Although most of my time in India was spent in and around the bustling metropolis of Kolkata, I was able to spend a few days in one of the most unique aquatic ecosystems I have ever encountered—the vast estuary created by the Ganges delta known as the Sundarbans. Only a few hours drive from Kolkata, the Sundarbans (also sometimes spelled Sunderbans) straddles both sides of the border between India and Bangladesh along the Bay of Bengal and encompasses over 10,000 km2. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and renowned for its native population of Bengal Tigers. It is also considered to be the largest contiguous area of mangrove forest in the world, with 78 distinct species of mangrove having been identified. From an aquarist’s perspective, the Sundarbans is home to an enormous diversity of aquatic life but in a setting and habitat type we often overlook.

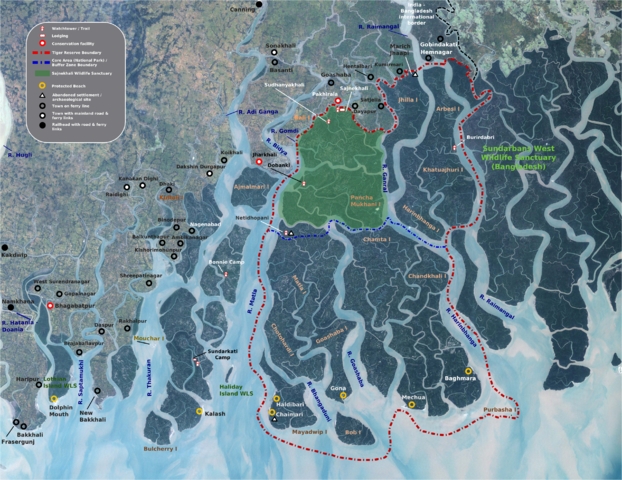

Map of the Sundarbans, with National Park and Tiger Reserve boundaries demarcated (Wikimedia Commons)

Situated as it is at the juncture of the Bay of Bengal (on the Indian Ocean) and the outflows of the Ganges and Brahmputra river systems, the Sundarbans may be one of the most dynamic ecosystems on the planet—it is hourly, daily, and seasonally in a state of perpetual change. We have a tendency to think of the natural habitats of fish (especially those that we keep) as fairly static environments, rather like the aquariums we keep them in. We have a general sense of acceptable parameters and we do our best to keep things within this small range. Here in the Sundarbans, however, such parameters as pH and salinity will fluctuate significantly every single day—and yet the unique estuarine life of the region is remarkably adapted to these constantly changing conditions.

Perhaps the most important influence on water conditions in the region is the daily tides—as gravity pulls seawater inward towards the rush of freshwater on a 12-hour cycle, there is a resulting increase in salinity and pH roughly twice daily. The mangrove islands and root systems help to moderate the influx of seawater, but even far upstream you will encounter noticeable daily salinity gradients which correspond to the tides. Along with the daily tidal influence, there is also a large seasonal variation in the amount of water the tides carry inland as well—during extreme high tides the overall water level can rise as much as 2 meters, flooding large portions of the forest and opening up extensive habitat and foraging grounds for aquatic life.

The other major factor which plays a role on both the level and salinity of water in the Sundarbans is the monsoonal weather cycle which impacts most of South and Southeast Asia. This is results in distinct dry and rainy seasons during the course of the year, which in turn influences the water level and outputs of most major river systems. During the dry season, the Ganges’ water level drops substantially and the amount of fresh water it deposits into the Sundarbans is greatly reduced (resulting in overall higher salinity and pH). As the monsoon rains inundate the Indian subcontinent, the rivers swell and much of that rainwater makes its way into the delta, raising water levels and pushing back the saline water to create more of a light brackish environment.

As you can imagine, these immense daily and seasonal shifts in water parameters greatly influence the abundance and distribution of aquatic life in the region. During the dry season many marine species (especially juvenile fish) can be found far upstream, taking advantage of the shelter of the mangroves and the relative abundance of food. Conversely, during the rainy season it is not uncommon to find traditionally freshwater species close to the mouths of the river only a few kilometers from the ocean. And of course throughout the year, those species adapted to live in a brackish or euryhaline environment can be found at either extreme, their feeding and reproductive strategies synchronized with the seasonal and tidal variations.

Mangrove trees form the dominant structure of the ecosystem here – both above and below the water’s surface

Just like reef building stony corals the world over, the dozens of mangrove species found in the Sundarbans are the building block of the entire ecosystem, providing critical structure and physically shaping the habitat in every way. Unlike most coral reefs, however, the mangroves’ influence extends both above and below the waterline. Their enormous root systems, when submerged, provide an almost unimaginably broad array of habitat—from hosting sedentary invertebrates like sponges, barnacles, and cnidarians to acting as critical nursery habitat for juvenile fishes and marine mammals. Above the water’s surface, the mangroves’ aerial prop roots and the branches and leaves of the trees themselves are home to an equally important contingent of species. From reptiles like the ubiquitous water monitor (Varanus salvadorii) to avian fauna like the kingfishers, ibis, and storks I saw in abundance, the mangroves are the undisputed cornerstone of this entire ecosystem. Several species of monkeys can often be seen on mudflats catching crabs and fish among the mangrove roots. Even the famed Royal Bengal Tiger (Panthera tigris) of the Sundarbans lives its entire life among the mangroves, stalking prey from behind the dense tangle of roots and branches.

Not only do they influence the ecosystem by providing habitat, but mangroves in the Sundarbans actually play a role in the water flows and geography of the region. Mangrove roots trap sediment and silt, which can over time create a landmass out of what was once just shallow water. The species and distribution of the trees is constantly changing the physical layout of the area—with new islands emerging while others recede back into the waters. The immense root systems also act as something of a barrier against the effects of the incoming tide—pushing back against the rush of saline water from the Bay of Bengal and moderating its potentially destructive effects on the estuarine life closer to shore.

The seemingly plain and monotonous mud flats and mangrove islands of India’s Sundarbans are, in fact, anything but. This vast estuary is a teeming, dynamic, and fascinating ecosystem like none other on earth—and for the aquarist looking for something a bit ‘off the beaten path’, it represents a chance to create a truly unique aquatic environment. Whether a terrestrial setup focusing on the entertaining antics of mudskippers and fiddler crabs or a slice of the waters’ edge with estuarine fish darting about the mangrove roots, a Sundarbans biotope aquarium would certainly be a worthy challenge for any creative aquarist or aquascaper. I hope the information outlined here may serve as inspiration for fellow hobbyists to attempt to recreate a little slice of this amazing ecosystem. In the next installment I’ll take a closer look at some of the aquarium-appropriate fish species found in the Sundarbans and how best to replicate their habitat in the aquarium.

It is great to hear that some one is documenting the diverse part like the sundarban. It is a great place for aquarist. I have visited the place for sometimes. Yet i would like to visit them again and again, everytime a surprise is waiting for me. Great going.

Very informative…….looking forward for many more documentations of the sundarban

HI, Mike Thanks for sharing this incredible article with us. I am very much interested in visiting Sundarbans. Can you please suggest me any touring guide service provider name, who can help me to visit Sundarbans?