Taking a new aquarium from concept to reality can be a good time to contemplate “big picture” ideas in fishkeeping: one of the author’s new tanks during setup.

I recently had the chance to set up some new aquariums at home, a few of which spent a long time in the planning stages. After the exciting/stressful phase of bringing in a fair number of fish to stock these tanks, I’ve had a few weeks now to sit back, enjoy the results, and observe the fish interacting with their new habitats—for me, far and away the most rewarding part of the hobby. And during the “settling in” phase, when I think every hobbyist spends a little extra time anxiously watching their new charges, I got to thinking about fish behavior in the aquarium setting. More specifically, about the subtle ways that behavior changes when fish are taken from a complex wild habitat and placed in (generally) less complex glass boxes. With the two new aquariums I set up at home, I hoped to see if this could be prevented as much as possible.

Scenes like this one, with a diverse group of species all living in one microhabitat, can be difficult–if not impossible–to completely replicate in an aquarium

If you spend some time observing aquarium fish in the wild, you get a feel for the interesting things fish do that you rarely, if ever, witness in an aquarium. Huge mixed schools of Characins—Cardinals, pencilfishes, Bryconops, even baby predatory species like Acestrorhynchus—all moving as one through extreme shallows, or roving packs of large cichlids like Uaru, Crenicichla, and Cichla spp. hunting together with a few Eartheaters trailing closely behind to pick up scraps.

These scenes tend not to work in the home aquarium setting, either due to space limitations or the fact that the same group of fish are confined together permanently, where in the wild these mixed species aggregations would dissipate and then regroup based on changing conditions and food availability. But there are other, no less interesting but more practical behaviors, which, given the right conditions, aquarium fish can be reasonably expected to display.

A small group of dwarf cichlids (Dicrossus maculatus and Apistogramma sp.) patrol a submerged branch in the Tapajos

This includes hordes of Apistogramma and other dwarf cichlids cavorting among the leaf litter, defending territories, building leaf “forts” by dragging fallen leaves roughly twice the size of the fish itself and placing them into neat piles or fighting over a particularly desirable leaf (quite the comical sight). Or other species, especially checkerboards of the genus Dicrossus, acting like little sentries perched strategically on a fallen log or submerged tree root against a current, intently watching all passersby. Even species not exactly known for their outgoing nature (plecos, anyone?) often exhibit rather different behavior in their wild habitat.

I recall searching for plecos on the Rio Xingu by peering into cracks in the rock formations, only to find that the resident plecos would typically come charging right out at me, fanning their tails in a threat posture at a human hundreds of times their size. It is also not uncommon to find stick catfish in the genus Farlowella or Acestridium busily “climbing” fallen branches against a powerful current, grazing on algal or bacterial films in small groups.

Rock-dwelling pleco in the Rio Xingu. When approached, these fish often boldly swim toward the “intruder” to defend their territory

So, with the goal of “bringing out the best” in my fish, behavior-wise, I set out to see if replicating their wild habitat as closely as possible would get them to behave, essentially, as they would in the wild. And so far, the answer has been a resounding “yes.” Here are some highlights:

My Rio Xingu tank included a lot of rockwork, with both vertically– and horizontally-oriented crevices and caves, and lots of current to replicate the fast-moving waters of that powerful river. Despite the abundant hiding places, the plecos are out in the open more often than not, displaying to each other and defending their various territories among the rocks. I’ve kept various Gold Nugget Plecos (Baryancistrus sp.) in the past, and it was rare to actually see them in the aquarium while the lights were on. I’ve been very pleasantly surprised at how, in this setting, they are both visible and interesting to observe.

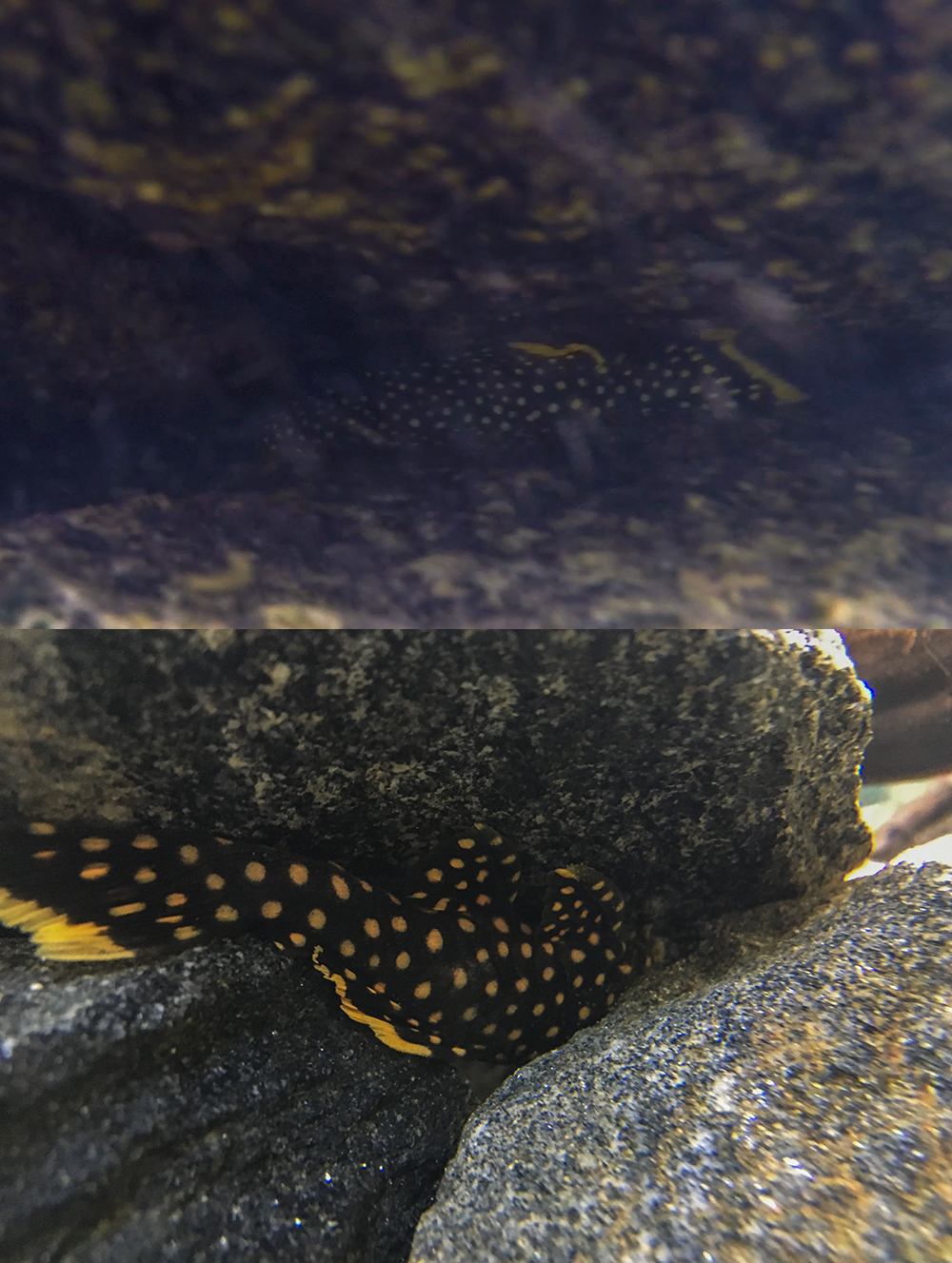

L177 Gold Nugget Pleco in the wild (top) and in the aquarium (bottom). When kept in a setup similar to their wild habitat, these fish are bold and often emerge from hiding to explore their surroundings during the day

Current, naturally, plays a big role in this tank. I have four juvenile Retroculus xinguensis, an eartheater relative which is highly adapted to the fast-moving waters of its native habitat. These fish are easily among the most active cichlids I’ve ever kept, gliding in and around the current produced by the filter output and propeller powerhead effortlessly. They also spend a substantial amount of time sifting through the substrate (a fine sand and pebble mix), like their relatives the Geophagines.

