In this earlier post, fellow AMAZONAS editor Matt Pedersen took a look at a great and frequently asked question in the hobby—how to get your hands on the true Altum Angel (Pterophyllum altum). This fish is generally considered to be in a special class among the freshwater fish—a ‘Holy Grail’ fish for some—difficult to obtain and even more challenging to keep. But, despite its reputation, the Altum’s allure is undeniable, and it continues to be highly sought-after in the hobby.

As luck would have it, I happened to be traveling in Colombia, which is where nearly all the true Altum angels in the trade are exported from. And, having just missed what was by all accounts a fairly good season for wild Altums, I was able to discuss the supply chain of this somewhat elusive fish with several of the exporters I visited in Bogota.

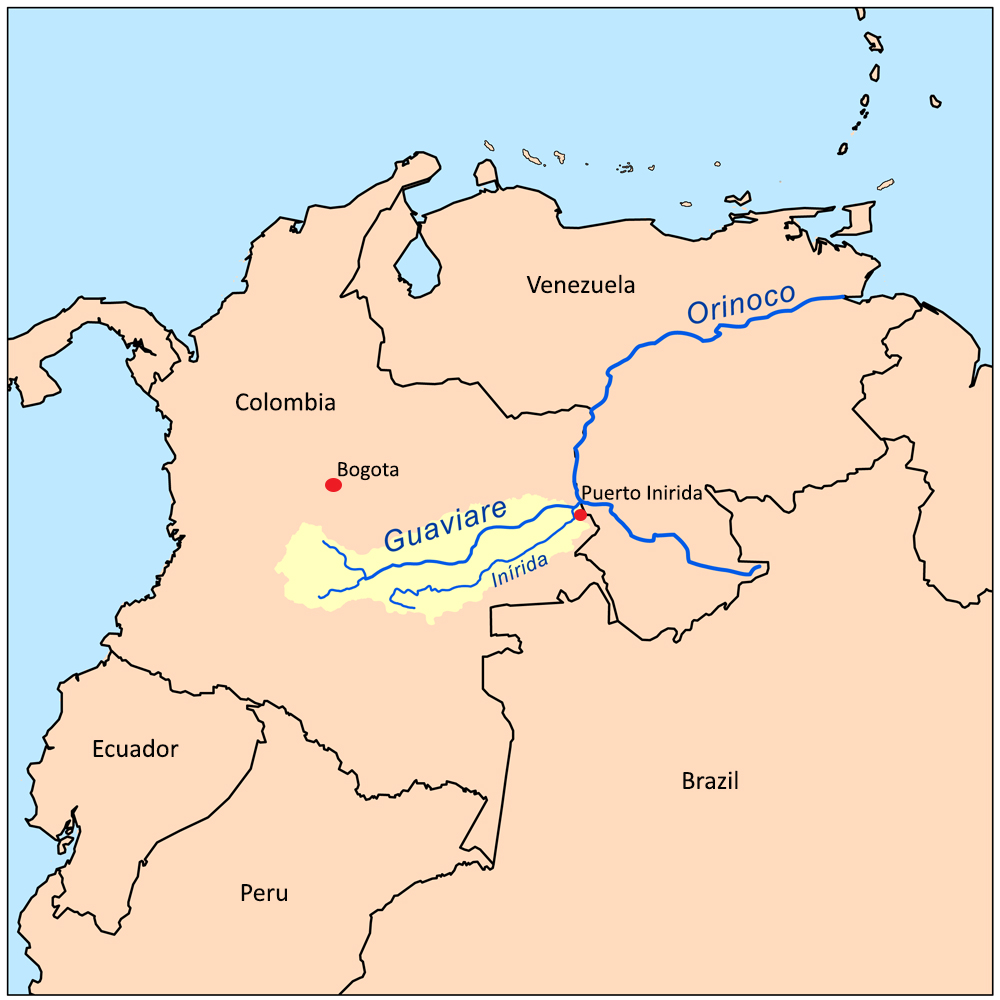

Map of the Rio Orinoco basin along the borders of Colombia and Venezuela, where most altums for the trade are collected. They make their way to holding facilities in Puerto Inirida before being shipped to Bogota for export

The true P. altum is found along the border of Colombia and Venezuela in the Orinoco river drainage, including the Rios Atabapo and Inirida. It inhabits blackwater lakes and slow-moving streams throughout the region. There are also populations of P. altum in the middle and upper Rio Negro in Brazil and Colombia, most likely a remnant from when the Negro and Orinoco rivers converged directly (until the rising Andes mountain range separated the river systems around 8-10 million years ago). A number of other populations have been given the moniker P. cf ‘altum,’ but none appear to decisively match the original description and holotype of the fish as described by Jacques Pellegrin in 1903.

Wild Altums in their natural habitat on Brazil’s Rio Negro. Fish from this population are rarely seen in the trade.

During the season for Altums—roughly July through October, when water levels are sufficiently low to allow for fishing—the fish are collected throughout their range. The official collecting season for these fish in Colombia begins July 1st, and in a good year it can run through December. Collection occurs in typical fashion for wild angels, with fishers going out by canoe in the dead of night and searching for the angels by flashlight. Once collected, they must make their way to a local distributor, who either purchases the fish directly from the fishers or by way of roving Patrones, who make the rounds to remote fishing areas. In the Orinoco Basin, there is only one major distribution point, the town of Puerto Inirida, which acts as a consolidation point for Northeastern Colombian and Venezuelan fish on their way to exporters’ facilities over 400 miles away in Bogota. But the Altum’s journey does not end there—due to their delicate nature, many of the better exporters will transfer freshly arrived angels to their larger holding facilities in Villavicencio, about 3 hours’ drive from Bogota.

Freshly collected Altums are often held in ponds like this one to recover from the stress of capture before being transferred to an aquarium

There, the fish are held in outdoor ponds and allowed to recuperate from the stresses of capture and transit while they are conditioned for export. The water in these ponds typically hovers between 78-80F, cooler than the Altum’s native waters and with a slightly higher pH, roughly 5.0-5.5. Once the fish are conditioned, they are transferred to aquariums in the Bogota exporter’s facilities in the city, where they will remain anywhere from 2 days to 2 weeks before being shipped to importers across the globe. Altums are notoriously difficult shippers, and are extremely sensitive to handling, poor water quality, and crowding. The long supply chain for this fish, and the fact that they may change hands 2 or 3 times before even being exported, is almost certainly a major factor responsible for wild Altum’s (very deserved) reputation for being difficult to keep in an aquarium.

Typical export facility in Bogota, from where Altum angels will be shipped out to wholesalers and distributors worldwide

Once imported, Altums face variable, and unfortunately sometimes less-than-ideal, care in the hands of trans-shippers, wholesalers and retailers. This is where a significant proportion of the health issues with wild Altums can take a turn from manageable to terminal. The better distributors and retailers, with appropriate handling practices, health management, and water quality, can really make a significant difference at this point in the supply chain and can determine whether a hobbyist receives relatively healthy or stressed, moribund fish. Sadly, as Matt’s experience buying Altums online illustrates, it is often the latter.

With a little insight now into the pre-export supply chain for these fish, I would hypothesize that a lot of hobbyists and retailers may actually be making things worse for freshly-imported angels, due to the long-held belief they need extremely low pH and soft water. The fish are going through a gradual increase in pH—from as low as 4.0 in the black water they inhabit to upwards of 6.0-7.2 at most exporters’ facilities—over the course of several weeks. Most importers in the U.S., even those that utilize special, lower-pH holding systems for Altums and other blackwater fish (like Segrest Farm’s huge softwater system I wrote about earlier this year), are still working with water between 6.5-7.5. Prevailing hobby wisdom says that Altums are blackwater fish, and the instinct for most hobbyists and retailers (myself included here) is to set up a tank for newly-imported wild Altums with low pH, high temperatures, and tons of tannins. I believe that this may be a mistake, as it exposes the fish to a large, sudden change in water chemistry from what they have been acclimated to and actually causes additional stress, rather than alleviating it. High temperatures (>82F) can also spur bacterial growth, potentially exacerbating minor bacterial fin and scale issues.

My suggestions for success with wild Altums are as follows:

- Start small—small Altums ship better and are generally easier to acclimate to aquarium life. Not too small, though, as very young fish are equally delicate as large adults and often arrive weak and emaciated.

- Keep your tank at a pH no lower than 6.0 for new arrivals, with 6.5 being what I would aim for. A mix of RO and municipal water will probably work best here.

- Don’t go crazy with tannins. One or two small Indian almond leaves might be useful here for their antifungal and antibacterial properties, but monitor the pH closely.

- My ideal temperature range for freshly-arrived fish would be 78-80degrees Fahrenheit, and no higher than 82 degrees. Watch for signs of disease, but don’t medicate unless you are reasonably confident in your diagnosis.

The Altum angel is undoubtedly one of the most impressive freshwater aquarium species available to hobbyists, and it continues to present challenges to even the most experienced hobbyists. Bear in mind the above suggestions are just that—suggestions based on my experiences with fresh imports in an aquarium setting and, now, having seen how Altums make their way from the Orinoco basin to export facilities and then on to home aquariums. Hopefully this provides a small bit of insight into what goes into the process of exporting, importing, and distributing this fish, and helps in some small way to improve the survival of newly-arrived wild specimens. I would urge anyone considering working with wild Altums to do ample research before attempting these delicate beauties. And if you’ve had success acclimating freshly-imported wild Altums, by all means share your methods in the comments!

Great article, read Matt’s as well, also great. So…. now would you two get together, compared notes and write an awesome husbandry article based on your successes!? Everything out there is copy and paste material taken from someone who had never even succeeded with altums!

Go to finarama.com. This site is devoted to the study of angelfish & you will learn a great deal. Trust me, you won’t regret it. I currently keep Pterophyllum leopoldi, granted, they’re not altums but it takes skill to maintain these combative critters!!! 🙂

There is a site devoted to wild angels, especially Altums. The people there are true pros. They taught me how to keep wild altums alive. They have a few members who have managed to spawn them. They do some things differently than the article wrote about and some the same. I have not been active on the site for a while because most of my 30 or so healthy altums were wiped out when health issues kept me from performing proper tank maintenance for many months. I have only 4 left which are about 2.5 years old. And they never reached their full potential as a result of the neglect. I should mention it took me a couple of tries before I had managed to keep altums alive.

If you are interested, the angel site I mentioned is one where you must be a member to read, but it is well worth it if one wants to try keeping altums. There are several good places one can buy them. For those interested in this a site, Google “finarama.”

And here is my gift to altum fanciers:

and

These are two vids about wild altums. They are in German with English subtitles and narration. The first documents collecting altums in the Rio Atabapo and the second shows them ending up at the Facility of Simon Forkel (a respected altum breeder) in Germany. Some of the fish you will see in the second vid are so beautiful it almost makes you cry. Please watch them on a big screen and in full screen format.

Chris, you are so right about Finarama.com. I enjoy that site immensely!!! My knowledge of keeping angelfish exploded. Guys, Mike Troxell is one of the few people that have managed to successfully breed Pterophyllum altum in captivity.

I had some altums back in the 80s when I was in the wholesale business. I don’t remember doing anything special to the water, I put them in with wild discus, but I think the thing that made it successful was that it was a big tank; over 200 gallons. In a tank like that the water is more stable, takes longer for change to happen. I had those angels for a long time. They started out with bodies about 2 inches in diameter. The fin height on them when they were full grown was probably close to 12″; they were huge fish.

Thanks for the youtube links. Really enjoyed those!

I have heard several times that Rio negro are rarer and look different than Colombian Altums. Has anyone seen both and give a comparison? Thx

Both are true – the Rio Negro “altum” is harder to come by in the trade and there are some slight morphological and color pattern differences. Check out the Nov/Dec 2016 issue of AMAZONAS, where we have photos and information about the distribution and status of Pterophyllum species through the Orinoco and Rio Negro basins. That should help clarify the differences (and similarities) between the two.

just write bulkshit for talking, there is not write fckn anything about acclimate to water, what kind of chemicals using for treatment dor columnaris, how to chsnge wster how msny percent etc. dont write anything then talk bullshit behind of exporter or collector even they are dont know but you also dont know anything just talk bullshit…. from turkey with love…

Thank you for this article. One of the best information source regarding Altums. I’ve tried keeping Altums for several years with much disappointments from earlier batches. Currently with 3 lovely ones in slightly soft water, ph7, temp 27C. Have acclimatised them to pellet food early. They’ve survived 2 bouts of columnaris attacks and Furan plus saved them. It hasn’t been easy caring for them but certainly worth the effort for such majestic amazon fish.