A young aquarium-fish collector with one of the many plecos native to the Xingu’s “big bend.” With the completion of Brazil’s controversial Belo Monte Dam, both the fishes and the people who rely on them for food and income are now endangered species.

Article & images by Michael J. Tuccinardi

Excerpt from AMAZONAS, May/June 2016

Xingu. The word itself conjures up the image of a remote and impossibly exotic locale, one of the last truly wild places left on the map. For aquarium enthusiasts worldwide, the mystique of the Río Xingu runs even deeper, as it is home to some of the most spectacular, outlandish, and poorly understood freshwater fishes on the planet. It is a massive canvas depicting evolution at work, a living laboratory for Darwin’s “endless forms most beautiful”—species isolated and diverging from their next of kin just a river or two away. It is also an ethnological treasure, home to 18 distinct indigenous peoples who have managed to retain much of their cultural identity and tradition, due largely to their isolation.

Yet to those who have been following the news, Río Xingu is ground zero for what has been called the worst environmental disaster in a generation—the highly controversial, widely reviled Belo Monte Dam. This infrastructure project, which has been in development since 1975, has been reported even in mainstream international news outlets, mainly due to the fact that its impacts will include catastrophic environmental and social costs for the entire Xingu River basin. Despite almost overwhelming criticism from scientists, sustained protests from local indigenous people who stand to be displaced by the dam, and a slew of judicial challenges in Brazil, the Belo Monte project has plodded onward through years of conflict-ridden construction. As the dam passed from an unbelievable ecological nightmare into an even more terrible reality, observers braced for the complete devastation of one of the wildest and most unique of the Amazon’s tributaries.

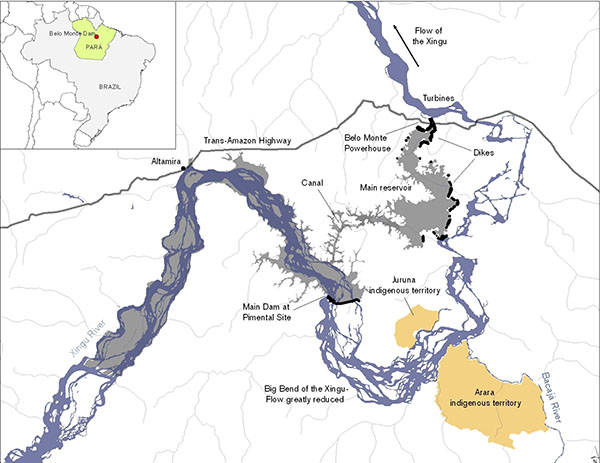

Map of Big Bend area showing the impact areas from construction of Belo Monte. Image: International Rivers.

The sordid history of the Belo Monte Dam, from its inception through the heavily contested and much interrupted construction process, has been documented in numerous news articles (as well as in the pages of this magazine), so I won’t spend too much time on the particulars here. Suffice it to say that the concept for the dam arose as a result of Brazil’s fast-paced development and the increasing demand for electricity that typically follows such growth. After years of planning, protests, revisions, and government intervention, construction finally began in earnest in 2011.

No Stopping Now

The project is owned by a consortium of state-owned utility companies known as Norte Energia and financed by over $10 billion from Brazil’s state development bank (BNDE), which is currently under investigation for a corruption scandal that has implicated the country’s president and prompted a major political crisis. Today, the dam stands completed, its floodgates raised, and despite some last-minute legal wrangling over its operational license, it will be up and running by the time this story is printed.

The dam is actually a complex of structures along what is known as Volta Grande—a big bend in the Xingu where the river takes a sudden 180-degree turn through nearly 87 miles (140 km) of rocky, generally shallow rapids. At Volta Grande, the main stream of the river spiderwebs outward into dozens of smaller channels separated by islands and shoals. This area is one of the epicenters of aquatic biodiversity in the Xingu and the one most impacted by the dam. The main dam is located about a third of the way into this big bend, just before the first major rapids. It reroutes the flow of water around Volta Grande and into a series of canals and reservoirs where pristine forests once stood. The flow is then directed into turbines far downriver at Belo Monte, completely circumventing its original path through the river’s big bend. It is estimated that this stretch of river will lose almost 80 percent of its normal water volume, causing a permanent, extreme low-water season at Volta Grande and essentially eliminating the annual flooding that most fish species rely on for feeding and spawning.

