Asian Red Arowana, Scleropages formosus, a fish with ancient origins but endangered by habitat destruction in its native waters.

It takes precious little imagination to envision arowana lurking in the same prehistoric swamps where the dinosaurs grazed, and now research from Malaysia is confirming that members of the family Osteoglossidae may be among the most primitive fishes surviving today.

A research group from Monash University Malaysia has successfully sequenced the genome of a prized aquarium fish from the home waters of Malaysia: the Asian Arowana. This is the first Malaysian fish genome to be sequenced and the first achieved by a Malaysian university. The Asian Arowana is a high-profile Southeast-Asian freshwater fish that’s highly coveted within the Chinese community as an ornamental species for its brilliant gold and red scales, a symbol of prosperity.

The Asian Arowana has been highly endangered in the wild since the 1980s due to habitat destruction and over-fishing. Also known as the “Dragonfish” for its twin whiskers, metallic scales, and long, sleek body, the arowana can fetch up to thousands of U.S. dollars in a market where international law tightly restricts its sale. The Asian Arowana has been listed as endangered since 2006 by the IUCN Red List, and is protected in the U.S. by a listing under the Endangered Species Act. This species can be kept legally only with a special permit.

But beyond its commercial value, the Asian Arowana (Scleropages formosus) is of considerable academic interest, too.

According to Prof. Christopher M. Austin, Genomics Cluster Leader at the School of Science, “The arowana belongs to a very old group of fish which you could refer to as ‘living fossils.’ One of the things we’re interested in is: Where does it fit in the family tree of fishes? Our study actually contradicts some views on the fish family tree.”

How exactly can scientists trace an animal’s rightful place in the family tree?

“Every species carries its genealogical history in its DNA,” says Prof. Austin and his team. “Using genetic sequencing and bioinformatics methods, we can actually reconstruct the path of the evolution with considerable accuracy.”

The arowana’s relationship to other fish species is determined by comparing a large number of genes recovered from its genome sequences to the same genes from other fish species that have also had their genomes sequenced.

Every new genome that’s published, therefore, helps all kinds of other genetic and genomic studies. As Prof. Austin puts it, “The arowana genome is not just a genetic resource for us. It’s also a resource for anybody studying comparative biology of fish.”

Asian Arowana with a green cast, one of many hues seen in this species, including gold, blue, yellow, and many shades of red, and silver (not to be confused with the South American Silver Arowana, Osteoglossum bicirrhosum.)

Most primitive: the eels group or the arowana group?

“Our study indicates that arowana is the most primitive of the modern fishes,” Prof. Austin says. “The evolutionary position of the arowana has been disputed in scientific literature—whether it’s the arowana group or the eel group that’s the most primitive form. Some recent publications suggested eels, but our publication suggests the arowana, which agrees with the more traditional scientific studies.

“Its appearance has not changed much over a very long period of geological time, and we’re talking millions and millions of years. But just because you’re primitive doesn’t mean you’re obsolete.” He also cautions, “We can’t entirely say that the arowana is an all-round primitive fish because it’s not. The fact that it produces a small number of big eggs and that the males take care of the eggs is actually sort of more modern, if you like.”

He likens arowanas to sharks, another fish that’s full of primitive characteristics but has survived millions of years. “When we started, only about 20 fish genomes had been published in the world, which is a small number compared to mammals and birds,” he says.

Apart from sequencing the first Malaysian fish genome, says Prof. Austin, “This is also the first time a Malaysian-led research group has sequenced a fish genome, which demonstrates that with recent improvement in DNA sequencing technology you no longer need a large multinational team and millions of dollars to sequence the genomes of important plants and animals.” The arowana study was a productive partnership between Malaysian and Australian experts.

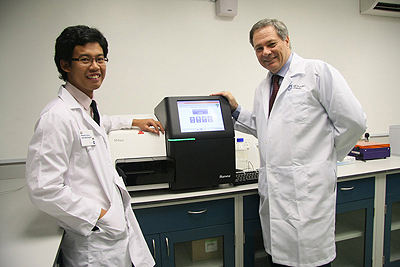

Dr. Gan Han Ming with Prof. Chris Austin with one of two new Monash University of two state-of-the-art DNA sequencing systems that will open the doors to studying many other Malaysian fish species.

The study, recently published by the Oxford journal Genome Biology and Evolution, was co-authored by Prof. Austin and Mun Hua Tan, a bioinformatician at the Genomics Facility, along with Dr. Han Ming Gan (corresponding author, research fellow and laboratory manager), Prof. Larry J. Croft (Malaysian Genomics Resources Center) and Michael Hammer (Museum & Art Gallery of the Northern Territory in Darwin, Australia).

The team hopes their work will contribute not only to evolutionary research but also to wildlife conservation in Malaysia. The arowana, they say, could serve as a touchstone to draw Malaysians’ attention to local freshwater systems, which are often threatened by manmade change.

Meanwhile, arowana research is also valuable to commercial fish farmers. These genomic resources aid understanding of the arowana’s physiology and how genes are expressed and have applications for selective breeding.

For example, the Monash team has identified 90 genes in the arowana genome that may influence its color. If studied further, this could be very helpful to fish farmers, who currently breed arowana through traditional breeding, which can be inefficient and lead to inbreeding if not done carefully. Besides being able to identify and study genes that determine color, a simple genetic test to identify sex (which is very difficult in arowana based on morphology) would be very useful. Finding genes that influence growth and survival would also be of interest to commercial farmers.

Highly prized as an aquarium fish (in Chinese lore it brings good luck, success, and longevity), the Asian Arowana is considered a huge opportunity for fish farmers.

Prof. Austin sees that the next step for their research will involve working with arowana breeders and farmers. Together, they could improve the quality of arowana stocks through genetically-enabled breeding programs which would involve genetic testing in the lab and on-farm trials.

Working with farmers could also benefit research and conservation. It’s possible that farmers may own arowana stocks which originated from wild populations that are now extinct, thereby preserving important elements of arowana genetic diversity that have since been lost outside farms. Such stocks could potentially be a source for the reestablishment of wild populations.

The Monash team hopes its research will be an important platform for future research collaboration with commercial farmers, conservationists, and other researchers interested in this iconic Malaysian fish species.

The published arowana genome is now public. It can be found online at GenBank, a database of the U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information. The article is available online at http://gbe.oxfordjournals.org/content/7/10/2885.full

SOURCES

From materials released 16 December 2015 by Monash University Malaysia. First Malaysian fish genome sequenced.

Wikipedia: Asian Arowana.

Image: Asian Red Arowana, top: Shutterstock/SOMMAI

Image: Asian Arowana (green): Shutterstock/rprongjai

Image: Asian Arowana with Chinese words: Shutterstock/AppStock

I wish I can obtain a copy of this wonderful genomic study done on the Golden Asian Arowana. This fish is the envy of many Chinese families, as it represents wealth, prosperity and longevity. Moving majestically through the water, its scales exude a brilliant rendition of metallic colors as if taken from an artist’s easel. There are no fish who closely represent this awesome fish in existence, naturally, that is a matter of preference.

Amazonas brings the splendid inhabitants from the rivers, tributaries and estuaries to your home, where a wealth of knowledge on several fish is rolled out for your sheer enjoyment. No other magazine comes close as a rival to Amazonas. It is an exotic treasure to anyone who subscribes to this high- end magazine. Each magazine is worth its weight in gold to the true aquarist.

I had one of these, it was white. It grew to be very big and out grew it’s tank. I gave it to the New England Aquarium in Boston. How long do these fish live? I didn’t see where it said it?

A competing trait-based analysis can be found online here: http://reptileevolution.com/reptile-tree.htm

In that cladogram Osteoglossum and relatives split from other fish prior to the split between Actinopterygii and Sarcopterygii and prior to the split that gave rise to Palaeonisciformes.