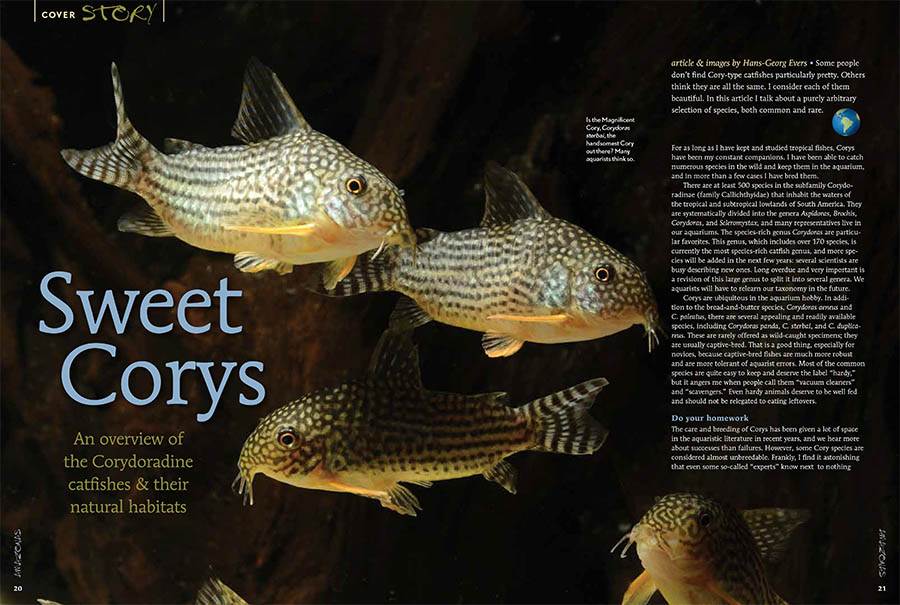

Opening spread to almost two dozen pages of cover features section devoted to Corydoras Species & Habitats, with an introduction by Cory expert and AMAZONAS German Editor Hans-Georg Evers.

A partial excerpt from “Sweet Corys,” photos and text by Hans-Georg Evers, published in the November/December 2015 issue of AMAZONAS Magazine

Rio Araguaia

To me, just the name of this river is magical. In the past I did some very successful tours around the middle Rio Araguaia. Back then, families could live quite well by collecting aquarium fishes in the state of Goiás, but for several years now fishing for aquarium fishes has been completely prohibited in this Brazilian state, and all the former collectors have turned to other lines of work.

The little town of Aruanã on the middle Rio Araguaia was our starting point. From there we explored the diverse waters in the Araguaia basin and further north in the catchment of the Rio Tocantins. We collected no fewer than eight different Cory species in the middle Araguaia and its large tributary, the Rio das Mortes. Six of them have very similar patterns: rows of black spots on a white to nearly orange base color.

The most frequently encountered species was the pretty Corydoras araguaiaensis. This species, about 2.4 inches (6 cm) long, can be found in many rivers, from white water to clear water, and tolerates extreme conditions in the dry season. It survives in the remaining puddles of water and waits for the onset of heavy rain in November.

At the end of June, in a pool of water measuring about 10 x 30 feet (3 x 9 m) with a maximum depth of about 1 foot (30 cm), a pH of 6.5, and a temperature of 87.8°F (31°C), we caught over 1,000 Corydoras araguaiaensis, C. sp. C122, and Brochis splendens. Although the water was at its lowest, all were very healthy and strong. During another trip in March we fished in the same location (pH 6.0, 82°F/28°C) and could hardly catch anything—and the water was about 8 feet (2.5 m) higher than it was in June!

In the Araguaia, as well, Corys respond to the onset of high water and begin spawning in November or December. In March we collected nearly half-matured juveniles that had been spawned in those months. Even the best aquarist cannot achieve such rapid growth in the aquarium. If you would like to breed Corydoras araguaiaensis—there is still broodstock available in the hobby—keep the aforementioned periods in mind. Given plenty of food, frequent large water changes, and the use of a flow pump in November or December, the fish should be willing to spawn.

In the Rio Cristalino, a tributary of the Rio das Mortes, both the large spotted C45 and C68 can be found. In March, using headlamps in the dead of night, we collected the animals with a dip net in the shallow water (8 µS/cm, pH 5.5, 84°/29°C) along the sandy banks of the Rio Cristalino. Moonless nights are ideal, because the fishes do not see you coming, but you must tread very carefully to avoid the many stingrays. During many excursions in South America, I have noticed that Corys sometimes seek safety by resting in large numbers on the sandbars at night. At dawn they move to deeper water to avoid being eaten by birds.

In a group of 10 C45, there was usually just one C68. Corydoras sp. C68 is a very rare species and is not even represented in the collections of Brazilian museums (L. Tencatt, pers. comm.). We found only adult animals of the two species; they were a maximum of 3.2 inches (8 cm) in total length.

We had to change the water in the collecting bucket every few minutes, as it started to foam. When threatened, many Corys emit a toxin via the axillary glands at the bases of the pectoral fins. The phenomenon is particularly well known in adult Corydoras sterbai. One often hears from aquarists that their adult fish did not survive shipping and that the shipping water was very cloudy; this is less likely with juveniles. The only way to avoid it is to keep the fish in a holding tub or bucket before shipping them and change the water several times before they get bagged. Especially the spotted species appear to be very sensitive, especially C. sterbai, C. araguaiaensis & Co., and C. gossei. Exporters usually capture the animals the evening before shipping them out and put them in shallow pans. They change the water repeatedly until it stays clear, then pack the fish for shipping the next morning.

My favorite Cory

After I had been on the Araguaia for a few weeks my host, Valerio Paulo da Silva, honored me by showing me the secret location of a beautiful species that his father, Savio, had discovered many years before. The species lives in a small igarapé in the catchment of the Rio Araguaia, where the clear water (8 µS/cm, 83°F/28.5°C) flows over a sand bed. The fish keep primarily the edges of the shallow stream, below the protective embankment.

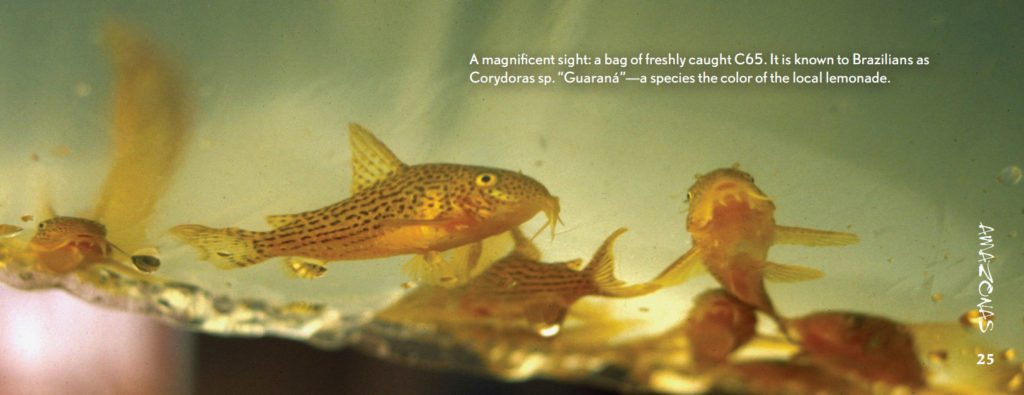

Since the population is very small and they do not want to overfish, the family has collected in this locality only a few times. In March of 1998 we collected 30 specimens of this undescribed species, which the Brazilians call Corydoras sp. “Guaraná” after a popular caffeinated soft drink that is the same reddish-orange color. I preserved several animals for scientific purposes and sent them to a museum. Later I sold several more fish in England and took 10 home. Since that time I have been breeding the species, which I later designated with the code number C65, and it is my absolute favorite Cory.

[Editor’s Note: Corydoras sp. C65, also known as Corydoras sp. “Guarana”, has now been described as Corydoras eversi Tencatt & Britto, 2016.]

A magnificent sight: a bag of freshly caught C65. It is known to Brazilians as Corydoras sp. “Guaraná”—a species the color of the local lemonade.

In 2003, while giving a lecture in England, I mentioned the C65. My friend Ian Fuller jumped up and exclaimed excitedly that he was the one who had purchased the original exported fish. All the animals in the hobby can be traced back to the specimens we collected in 1998. I still breed the species, now in its sixth generation, and guard them with my life.

Much More To See

Get the full article and learn more about species like Corydoras gossei, C. seussi, C. haraldschultzi, C. sterbai, C. noelkempffi, C. guapore, C. panda, C. pinheiroi, and Scleromystax barbatus, when you purchase the November/December 2015 issue of AMAZONAS Magazine.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks