In the year 1937, A. E. Robson of High Gate, London, England, introduced to United Kingdom (UK) members of the Guppy Breeder’s Society (GBS) a new strain which would become known among domestic Guppy breeders as the Robson Guppy.

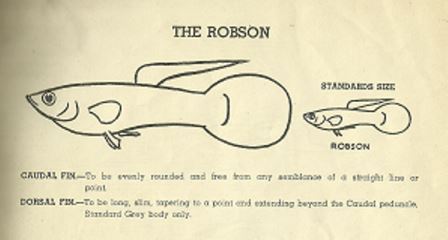

A strain produces a visible phenotype (a grouping of multiple traits). The Robson strain incorporated two unique traits in females at the time: first, the phenotypical structure of the dorsal resembled that of males from other early strains, still bred today, including the Speartail, while the caudal structure resembled that of the Roundtail, also still bred today. The primary noted difference with Roundtail was a long tapering dorsal with extension well into the caudal round, as compared to early and modern Roundtails, which possess a much shorter and rectangular dorsal that does not extend into the caudal round. The example below is a Robson-type male.

Second, and most importantly, the Robson females expressed color in their finnage. While this may seem inconsequential today, the Robson females are documented as being one of the first captive-bred strains to express either sex-link or autosomal-linked color in finnage (albeit black melanophores and not actual color pigment). The example below is a modern Black Moscow female with black finnage and extended non-tapering dorsal.

DESCRIPTION & HISTORY

At the time, scientific research involving Poecilia reticulata was still in its infancy. Most notable researchers at the time were O. J. Winge, L. J. Blacher, Johs. Schmidt, C. P. & E. F. Haskins, J. P. Druzba, V. F. & A. I. Natali, and V. S. Kirpichnikov, to name a few of the more notable, who were doing studies nearly exclusively on captive-bred, wild-caught populations. In wild-type, Mother Nature imposes many restrictions, which are best defined as “fitness traits” geared towards the survival of P. reticulata despite its role as a prey species. One of these is “color neutral/clear caudal” females. Above the lateral line, female coloration is specifically adapted for camouflage from above; below the lateral line, female coloration is adapted for camouflage from below. Minimal finnage appears clear to the naked eye and in the shape of a genetic roundtail.

The available published research at the time suggested wild-type females possessed little or no color pigment in genotype (XX-link), and thus passed little color or pattern genotype on to male offspring. However, when this information was disseminated to breeders by aquatic authors of the day, it mistakenly assumed that the results applied to wild-type results would also apply to domestic strains being developed. As A. E. Robson showed in 1937, this was not the case. His simple strain, by modern standards, proved that P. reticulata females were capable of expressing color in captive-bred domestic strains, extracted from traits existing unexpressed in wild-type. It would also help corroborate later research showing that females were:

1. Capable of naturally possessing color in genotype (XX-link and autosomal)

2. Capable of acquiring color through chromosomal crossover (Y- to X-link) during meiosis

3. Capable of androgen-based expression of color pigments.

By the early 1950’s, researchers were showing in captive bred wild-caught populations what breeders had demonstrated in their tanks 15 years prior. That is, in native high-predation locations, much of male color pattern was preserved and passed not by Y-link inheritance, but rather X-link and autosomal. Flashy Y-link males gain benefit via female sexual selection preference in both low- and high-predation locales. Yet, they suffer higher mortality in the latter. Therefore, it is not beneficial for males to pass high degrees of color/pattern and reflective qualities to all sons in the form of Y-link. The stage was set for development of the wide array of domestic Guppy strains we see worldwide today.

It would be nearly another 10 years before the GBS recognized the Robson phenotype in its breeding standards of 1947. According to Klee, Robson females exhibited “a large round jet-black tail and a black dorsal.” The remainder of body and finnage coloration in Robson females was described as being blue iridophore and yellow Metal Gold (Mg), commonly seen in wild-type, though possibly more pronounced. Males were described by Klee as “lacking the black spots characteristic of the common guppy of the time, but they did have their tails and dorsal fins edged in black.” It should be noted that more recent Robson-type males (tapering dorsal and round caudal) express diversity of type found in color and pattern of modern short-tail strains, while those of earlier breedings were likely limited to “wild-type,” “multi,” or “Vienna” body color and pattern. In the example below is a male of Robson finnage type (tapering dorsal and round caudal) edged in black with modern Saddleback color and pattern.

While breeder lore indicates that creation of the Robson strain involved the use of Cream (double recessive blond (b) + golden (g) females), Klee contradicted this belief, without substantiating, stating that Robson infused “imported females that exhibit much black in their fins” into his gene pool.

While Robson Guppies were to be found in continental Europe, their core support came from breeders in the United Kingdom. The UK Federation of Guppy Breeders Society (FGBS), successor to the GBS, standards defined the Robson in 1955 and 1961 as “Caudal Fin – to be evenly rounded and free from any resemblance of a straight line or point. Dorsal Fin – to be long, slim, tapering to a point and extending beyond the Caudal peduncle. Standard Grey body only.” This clearly defined Robson as a body style trait and not in regard to color or pattern. The FGBS was geared towards production of Short-tail Guppies.

In 1961, UK Fancy Guppy Association (FGA), successor to the FGBS, failed to recognize in its Standards Handbook the Robson Guppy as either a body type or color class. Instead, they listed “FEMALES, ALL VARIETIES, COLOURS” on fins should be varied and brilliant. Revised 1967 standards had apparently seen the error in previous interpretation of the Robson phenotype by re-classifying prior standards from that of a “body/finnage type” to a “basic body colour.” This stated, “Robson – Permitted only in the grey standard basic body colour. The dorsal and caudal fins must be black and no other colour on the body or fins is allowed.”

However, doing so set the course for continued declining interest and eventual demise of this 30-year-old phenotype. From foundation to demise, the FGA was founded and geared toward production of Broad-tail Guppies. By 1973, the Robson phenotype was no longer included in FGA standards for either color or body.

Asian Black Moscow female of Robson coloration, with tapering dorsal and minimal extension. Photo courtesy 曾皇傑 Tseng Huang Chieh

DISCUSSION & GENETICS

So, what brought about the demise of the Robson phenotype as a strain recognized by formal Guppy Breeder Associations? As late as 1989, The UK Federation of Northern Aquarium Societies, in its publication, “A Simple Guide to Identification; Guppy (Fin Shapes),” listed the Robson Guppy as a body type. The Robson was never formally recognized in North America by the American Guppy Association (AGA) or its successor, the International Fancy Guppy Association (IFGA). Nor was the Robson ever recognized in continental Europe by the Internationales Kuratorium Guppy Hochzucht (IKGH), active since 1981. From its creation in 1937 until the 1970’s, the Robson Guppy strain was primarily bred by breeders in the UK.

While the Robson Guppy created quite the stir in its heyday, it could not compete with changing breeder interests and new developments in their tanks. Interest during the 1950-60’s was shifting from Swordtails and Short-tails to colorful new Broadtail strains. A standard limiting females to black coloration in finnage and none in body did not help in bolstering dwindling interest. Trying to locate photos of the Robson is like hunting for a needle in a haystack. Few, if any, seem to have been photographed by breeders in tanks or at shows. None of these breeders are active today. To date, I have located only a single color plate indicative of a Robson male; see Madsen, J. M., (1975) Aquarium Fishes In Color. In the example below is a male of Robson finnage type (tapering dorsal and round caudal) with modern Full Red color and pattern.

Like most modern Domestic Guppy strains, the Robson was likely not the result of a “new mutation,” but rather the product of X-link, Y-link, and autosomal traits hidden in wild-type. More often than not, these traits are in simple non-linked combination passed by males and females, rather than a true linked complex that is passed to offspring in a single event. They are identified in captive-bred populations subject only to selection imposed by breeders and not natural predation or female sexual selection preferences imposed on wild populations. Large-scale mutations are rare and infrequent events, and are almost immeasurable. Small-scale mutations, on the other hand, are being recognized as frequent and commonplace. These occur on both the chromosomes and autosomes in the form of transpositions in small snippets of DNA. While producing new phenotypes, this may also foster instability seen in breeder results within fixed strains.

In the case of the Robson, it is primarily comprised of X-link and/or autosomal:

1. Concentration of black melanophores in finnage, and

2. Tapering dorsal structure with extension.

While modern breeders still commonly associated the term “Robson” with a tapering dorsal in females, it should be remembered for its greatest impact. That is, the first documented expression of color in females as a result of X-link and/or autosomal genotype. This knowledge has allowed for the creation of all expressed female color in modern Domestic Guppy strains. How much of this is a direct result of Robson females? In all likelihood, not that much. In domestic breeding situations, it is commonplace for similar phenotypes to arise in multiple locations, just as it is in the wild.

It is feasible that the Robson genotype for colored finnage in females was used to further develop new strains. If so, most likely candidates are early European black and purple Veiltails. The genetic foundation of these strains was initially developed in the 1950-60’s, using females with X-link and/or autosomal black melanophores in finnage. From these, later Black strains have been produced, as in the example, below, of Asian- and North American-bred females.

Asian Midnight Black Moscow Delta with non-tapering dorsal and extension. Photo courtesy Desmond Koh

Asian Black Moscow female of Robson coloration, with tapering dorsal and no extension. Photo courtesy Sun Lee

Breeders should always keep in mind that regulation of color and pattern is considered generally distinct between body and finnage. Regulation between caudal and dorsal is often distinct between strains, as is extension genetics, which allows for variation in lengths of finnage types through breeder selection.

Tapering dorsal is still very much commonplace in non-black, finned Domestic Guppy strains, to include: Lyretails, Swordtails, Speartails, Pintails, and even Roundtails. Standards worldwide frown on a Roundtail tail guppy with a tapering dorsal, yet this still serves a purpose, in that it further demonstrates that a tapering dorsal and finnage pigmentation was never in a linked complex in the Robson Guppy. It also shows that a tapering dorsal is not linked in complexity to caudal shape, as each can be passed independently of the other.

So, has the Robson Guppy truly disappeared from breeder tanks? As a strain defined by earlier standards, possibly. In contribution to current breedings, not likely, as all components are still found worldwide in many improved strains. Thus, with effort, it could potentially be re-constituted in original form with well-defined breedings.

© Alan S. Bias – June 15, 2016

Permission granted for nonprofit reproduction or duplication of photos and text in entirety with proper credit for learning purposes only.

NOTE: All photos by author or used with express permission of breeder/photographer.

CONTRIBUTORS: Stephen Elliot, Kettering, England.

REFERENCES:

FGA, (1961, 1967, 1973) Standards Handbooks, First Edition 1961, Revised 1967, Revised 1973.

FGBS, (1955, 1961) The Guppy Breeders’s Standards Handbook, Seventh Edition, Rev. Jan., 1955, Eighth Edition, Rev. Jan., 1961.

Frazer-Brunner, A. (1953) The Guppy, The Aquarist, Reprinted 1953.

Haskins, C.P. & Haskins E. F. (1951) The Inheritance of Certain Color Patterns in Wild Populations of Lebistes reticulatus in Trinidad.

Klee, Albert J., (2003) The Guppy 1859-1967, Finley Aquatic Books.

Madsen, J. M., (1975) Aquarium Fishes In Color, Macmillan Publishing, Co.

Stoye, F. H., (1934) Color Breeding of Guppies, The Aquarium, Vol. III, No. 2, June 1934, pgs 32-33.

The Federation of Northern Aquarium Societies, (1989), A Simple Guide to Identification; Guppy (Fin Shapes).

Thank you sir.

Amazing article.

I have 3 types of fins in my fish room and this is one that had shown up two years ago from some cross breedings.

It is hard to find information on it and this has helped me a lot. Thank you for posting this.