Article & images by Rachel O’Leary

Wherever plants or animals are domesticated and farmed, diseases and parasites are sure to be found. A number of parasites on freshwater aquarium shrimps are becoming more prevalent, apparently through the commercial aquaculture of several species—most notably those of the genus Neocaridina. The most common external parasites are found on the animals’ surfaces and appendages. These infestations probably rarely cause mortality in the wild, but under the stressful conditions often found in densely stocked aquaculture ponds and tanks they can get out of hand and negatively affect mobility, molting, growth, and function. Breeding and feeding may stop, and mortality may result. High infestation of the gills, as found with peritrich ciliates, can affect respiration and may be fatal. Parasites are easily transmitted between species, so it is important to promptly treat any affected specimens, quarantine new shrimps, and perhaps give all new animals a welcoming dip.

Scutariella japonica seems to be the most common shrimp parasite, and home aquarists in North America and Europe are reporting it with increasing frequency. It is a Temnocephalidan (an order of tubellarian flatworm) that typically lives in the gills or mantle of the shrimp, evidenced by a series of fingerlike appendages extending from the rostrum. It is well known to occur naturally on populations of Neocaridina distributed in East Asia, covering China, Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. Since the 1970s, live Neocaridina have been imported routinely into Japan for the recreational fishing of marine and brackish fishes, and are also sold there in the aquarium trade. China became the main source for imported shrimps in the 1990s. The spread of Scutariella through the use of the shrimps as live bait was documented in a study by Niwa and Ohtaka (2006). Out of 629 shrimps examined at the Kansai Airport, 365 were infected; they were then distributed to neighboring areas. I myself have regularly seen infestations on Neocaridina shrimp, specifically those imported from Taiwan.

Vorticella_patellina-shown in a vintage illustration, circa 1838. Greatly magnified.,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,

In a study published in the Journal of Natural History, Neocaridina shrimp were collected from 18 sites in five provinces in Southeastern China from 2007 to 2009; out of a total of 1,681 shrimp collected from 18 sites, most hosted at least one ectosymbiotic worm, and S. japonica occurred in 25.2 to 100 percent of them. The affected shrimp had infestation of the branchial chambers, identifiable cocoons in the gills, and visible worms on the surface of the rostrum.

Salt Cure

Scutariella japonica is a shrimp-specific parasite that feeds on detritus in the water and the plasma of the shrimp. It attaches with a suction cup base and lays its eggs in the gill chamber, most often in rows; the eggs can be identified by visual inspection. When the shrimp molts, the eggs within the cocoons hatch and re-infect the colony. It is especially important to remove molts during and following treatment. Infestation can be seen upon close visual inspection as a series of stalky appendages extending from the rostrum above and between the eyes. Under magnification (a hand lens is very helpful), slow undulation of the parasites can be seen.

Because Scutalleria is spreading widely in the aquarium trade and in hobbyists’ tanks, visual inspection and treatment are extremely important so as to prevent transmission to healthy established colonies.

Luckily, Scutalleria is very easy to treat in several different ways. I find it most effective to dip visibly infected newcomers in a concentrated solution of 1 tablespoon of salt per cup of tank water. The shrimp are placed in a well-oxygenated container for approximately 30 seconds, then removed. All visible parasites should be gone after this, and I have seen no shrimp mortality using this treatment. It is important to watch the shrimp closely during treatment and remove them as soon as they show any signs of stress (inactivity, rolling over, etc.), then put them into fresh water immediately after treatment. The Asian Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances recommends culturing shrimp in slight saline conditions (5–10 ppt) to prevent infestation and mortality.

An alternative treatment is to use Praziquantel at a concentration of 2.5mg/L in the tank. A single treatment is generally effective, though a second one may be needed after a few weeks, especially if molts are not consistently removed from the aquarium. Some breeders have reported good results using Seachem’s ParaGuard.

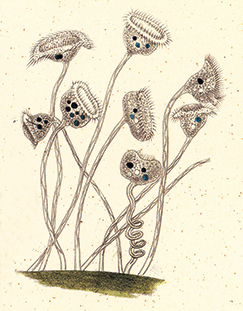

Several other parasites are also becoming more prevalent in freshwater shrimps, including Vorticella, a ciliate protozoan evidenced by a conspicuous ring of hair-like stalks found in clusters but attaching independently to the rostrum and appendages. It can be treated in the same manner as Scutalleria japonica.

The parasitic protist tentatively identified as Ellobiopsis sp. appears as green, elliptical to elongate cylindrical stalks penetrating into the body of the shrimp. This pest can affect motility and breeding, which often leads to secondary bacterial infections evidenced by opacity and whitening of the body of the shrimp and usually leading to mortality. The best treatment protocol for this pest is not known; saline treatments are ineffective, but it appears that this protist might be photosensitive, and a darkened aquarium in combination with anthelmintics could be effective.

Given the growing problem of shrimp pests, sellers and distributors should always use proper quarantine and treatment procedures before passing shrimps on to stores and home aquariums.

COMMENTS INVITED! Do you have experiences with these or any other parasites of freshwater shrimps? Please add to our file of information.

References:

Niwa, N. and A. Ohtaka. 2006. Accidental introduction of Symbionts with imported Freshwater shrimp. In: Koike, F., et al. (eds), Assessment and Control of Biological Invasion Risks, World Conservation Union, Gland, Switzerland, pp. 182–86.

Nur, F.A.H. and A. Christianus. 2013. Breeding and Life Cycle of Neocaridina denticulate sinensis (Kemp, 1918). Asian J Animal Vet Adv 8: 108–15.

Ohtaka, S.R., et al. 2012. Distributions of two ectosymbionts, branchiobdellidans (Annelida: Clitellata) and scutariellids (Platyhelminthes: “Turbellaria”: Temnocephalida), on atyid shrimp (Arthropoda: Crustacea) in southeast China. J Nat Hist 46 (25–26): 1547–56.

“..concentrated solution of 1 tablespoon of salt per cup of tank water..”

I have a 3 and 10 gallon tanks. Whats the dose? How many tablespoons forneach tank?

For a tank treatment your best bet would be to use a hydrometer. So you can test for salinity or specific gravity.

I think the intent was to prepare a small volume treatment – ie. one or two cups in volume. Place the shrimp to be treated into that small volume of saline, remove as soon as signs of distress are seen, then transfer to your UNSALTED tank.

Jim R.

“..concentrated solution of 1 tablespoon of salt per cup of tank water..”

I have a 3 and 10 gallon tanks. Whats the dose? How many tablespoons for each tank?

Thanks for the great article. I’m now currently salt bathing my 40+ shrimps after chasing them around in my 20gal planted tank for 3 hours to get them out. I gave them so many great hiding spots, it was tough as **** to find them all!

Ellobiopsis sp. Any updates? I have this very prevalent through one of my shrimp tanks I would love to find a solution.

The salt worked great. I had a few that I bought in a local fishstore that had Scutariella japonica. At first I did not recognized it, until the white wiggly thingies started to develop between the eyes. Thank you so much for this article. Not only informative, but also a great solution for treatment.

Is kitchen salt ok to use?

I’m not going to get into the debate over whether table salt is good or bad to use, but for simplicity’s sake I’ll simply reiterate the long-standing dogma that arguably one should not use “iodized” table salts, but kosher salt is OK for aquarium use. Of course, there are many aquarium-specific salts on the market ranging from simple “aquarium salt” to the wide array of marine aquarium saltwater mixes. Since I keep marine aquaria as well as freshwater tanks, I use my marine salt whenever I need salt for a freshwater or brackish tank; it’s here, it’s convenient, it’s safe, and in the grand scheme of things I use relatively little so the “expense” isn’t really felt.

My ghost shrimp have a red wiggly thing between their eyes n today I noticed some are dark..some of my shrimp are yellow or white..do you guys think it”s the same thing?

One of my shrimps was infested with ellobiopsidae. She remained active though it was apparent her movements from her little swimerettes were impeded by the mass of fungus/protist. I did a salt bath at 1 cup of tank water with 1 teaspoon aquarium salt every other day (for about 1 min at a time), and about every three treatments I’d give her an extra day off. It appeared that she was grabbing at the fungus while in the bath, like it was itching or bothering her. After about two weeks, it has completely gone away. She has now been free of the pest for a week and a half. I’m wanting to return her to her colony but I am hesitant for now.