The elements of fall simply overwhelmed the shallow pond by early November.

Despite getting a late start on my outdoor container ponds in 2015, it proved to be an enjoyable and successful first season. I alluded to both successes and failures that first year, so here’s how things went, and some lessons I learned along the way.

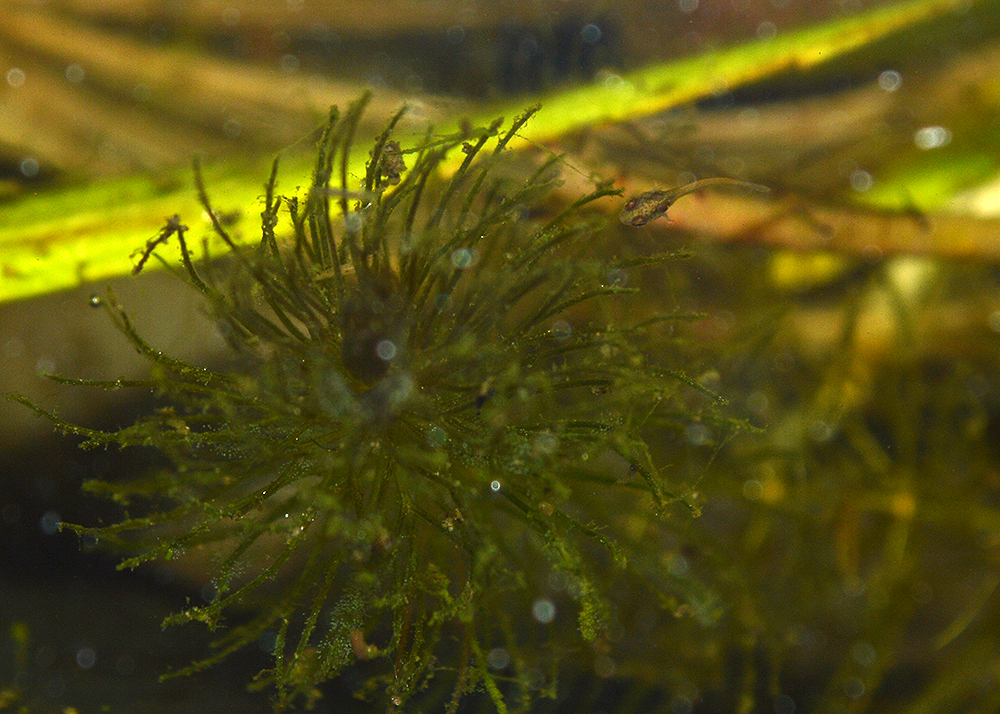

The Still Pond, photographed in late summer (9-13-2015). Water Lettuce grew fast, and I had removed a lot of the floating Golden Moneywort in preference to the Hornwort.

The Still Pond

You may recall that this pond was nothing more than a full-height (or is it full-depth?) MacCourt Whiskey Barrel Liner with a heater in place and an assortment of unattached aquatic plants growing in it, including Java Moss, Water Lettuce and Golden Moneywort. I had stocked this tank with Betta smaragdina “Guitar,” one male and several females, in the hopes of seeing a lot of reproduction.

As it turned out, I never saw a fish after the first 48 hours. I knew this species was known for being rather cryptic and hiding, so I didn’t let that alarm me; I kept feeding the pond with flakes and allowing the mosquitoes to do their thing. However, despite months of checking, I never once saw a bubble nest built in the floating half styrofoam cup. As fall approached. I removed much of the vegetation in search of fish, but never found anything. When it came time to drain the pond, I didn’t find a single fish. Clearly, this had been a failure.

A large diameter siphon makes draining go very quickly; a net placed at the other end catches any debris and fish, although none were found.

I’m not sure what occurred in this pond, but I have a couple of ideas. First, I noted that the water rapidly stratified into hot and cold; while the surface temps could be in the upper 70’s, the water at the bottom of the pond was significantly cooler, possibly a 10-degree difference or more (I am using my built-in personal aquarist’s thermometer, AKA my hands, to guess the water temps).

The depth of this pond may have been a further contributing factor to the failure of this project; in those first couple of days, I never saw the Bettas at the surface, but always farther down. This suggests that they were shy, seeking refuge deeper, which likely put them in uncomfortably cooler waters. The depth may have made the male uncomfortable about creating a bubblenest as well.

The other possibility is perhaps more grim: it could simply be that disease broke out in the pond and killed the fish. This is entirely plausible, given that it’s almost impossible to observe the health of a fish you can’t see anyway!

The Shallow Pond

Things went surprisingly better in the shallow pond, which had ironically only been set up to hold some plants I thought I’d use in the other ponds.

This pond was set up to house a pair of Betta mahachaiensis with the hopes of getting them to breed and perhaps even seeing babies just grow up within. In fact, this pond did make progress towards that goal: it appeared that both Bettas opted to hide among the large pots at the rear of the pond most of the time. On rare occasions, I’d even catch a glimpse of the male or female sitting out in the open. Bubble nests appeared somewhat regularly.

I made it a point to occasionally add in Vinegar Eels or newly-hatched brine shrimp as fry feeds, as I could only assume there were baby fish being produced. On occasions, close observation confirmed these suspicions.

Despite being off to a good start, this pond had its own share of setbacks. For starters, it evaporated very quickly compared to the other two ponds, which caused me to routinely bring out the hose, which was only cold water. I’m not exactly a fan of instantly mixing 70-80F water with 50% tap that’s probably 50-60F at the warmest; still, the Bettas seemed to persist through that hurdle.

