assessment of Impacts

Alexander Benjamin Orfinger and Daniel Douglas Goodding

Zoological Studies 57: 7 (2018) doi:10.6620/ZS.2018.57-07

Published 14 February 2018

Interactions between non-native armored suckermouth catfish (Loricariidae: Pterygoplichthys) and native Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) in artesian springs

Leo G. Nico, William F. Loftus, and James P. Reid

Aquatic Invasions 4:3 (2009)

What the pleco really needs is a good PR campaign. The logical solution to this problem is to establish a Southern equivalent to the famous New England Clam Bake: a Pleco Bake (I hear eating plecos is much like eating lobster in terms of cracking open the shell and pulling out the meat). Once you convince people that plecos are food and there’s no such thing as overfishing, you create a market demand. They’ve been doing the same with lionfish—there are restaurants who desperately crave a supply. The reason invaders like these get a foothold is because native predators can’t or won’t eat them. As such, we need to create a predator: us.

Get a few cooking contests on food network to prepair plecko and telivize a few recipies allong with a story on how they were caught for FREE sit back relax as kegs of bros go out catch and eat them … because