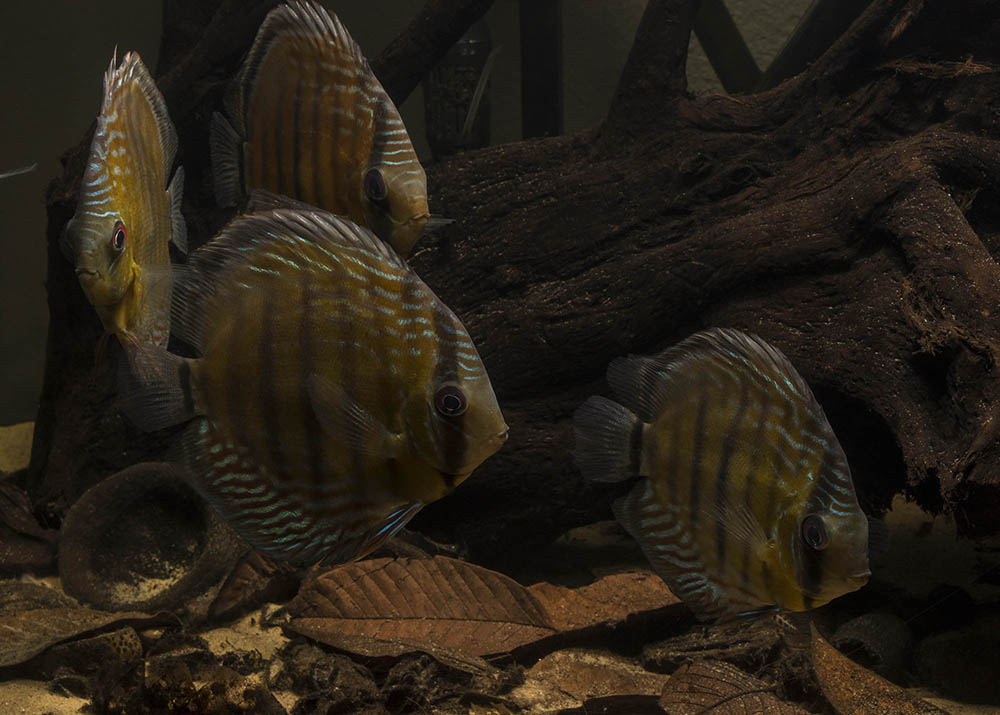

The other tank was inspired by Lago Grande do Curuai, a clearwater “lake” on the lower Tapajos river and designed to replicate typical discus habitat there. Structure is provided by a massive driftwood root mass, and the discus orient themselves around it just as they would in nature.

I also used a wide assortment of botanicals from Tannin Aquatics in this tank, including Guava and Ketappa Leaves, to replicate the leaf litter typically found in this type of habitat, as well as a number of seed pods and accent items. These are not just decorative: they serve a functional role as they offer cover, visual barriers, and territory “anchors” that my Dicrossus and Biotecus dwarf cichlids can use, manipulate, and move (which they do).

Another wild/aquarium comparison with checkerboard cichlids. The use of botanicals like leaf litter can promote natural behaviors in many fish species

The botanicals and driftwood both cultivate biofilms, which is actively grazed on by all of the fish in the tank. The discus, especially, spend a good portion of the day nibbling at decaying leaves, which matches what you would typically find in the gut content of wild discus: detritus, leaves, and other plant matter, with only a relatively small proportion of insect larvae and crustaceans.

While I will likely go into more detail about these two tanks in later posts, I use them here as demonstrations of how to elicit more natural behavior in aquarium fish by offering them a more naturalistic environment. I certainly don’t think it is necessary to go “full biotope” for this to happen—i.e., strictly using plants and fish from the same locality or habitat—but I do think making a general attempt to replicate conditions fish encounter in the wild will help bring out the best in them in an aquarium setting.

I would also add that complex habitat generally seems to favor complex behavior, so the minimalist approach to aquarium decor may not be doing your fish any favors. I’ll never forget the first time I encountered a pair of massive “Jurupari” Eartheaters (Satanoperca leucosticta) as a teen at one of the local shops near me, cruising listlessly through a huge, bare-bottom display tank. The fish were beautiful, healthy, but both boring and likely bored—without a fine sand substrate for them to sift through, there was no way for them to exhibit their unique feeding adaptation of sucking up mouthfuls of sand and filtering it through their gills in search of food.

When given complex habitat to interact with, even “shy” species like the Butterfly Pleco, Dekeyseria brachyura (L168), will often become surprisingly bold

Remember, most of the freshwater fish we keep in aquariums come from incredibly complex habitats, constantly and often drastically changing, influenced by an annual flood/drought pattern. They have evolved and adapted specifically to these dynamic environments, and they often to take advantage of very specific niches in both habitat and feeding methods. As a rule, their behaviors reflect these dynamic, intricate ecosystems. In general, the aquarium setting—a static, relatively simple environment—is not conducive to keeping fish stimulated enough to bring out these behaviors. As my recent forays into more naturalistic aquariums have demonstrated, however, it is possible to bring out your fish’s full potential, to bring out the best in them, with some careful aquarium design, creativity, and knowledge of both how and where these species live in the wild.

Thank you Mike for the very interesting, informative and thought provoking article. I have an empty 150 gallon tank that is waiting for me to fill. I am torn between South America and South East Asia. Not decided yet.

Wonderful piece. Hard at first blush to think about how to respond without seriously large tank size – would be interesting to see a follow up on the how-to, particularly with smaller (less than 50 gallon) tank sizes (if possible).

Thanks Mike! We hope to make that a reality very soon with some follow up pieces. Given the very small spaces some of these microhabitats take up in the wild, I think it’s entirely possible to create very naturalistic aquariums in even nano aquaria. I had a wonderful leaf litter aquarium in a 14-gallon tank full of small species found in the extreme shallows of the Rio Negro.