The main dam, just weeks away from being fully operational. This series of floodgates will divert up to 80 percent of the river’s flow away from the highly biodiverse stretch of rapids known as Volta Grande.

The project will leave vast stretches of once-submerged riverbed exposed—and, lest the environmental destruction caused by the dam remain incomplete, this land has been slated for intensive gold mining. A Canadian mining company, Belo Sun, has spent millions to obtain mining rights to land in Volta Grande just beyond the main dam, which is set to become Brazil’s largest open-pit gold mine. The environmental effects of gold mining on such a massive scale in the heart of the Xingu are hard to even imagine, but likely outcomes include increased deforestation, silting the river’s once-clear waters, and leaching of toxic slurry into the main river. It is difficult to conjure up a scenario in which the fragile and complex underwater ecosystems of the Xingu could survive this sustained onslaught. The Belo Sun mine, just like the dam, has faced significant legal challenges (including revocation of its license by a federal court in 2014), but progress on the project continues regardless. The company recently submitted a revised proposal to the Brazilian government, and analysts expect that the license will be reinstated in the near future.

Volta Grande, robbed of the flow of water that has sustained it for centuries, is not the only area of the Xingu to feel the effects of Belo Monte. The city of Altamira and many other areas upriver of the dam will see significant flooding as well. This has forced people out of their homes, causing unsustainable suburban sprawl outside the city, where rows and rows of tiny houses constructed by Norte Energia now stand. (The company is legally required to relocate residents displaced by the project.) In areas expected to flood, the local government has granted logging concessions, allowing clearcutting of forest to prevent trees and vegetation from washing downriver and clogging the dam’s spillways. It is a poorly kept secret that the logging companies have continued to clear areas well beyond even generous estimates of the flood zone. The dam will also significantly slow the flow of the river, turning areas of shallow, fast-moving water frequented by many of the Xingu’s endemics into still pools.

Xingu untamed: a last glimpse

Like many others, I have been following this story for years with a sense of dread and vague disbelief, along with a sort of “issue fatigue” that is becoming increasingly common among those concerned with the future of Earth’s fragile ecosystems. With the constant stream of bad news pouring in, it’s hard not to become numbed to individual issues like Belo Monte—especially when nothing can be done to stop it. But when my travels took me into eastern Brazil for a short time, I felt an overwhelming urge to see the thing itself, in the flesh, and to catch a glimpse—possibly the last—of the mighty Xingu before Belo Monte becomes fully operational. So, carrying little more than a backpack and the name of a contact who (I hoped) would meet me at the airport, I boarded a flight to Altamira, the only major city along the Xingu and the main staging point for the construction of the dam.

Flying into Altamira on a small, crowded plane didn’t afford much of a view, and with the cloud cover I had little hope of seeing much, but just as the plane began descending I was treated to a brief glimpse of the area through a break in the clouds—my first view of the Xingu and the entirety of Volta Grande south of Altamira. It was a breathtaking vista, but one marred by the crisscross of bright red lines where the soil had been exposed, like fresh, bleeding gashes in the earth. Soon I was walking across the Altamira airstrip to begin my journey to the dam. My first stop was a local aquarium-fish holding facility in town, one of several small enterprises in Altamira where fishes collected throughout the middle Xingu are brought and held for shipment to the export hub of Belem, at the mouth of the Amazon. Even though I had visited dozens of these little setups in the course of my travels in the Amazon, my eyes widened as I walked past rows of shallow plastic tubs, each filled with a stunning array of the colorful (and expensive) L-number plecos the region is known for. This facility was set on one of the main roads in town, overlooking the river, and from the door you could see the first unmistakable signs of the ecological havoc being wrought by the dam.

A view of Altamira from above, showing the burned and partially flooded island Ilha do Arapujá, one of the first casualties of the dam.

Island’s Charred Remains

Just across the river lay the charred remains of Ilha do Arapujá. Once a lush, forested island, home to two species of killifish found nowhere else on Earth, this strip of land now resembles a post-apocalyptic wasteland or a napalm-cleared combat zone. The island had been cleared and burned in preparation for the inevitable rise in water level after the floodgates closed on the dam. The sight of that ruined land brought on the first twinge of the horrible truth I was about to confront—this wasn’t just something I saw on the news, this was really happening. In stilted Portuguese, I talked to the owner and caretaker of the little fish house about the dam—what it meant for the business and what the future held. I expected a diatribe about the dam, but what I heard was vague uncertainty. The owner said he was looking to sell his house in Altamira and possibly find work elsewhere, but for now he wanted to keep operating his facility. The caretaker explained that although fishes had been scarcer lately, he hoped it would not get much worse.

My next step was to arrange for travel up the river to the Xingu’s big bend, Volta Grande—never an easy task—to visit aquarium-fish collecting villages there and see for myself what stood to be lost. The aquarium-fish seller in town helped me organize a boat and driver and put me in touch with a local fisherman, who traveled upriver regularly to collect and would act as my guide. With everything tentatively arranged for the following day, I didn’t want to waste the afternoon, so I enlisted the boat driver to take me out on the river, in the opposite direction of the dam, for some exploring.

The Xingu near Altamira is broad, crystal-clear, and surprisingly shallow—despite being an hour’s boat ride out and far from either shore, most areas were between 3 and 10 feet (1–3 m) deep. And although everything I had read about the Río Xingu should have prepared me for it, this is a fast river. The water flows over the rocky substrate with a force that’s hard to imagine until you’re in it and struggling to stand up in the powerful current. After some effort, I was able to improvise a method of exploring the river with mask and snorkel, using large rocks as anchors and pulling myself forward against the current. Beneath its benign surface, the Xingu conceals a bizarre and otherworldly environment—which has almost certainly influenced the evolution of the river’s equally unique aquatic life. The reddish, clay-like river bottom is largely covered with a wide variety of rocks—from small, water-worn pebbles to massive boulders.

Although at first this strange underwater landscape appeared rather barren, many of the river’s inhabitants eventually revealed themselves. Slender and impossibly fast Teleocichla darted around in small groups, occasionally venturing close in hopes of picking off small invertebrates from under the rocks I had disturbed. Even more wary were the beautiful Retroculus xinguensis, relatives of the eartheaters that are well adapted to the Xingu’s rapid current. Leporinus julii, very attractive spotted characins, also flitted by in small groups, using their torpedo-like body shape to swim effortlessly through the rapids. And of course, by carefully overturning some rocks I found an abundance of plecos—perhaps the predominant group of fishes in the Xingu.

The facility of one of the aquarium-fish traders in Altamira. Fishes from the middle Xingu are brought here before being shipped to Belem and then exported.

To Volta Grande: the Huge Bend

The next day, according to the plans I had made with the boat driver and the fisherman/guide, I made my way to Altamira’s waterfront in the early morning to begin the trek upriver to Volta Grande. Having arranged this sort of thing many times before, I anticipated plenty of waiting around for who knows what to occur before we actually got underway. I was pleasantly surprised when the boat driver arrived only 30 minutes late, but things soon took a frustrating—if predictable—turn for the worse when the fisherman did not show up and didn’t answer his phone. After almost three hours of fruitless waiting, unanswered phone calls, and driving up and down the waterfront, the disheveled-looking fisherman arrived and started conversing with the boat driver. I had been counting the passing minutes with increasing concern, as my return flight to Belem left later that night; there was no chance for a do-over here if the arrangements fell through.

My hopes were dashed even further when the driver returned to the boat sans guide and started the engine, and we began to head upstream without him. I seethed quietly with the realization that our carefully arranged plans—and the considerable amount of money I had spent to make them—had been for nothing. As we steered toward a mass of storm clouds on the darkening horizon, I tried desperately to think of a way to prevent this from becoming the most expensive and fruitless boat tour of my life. The boat driver, who was pleasant and helpful enough, didn’t know a thing about aquarium fishes, but said he would try to visit some villages where collecting occurs. Several hours behind schedule and guideless, I braced for the coming rain and hoped that the day would turn around.

After some time on the boat, the bad weather passed and some telltale signs of development began to emerge on shore. Deforested hillsides, recently cleared dirt roads, and a few logging camps passed by like mile markers, warning of our proximity to the dam. Wisps of smoke from a few lingering fires billowed upward to join with the last remaining grey clouds, and in the distance I spotted the first manmade structure I had seen since leaving Altamira. It was a large concrete ramp, buttressed with gravel and surrounded by shockingly red piles of earth. As our boat approached the ramp, a group of uniformed Norte Energia staff came sauntering down the hillside to meet us. Following the driver’s lead, I left the boat and got in a waiting Volkswagen bus emblazoned with the Belo Monte logo. Much to my surprise, a tractor towing a boat trailer backed down the ramp and lifted our boat clear out of the water, then followed the van along a recently paved road in what seemed to be the middle of nowhere.

What madness is this?

We disembarked after a short ride and our boat was placed back in the water at a small launch just like the one we had left. I was a bit dazed by this unexpected turn of events, so it took me too long to realize what had just occurred: we had been driven around the site of the dam. The dam had, of course, made the river unnavigable by boat, so our boat had to be hauled to the other side with heavy machinery. “Que loucura é essa?” (“What madness is this?”) I muttered to myself in Portuguese as I boarded the boat once again. The driver, seeming to understand, nodded solemnly and we continued on. As we rejoined the main river, abutted by a massive mound of red earth, I suddenly saw it—a low series of concrete ramparts on the horizon. As the boat drew closer I could make out the floodgates of the main dam, already diverting water into the sizable spillway feeding into the main turbines some 19 miles (30 km) away. To our right a power station sporting rows of transformers was emitting a high-frequency hum, the only sound audible over the idling outboard.

The main dam, just weeks away from being fully operational. This series of floodgates will divert up to 80 percent of the river’s flow away from the highly biodiverse stretch of rapids known as Volta Grande.

So this was Belo Monte. Occupying what is arguably the most fought-over stretch of the Amazon basin since the rubber boom of the nineteenth century, the freshly constructed dam, with its floodgates raised and just weeks away from being fully operational, was a somewhat disappointing sight. Put simply, it just didn’t look like much; it was difficult to imagine that this concrete obstruction could possibly have an impact on a waterway as vast and powerful as the Río Xingu. I realized, of course, that what I had seen was just a small part of the overall dam complex—the metaphorical tip of the iceberg—and that from a better vantage point the damage and deforestation would seem exponentially greater. But as the dam quickly faded from view and we entered Volta Grande itself, the impact of this incongruous feat of modern engineering deep in the Amazon basin became immediately apparent.

Rounding a sharp bend in the river, we entered a series of rapids and cascades that the boat driver navigated handily. Once we were through, he looked concerned, stating that the water should be much higher by now. With the dam nearly operational, this stretch of the river was unlikely to ever see a high-water season again. The “big bend” region of the Xingu is strikingly beautiful, a tropical oasis of forested hillsides and rocky shores—but the freshly exposed rock formations in the middle of the river and the long sandbars were proof that the water flow to this entire area had been permanently altered. Here, in Volta Grande, is where many of the popular aquarium species from the Xingu are collected, and despite the morning’s setbacks I still held out hope for visiting with fishers in the communities downstream.

Pleco Hotspots

The first of these communities that we reached was a tiny settlement known as Ouro Verde (green gold), a cluster of small wooden houses abutting a red clay beach. The boat driver thought there may be some aquarium fishermen in this village, although that turned out to be incorrect—the primary livelihoods here were mining and mineral extraction. A ways downriver, we came across another, slightly larger village, Ilha da Fazenda, which was known in the region as a major center for aquarium-fish collecting. After wandering through the town, we met an older man who had collected ornamental fishes here for many years. Now, however, he was retired. His son had landed a job working for Belo Monte downriver in Vitoria do Xingu, and he proudly showed me a large map of the dam complex hanging in the living room of his small wooden house. When I offered to hire him as a guide for the next few hours, he politely but firmly declined. Another half-hour of inquiries around town turned up nothing—locals either didn’t know any aquarium fishers in town or told us they were away at the moment.

Inside an aquarium-fish holding facility, the caretaker proudly shows off a Scarlet Cactus Pleco (L025).

Somewhat defeated, we left Ilha da Fazenda and continued further into Volta Grande. The boat driver, trying his best to be helpful, offered to take me to a shallow area where I could find peixes ornamentais—ornamental fishes. Along the way we passed by two large indigenous territories, Paquicamba and Arara, both of which had resisted the construction of the dam for years. They appeared largely deserted—some of the residents had probably retreated back into the forests, and others, no doubt, had migrated to Altamira looking for work and shelter. We made our way among the rocks with some difficulty, the river here being in a permanent dry season due to the dam. Eventually the boat turned into a small, extremely shallow branch of the main river, strewn with boulders.

Here I spent a good hour exploring the river and saw plenty of pleco species familiar to most hobbyists. Gold Nugget Plecos were almost always encountered in horizontal cracks in the boulders, where they live in close association with Medusa Plecos (Ancistrus ranunculus, L034). This may represent a symbiotic or commensal relationship between species and warrants further investigation. The massive Goldie Pleco (Scobinancistrus aureatus, L014) was also common in this area, although they moved far too quickly among the rocks for my clumsy attempts to collect them. Large pike cichlids, Teleocichla, and Leporinus julii were also abundant, darting quickly away whenever I approached too closely. It was an incredible ecosystem, unique among all the rivers, streams, and flooded forests I had visited in the Amazon basin thus far. But as the sun moved ever closer to the western horizon, I was reminded that my goal in coming to Volta Grande remained unaccomplished. After conferring with the boat driver once more, it was decided that we would return to Ilha da Fazenda and make a renewed effort to find some aquarium fishers who would, ideally, spend the rest of the day with us (a not-insignificant amount of money would be necessary to help make this possible).

As we pulled up onto the beach in front of the small village for the second time, we were greeted with some fantastic news: a group of local fishermen had just returned from a morning collecting trip with a boatful of aquarium fishes. We hustled over to where their canoe was moored and struck up a conversation as they began sorting their catch. The fishers were two brothers—the younger one, Daniel, a boy of no more than 10—and an older cousin, João, who owned the boat. Aquarium-fish collecting had been their family’s primary trade for many years, and as I watched them working their collective experience in this trade was obvious. They had arrived with just over 280 small Gold Nugget Plecos (Baryancistrus xanthellus, L081) in several stacked plastic tubs. Water changes were carefully performed on each tub and the fish were hand-sorted by size. From there, they were transferred to simple plastic holding pens that were placed in the river. These contained a large amount of rockwork, both to weigh them down and to provide ample cover for the plecos held within.

The fishers were planning on heading back out almost immediately to collect some different pleco varieties in a different area, and after some persuasion (of the monetary variety), we were able to go back out with them and observe them working. I was fairly buzzing with excitement at this unexpected turn of events as we motored toward the exact same spot I had been exploring earlier.

I struck up some simple conversation with the fish collectors. They worked freelance, usually collecting for the same Altamira shipper I had visited. They collected fishes two or three days per week and made a weekly boat trip upriver to Altamira to deliver them. At the moment, there was a lot of demand for Gold Nugget Plecos, which were among the easier fishes to collect. João occasionally used the hookah method, in which the fisherman holds in his mouth a long plastic tube connected to a compressor aboard the boat, to dive for some of the deep-dwelling plecos—including the endangered Zebra Pleco (Hypancistrus zebra, L046), which, although banned from export by IBAMA, still makes its way into the trade regularly by way of Colombia and Peru. I learned that aquarium fishing is a year-round occupation for many in Ilha da Fazenda, with more than six extended families in town relying on this trade for their primary livelihoods.

Plecos like these two are collected from the rocky Xingu largely by hand.

No-Net Fishing

When we arrived back at the shallow rocky area, the fishers disembarked and immediately began fishing. Using well-worn dive masks and a simple wooden tool, they quickly brought up dozens of plecos at a time, holding the smaller fishes in their mouths (!) or using modified plastic Sprite bottles to contain larger ones. It was remarkable to witness the ease with which they were capturing fish after fish—even Daniel was deftly collecting plecos by hand in waist-high water—from the same spot where earlier I had struggled for the better part of an hour to collect anything. The skill level and the ecological knowledge these fishers displayed was remarkable—as they brought up each pleco species, they would tell me its local name and its preferred habitat: horizontal crevices, vertical crevices, rounded caves, near patches of freshwater sponge, and so on.

In between rounds of diving we talked about the business, their outlook on the future, and their feelings about the dam. They explained that the construction of the dam had been very bad for fishing—that many fishes had died due to poisoning or from the blasting used during the early stages of the project. This year, however, was a good year for the fishes—although the water was very low for food fishing, conditions had been ideal for collecting plecos. Furthermore, they were quick to explain that Norte Energia had helped their village significantly, having installed its first sewer system and providing much more consistent electricity. There was ambivalence about some things, especially that the lure of paying jobs had driven many of the young people in the community away to Altamira or Vitoria, but the conversation was a reminder that Belo Monte had done a masterful job of gaining local support through federally mandated infrastructure projects and slick public relations.

When I asked about the dam’s impact on the fishes, João said that they had been assured by Norte Energia representatives that there would be little to no effect on Volta Grande from the dam, and he took the current boom in aquarium-fish collecting as a sign that the worst was over. Eduardo, the older brother, was not so sure, pointing out the low water levels and expressing concern about the increased mining and mineral extraction activity in the area. He had heard that Volta Grande was going to be mined for gold, and he was under no illusion about its effects on the river. “The mining, the chemicals, they kill all fishes. They destroy the river. And now with the dam the fishes cannot return.”

We discussed what they would do if they could no longer collect aquarium fishes here, and they expressed a somewhat fatalistic attitude toward an uncertain future. João’s brother-in-law had moved to Altamira, where he worked as a private security guard, and João anticipated doing the same if the fishing dried up. Eduardo hoped to stay in Ilha da Fazenda, but understood that that meant limited options for work. It was not the easiest of conversations, given the language barrier, and I let them get on with the rest of their work as they finished collecting some of the varieties their buyer in Altamira had asked for. These included Medusa Plecos (Ancistrus ranunculus, L034), Spectracanthicus punctatissimus, and the very pretty Jaguar Pleco (bolo onça in Portuguese), more commonly known as the Golden Vampire Pleco (Leporacanthicus heterodon). João and Eduardo were obviously in their element below the water’s surface, doing something they had both learned as kids and instructing Daniel—the next generation—on the most effective methods.

This was difficult to watch, knowing that this skilled work, which has sustained so many families along the Xingu for years now, would soon be a relic. As the ecosystem collapses, aquarium fishers will be the first to feel the effects. Over time, people in fishing villages like Ilha da Fazenda will be forced to make the difficult choice between leaving in hopes of a better life elsewhere or remaining and eking out an increasingly challenging existence in what was once a thriving corner of Amazonia.

A short time later we returned to Ilha da Fazenda to drop off the three fishers and their catch, an impressive haul of about 60 fishes. These fishes, and the Gold Nugget Plecos they had collected earlier that morning, would be sent to Altamira in a few days and from there would make their way to exporters in Belem before being shipped out to the United States, Europe, Hong Kong, or Japan.

Boomtown before the bust

In town, I accompanied the boat driver to a house where he purchased some dinner for the evening—two pacu, the endangered Ossubtus xinguense, and a string of frozen plecos (likely Parancistrus nudiventris, L031). We stopped for a celebratory shot of conhaque, a kind of syrupy local liquor, on the way back to the boat and began the long journey back upriver to Altamira. The return trip passed uneventfully, but with clear skies this time around I was able to see more evidence of the dam’s impact on this once-pristine stretch of river. Deforested hillsides, with logs lined up awaiting pickup along the shore, bore testament to the increased logging activity in the region. In the rapids, rusted-out remnants of industrial equipment protruded above the water’s surface where they had gotten snagged among the rocks. Finally, the dam appeared in view once again, its angular superstructure marring the horizon. After another trip around the dam, courtesy of Norte Energia and Belo Monte, I watched fishes through crystal-clear water at the edge of the newly built pier as I waited for the boat to be put back into the water. The mummified remains of a dead Xingu River Ray (Potamotrygon leopoldi) gathered flies among piles of branches and debris that had washed up on shore, a visceral reminder of the dam directly behind me.

Pleco hunting in action: Daniel, a young aquarium fisher in training, collects Gold Nugget Plecos from the shallows.

Back in Altamira, having nothing left to do but kill time before my flight out, I sat on a bench beside the main road out of town and overlooking the waterfront. It was almost evening now, and in a frenzy of activity, Belo Monte workers were returning home from their day’s work on company-owned buses. Over the course of an hour, more than 30 Norte Energia buses—each full of workers—blew past me in a cloud of diesel exhaust, leaving me to reflect on the fleeting nature of Altamira’s prosperity and the incredibly short-term thinking that had led to the dam. In a year, almost all of those jobs will disappear as construction wraps up. Altamira will begin the age-old slide into a boomtown gone bust. The thousands of people who have migrated toward the city to work will be forced to move to yet another city to hunt for employment or return to small communities in and around the surrounding forests, where the influx of people will fuel a rise in logging and slash-and-burn subsistence agriculture. Some will almost certainly find work in Belo Sun’s vast new mine at what was once Volta Grande, where they will extract what mineral wealth they can for a few years before moving on, having thoroughly poisoned what remained of the Río Xingu’s big bend.

Now that I have finally seen the Xingu for myself, possibly for the last time before the dam irrevocably reshapes the river and forces dozens of its endemic species into decline and extinction, it is hard not to mourn the loss of one of the most important and legendary waterways left on Earth. It is truly one of the more wild places I have ever seen and experienced—an ecological paradise whose uniqueness and isolation have combined to form wilderness and aquatic habitat unlike those found anywhere else on the planet. Still, I count myself fortunate to have caught a glimpse of the Río Xingu “monstrous and free” before its now-inevitable demise.

In Altamira, however, I was confronted with the enormous human cost of the dam as well—forced resettlement, unfulfilled promises of prosperity, whole families and entire ways of life uprooted and removed in the name of progress. It is a story that has played out too many times in recent history, and but for the relentless myopia of the human race when money and power are in play, we would have learned our lesson long ago.

It is unlikely that, a decade from now, the Belo Monte Dam project will be viewed as anything but a monument to institutionalized greed and poor planning. Perhaps, by then, the harsh lessons learned and the irreversible damage done will prevent other tragedies on this scale from playing out in other parts of the world where dams are being erected, but that remains to be seen.

Resources for Belo Monte info:

http://amazonwatch.org/work/belo-monte-dam

http://www.internationalrivers.org/campaigns/belo-monte-dam

www.economist.com/news/americas/21577073-having-spent-heavily-make-worlds-third-biggest-hydroelectric-project-greener-brazil

www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/dec/16/belo-monte-brazil-tribes-living-in-shadow-megadam

http://norteenergiasa.com.br/site/ingles/belo-monte/

http://www.theecologist.org/News/news_analysis/1016666/belo_monte_dam_marks_a_troubling_new_era_in_brazils_attitude_to_its_rainforest.html

www.fluvalaquatics.com/ca/explore/expeditions/xinguexpedition/#.VttSStCm1TM

AMAZONAS Subscription

Don’t miss an issue of the world’s leading freshwater-only aquarium magazine.

SUBSCRIBE

BUY THIS ISSUE

Good article Mike, this disaster need to be raised frequently and I’m glad I was one of them that started the debate what is really happening in the most beautiful places of Amazonas and the plans of large scale dam constructions for many years ago. If people continue the same we may prevent even more disasters in other rivers of the Amazon.

Cheers

The dam never should have been built!