More problematic were the critters. I routinely found this pond’s plants knocked over, the dirt in the pots clouding the water and otherwise just making a mess of the pond. Still, the Bettas survived.

However, as the season progressed, cold rains and leaves continued to inundate the pond.

By the end of the season, the Betta offspring had all vanished from the pond. Clearing out the pond revealed nothing. I thought I still had my adults present in the pond, however, because I was still seeing what I thought were bubblenests being built on the surface of the now-coffee-colored water.

It was only after cleaning out the pond, and then draining what remained through a net, that I discovered that the Bettas were somehow not present. Perhaps they had been snatched only a day or two before, or perhaps what I had thought were bubblenests were simply bubbles created through other means (e.g., rain splashing in now heavily organic-laden water). Despite the apparent loss of all my Betta mahachaiensis, I did discover a resilient Otocinclus, which I had placed in the pond to keep algae off the rocks.

I took the plants from this pond into the fishroom, placing them in a partially-filled 10-gallon aquarium that would receive daily light. It remained to be seen how they would fare through winter and into my second season of container ponding.

The Shelf Pond

The Shelf Pond was arguably my most successful pond, but it too had some issues.

Despite the introduction of the Corydoras and Otocinclus, it appears most of them died early on. I never found all the bodies, but I did find a few within the first week after I added them. I can only suspect disease; again, only being able to see from the top through an agitated water surface makes observation very difficult.

The Black Phantom Tetras excelled in this tank; I saw spawning occurring near the surface in the floating plants on more than one occasion, although I never did notice any fry. The use of the Sicce Shark ADV internal power filter may have precluded that from being a possibility anyway. As the summer wore on, the tetras remained active and provided a great dark contrast against the light sand substrate.

A couple females disappeared during the season; at least one was found dead on the ground, and it was unclear as to whether it had jumped or had some help from the local wildlife. It was amazing to compare how much darker the Black Phantoms became outdoors, versus those from the same group kept indoors under only ambient light conditions.

A close-up look at the Black Phantom Tetras in the shelf container pond; females can be differentiated from above by their shorter fins and red pelvic and ventral fins.

By late fall, the water had become significantly tannin-stained from the leaf litter falling from the maples and other backyard trees. I left the shelf pond up well into mid-November, pressing my luck, just to see how this would go.

Indeed, this pond made it through snow…

I think after a few snowfalls, I realized I probably was pressing my luck (it was already late for our first real snow to stick around).

Draining this pond was rather quick, and I simply left everything in place for the winter. While I tried to cover the Still Pond simply by using the overturned Shallow Pond as a lid, I largely left the Shelf Pond as-is, just empty. The plants that remained were certainly cold-hearty and perennial in my zone (3B to 4, depending on how you want to read it). Would they come back the next year?

The Shelf Pond is drained and awaits winter after what was probably just over a 3-month operational stint.

Temperature Management

It should come as no surprise that trying to heat and manage temperature in an outdoor aquarium of any type could present some unique challenges. Fortunately, here in Duluth, MN, overheating is probably not something I’ll ever have to worry about much. Instead, fighting the cold, often on a nightly basis, comes into play.

Generally speaking, my heaters were oversized for the given volume of water. I may have easily gone as high as 10 watts per gallon, which is far cry from the 5 watts per gallon I was raised on, and even higher than what seems to be a 2.5-watts-per-gallon rule of thumb that’s present nowadays. But consider that daily temps can easily swing 30F or more, and that, as fall approached, highs in the 50s or 60s were quickly the norm. 2.5 watts per gallon isn’t going to take the edge off plummeting nighttime water temps, and it simply would lack the pull-up ability to create suitable temps in the colder days/months.

Looking at my setups, I’ve considered that the area of air between the liner and the whiskey barrel must offer some level of insulation from heat loss, and I’m not sure how much insulation capability the wood offers. One of the things I’ve been thinking of is the possibility of using some sort of spray foam to fill in the area between the liner and the barrel to help with heat retention in these “tropical” ponds.

It’s impossible to say how, but I found that the heater on the shallow pond had cracked (a 100-watt submersible in a pond of 10 gallons). Considering that I’d seen this pond literally “steaming” on some colder mornings and days, it could be that the heater never turned off, but with no circulation in the pond, it basically overheated and cracked. Another possibility is that it was cracked by a rummaging forager.

Floating glass thermometers were unobtrusive yet useful for temperature readings in the container ponds.

Critter Problems

Rummaging foragers are certainly to blame for the number of floating glass thermometers I went through (at least 3). There are limited options for temperature readings in this outdoor scenario, and I found that floating glass seemed like a good option. It required no attachment, and could easily be picked up for a quick reading. Unfortunately, I routinely found them on the ground, sometimes broken. It’s a safe bet that some larger mammal (or bird?) was curious.

I cannot say how many of my losses were the result of predators. What was clear was that wildlife certainly was coming around the ponds with curiosity, and sometimes destructive results. While there was evidence that animals were getting onto the taller, full-size ponds (thermometers in them winding up on the ground), the shallow pond was the only one where I routinely found the actual decor of the tank out-of-sorts, strongly suggesting animal activity.

A Second Season to Come

I sit writing this recap of 2015’s container ponding season knowing that I’ve made some changes now in 2016. In the next installment, I’ll share how things overwintered, both indoors and out, and introduce you to this season’s ideas and projects!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks