This photospread starts with the story of inadvertently ordering the wrong fish, and ends with what I hope are helpful insights into one of my favorite photography techniques.

The Rainbow Shiner, Notropis chrosomus, had been on my watchlist as a possible candidate for my container ponds this summer. It is apparently now a targeted native species in the freshwater ornamental fish industry, being produced by at least one Florida fish farm. I’d seen it available on and off all spring and summer this year.

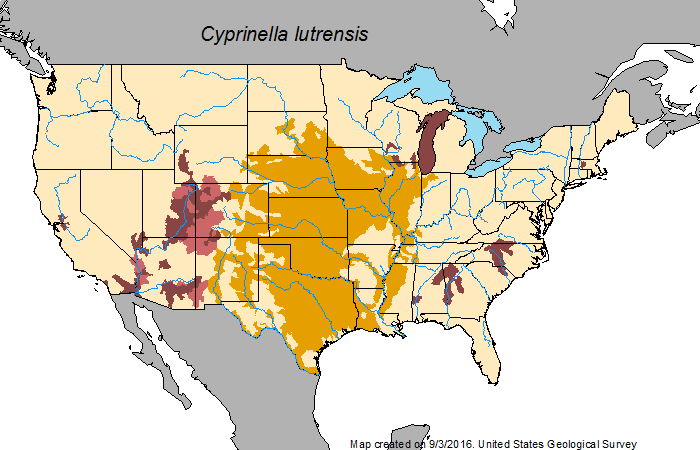

The Rainbow Dace, Cyprinella lutrensis, is also known as the Red Horse Minnow or the official common name Red Shiner. It has been in the aquarium hobby for quite some time now. In fact, it’s the first native fish species I kept when I was just a child, caught out of the waters of a Southeast Wisconsin lake. As a child, I found them truly indestructible. The Rainbow Dace has a much wider distribution than the more coveted Rainbow Shiner, and has been introduced into many locations outside of its native range in the US.

When I placed the order for my Rainbow Shiners this spring, I obviously wasn’t paying close enough attention to what came after the word “Rainbow” on the list, so all summer, I’ve had the opportunity to revisit a species I’d already kept in my youth, the Rainbow Dace. Initially I was quite disappointed with myself for having made the mistake, yet a few months have passed, and I certainly have a deeper appreciation for this species.

Merits of the Rainbow Dace

I always wrote this species off as a “minnow,” not exotic enough to warrant interest. In fact, this species is commonly used as a baitfish for fishing (which is often cited as the means of translocation to areas outside its native range). It’s something so “commonplace” and “cheap,” something that hypothetically could be picked up at the local bait and tackle shop by the dozens, that it’s probably unworthy of an aquarist’s attention, right? Plus, it’s a native and naturally temperate species; both of these facts tend to suggest that this isn’t a species we can mix in our generally warm, tropical aquaria.

Ironically, so many of the fishes we lust over from pretty much any other continent are certainly “minnows,” at least in the same context as our Rainbow Dace. Frankly, compared to something like a Pearl Danio or Emerald Eye Rasbora, arguably the Rainbow Dace wins in the looks department. I hope the photos here help to emphasize that point. Now, these Rainbow Dace seem more vibrant than the ones I caught as a child. Are they simply an improved aquarium strain? Could it simply be that they are getting a more carotenoid-rich diet than those wild specimens? Could they be more comfortable in this dimly-lit and algae-covered aquarium, versus the bright white background of the tank I kept them in some 25 to 30 years ago? Or were they always this attractive, having faded only in my memory?

Rainbow Dace are awash in blues and salmon pinks and oranges, truly rivaling many other freshwater fish in the looks department.

I’ll never be able to answer that question, but, regardless, this is a species worthy of another look. It also seems to be a species where misinformation comes into play. For example, one source suggests that these cannot tolerate temperatures below 58F, which seems odd given the natural range of the species (they certainly don’t swim south for the winter). Another suggests that maximum temperatures cannot exceed 71F, which is equally puzzling, given that mine are thriving at 72-76F; certainly the lake I caught them in decades ago easily reaches bathtub-level temperatures! 78F is given as a max temperature by some; I’d simply add that these active fish certainly require high levels of aeration to maintain high oxygen levels, particularly in warmer aquariums.

Given the diverse range of suggestions applied to these species, I’d probably suggest turning to NANFA’s care sheet on Satinfin Shiners as the most reliable source of basic husbandry and breeding info. I’ve once again found my Rainbow Dace to be completely undemanding.

A lone Rainbow Dace, while a worthy photographic subject, is probably a lonely and neurotic tankmate.

Suggestions that they should not be kept with Goldfish may be overly cautious; I housed mine in an unheated aquarium in the fishroom along with a pair of Orandas destined for our neighbor’s pond (if we ever get that repaired). All the concerns about these being “fin nippers” failed to hold up, but I suspect the reason is simply that I kept the fish in a group. The Rainbow Dace is definitely a shoaling fish, and I could easily see it turning into a fin nipper if it were not constantly preoccupied with other members of its own species. Keeping a lone Rainbow Dace would not be something I suggest; others recommend 3-4 as a minimum, but I’m going to say you should start with at least half a dozen, ideally more. The following photos might sell you on that notion.

“Shooting in the Black”

Years ago, I purchased an external flash that is corded. It was designed to be mounted on a rail attached to the camera, or to be used as a hand-held flash (which is how I always use it). This flash is much preferred to the on-board camera flash, although by default, the light it provides is somewhat directional and can at times be rather harsh. On the flipside, it can be used to create rather dramatic lighting. Ultimately, the flash is simply a tool — how you use it determines the outcome.

When it came time to photograph the Rainbow Dace in the fishroom, I had to utilize one of my favorite techniques. The aquarium they were housed in is covered in algae (I let it grow) and simply isn’t visually attractive. Sure, I could remove the fish from the tank and place them in a black photo tank, but often that stresses the fish out, which causes them to lose coloration and become uncooperative photo subjects. So how could I photograph these fish in an unattractive tank, without you, the reader, ever knowing?

When using this lighting technique in his fishroom some years back now, Ted Judy called it “Shooting in the Black.” I hadn’t heard of it quite that way before, and searching for “shooting in the black” turns up quite few completely unrelated news stories. More appropriately, this technique is simply using the principals of light fall-off to highlight the subjects (the fish) and de-emphasize everything else.

If I simply lit the tank from the front with any flash, I’d get a photo that isn’t really appealing, like this one:

When lit from the front, the fish, while nicely highlighted, sits over a visually unattractive algae-covered tank wall, with seams and cords in the photo. A different lighting approach is required to get a nice shot!

Light fall-off, whether from natural light or, in this case, from a flash, allowed me to squarely make the fish the focus of my photos. There are some great online articles that present this concept, but perhaps none illustrates it more clearly than this simple Flash Fall-off Cheat Sheet. You may also enjoy reading Photography: Using light fall-off to illuminate your subject and Working with Fall-Off.

In the case of “shooting in the black,” I achieve the greatest disparity between the fish and background by positioning the flash as close as possible to the fish, but also by using the directional nature of the flash in this setting to purposely not light the background of the tank. Generally, this means placing the flash straight overhead, or possibly ever so slightly in front. If you put the flash behind the fish at all, you get an unrealistic amount of debris showing up in the photo, along with a completely back-lit fish.

On my Nikon, I generally just go with a shutter priority setting of 1/200th or faster, and I adjust the flash’s intensity manually to fire at roughly 1/4 of full strength. Here’s how it looks in context:

One of the biggest downsides to this technique is that it illuminates everything in the water column very well. Therefore, there is a bit of post-processing in Photoshop required to take an image from the camera into a final format. Here’s a quick example of the workflow:

Finally, I use a single pass of a very light sharpening filter to bring the fish into crisp focus (due to the nature of digital photography, some people argue that all digital photos require a sharpening filter to some degree). The debris in the water is removed manually using the spot healing tool, and my final photo is complete.

If I wanted to take this a bit further, I could apply the techniques I wrote about a few years back, removing all the background from the photograph and putting the fish onto pure black. As it stands, I don’t mind seeing a little bit of my dirty, algae-covered substrate. It grounds the compositions.

Seeing just a hint of the tank bottom anchors the fish in this photograph, as opposed to being fish floating in total black nothingness.

Of course, something about that last photo just bugs me; I don’t like that blurry fish facing the camera. Perhaps next time, I’ll show you how to use a “content aware fill” to fix that, like this:

Have you kept Rainbow Dace? What conditions did you provide for them? How did your experiences compare to my own? Tell us in the comments below!

I catch these same “redhorse minnows” (as we call them) in the small canal in front of my parents’ house in rural Southern California in the desert. These guys are thick in the canals and definitely can tolerate super hot temperatures as the shallow canals get baked by the 115*F to 120*F weather we get here. I have put them in a 20 gallon tank and just love their active personalities and their colorful flash. I am debating cleaning out my native + oscar 55g tank (I have 3 bluegill and a small largemouth bass that I caught at around 2.5″ and he’s now almost 6″) and selling/giving away the oscar and returning the natives back to the canal so I can catch some more redhorse and do a heavily planted tank with these guys shoaling around.