A group of the highly endangered Devils Hole Pupfish, presumably in their native habitat. Image by Olin Feuerbachr / USFWS | CC BY 2.0

News broke today in A story released by the LA Times last April announced that researchers at the Ash Meadows Fish Conservation Facility have spawned the critically endangered Devils Hole Pupfish, Cyprinodon diabolis, for the first* time in captivity, a “biological breakthrough that could save the nearly extinct species.”

This species has lived a highly-isolated existence, restricted to a single geothermal aquifer-fed pool within Death Valley (Devils Hole, located within the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Nye County, Nevada, a detached unit of Death Valley National Park).

Devils Hole, the sole location of the Devils Hole Pupfish. USFWS | CC BY 2.0

There is vast speculation on how the Devils Hole Pupfish found its way into this tiny water body and how long ago it happened; one of the most interesting ideas I recently came across is the speculation that the fish themselves may have been introduced by humans, perhaps only hundreds or thousands of years ago. Regardless of how it got there, and how long it has been there, the Devils Hole Pupfish is small (max 1″) and lives only 1 year, with an annual population ebb and flow each year, in a very small habitat, hanging in the edge while continuing to puzzle scientists and conservationists.

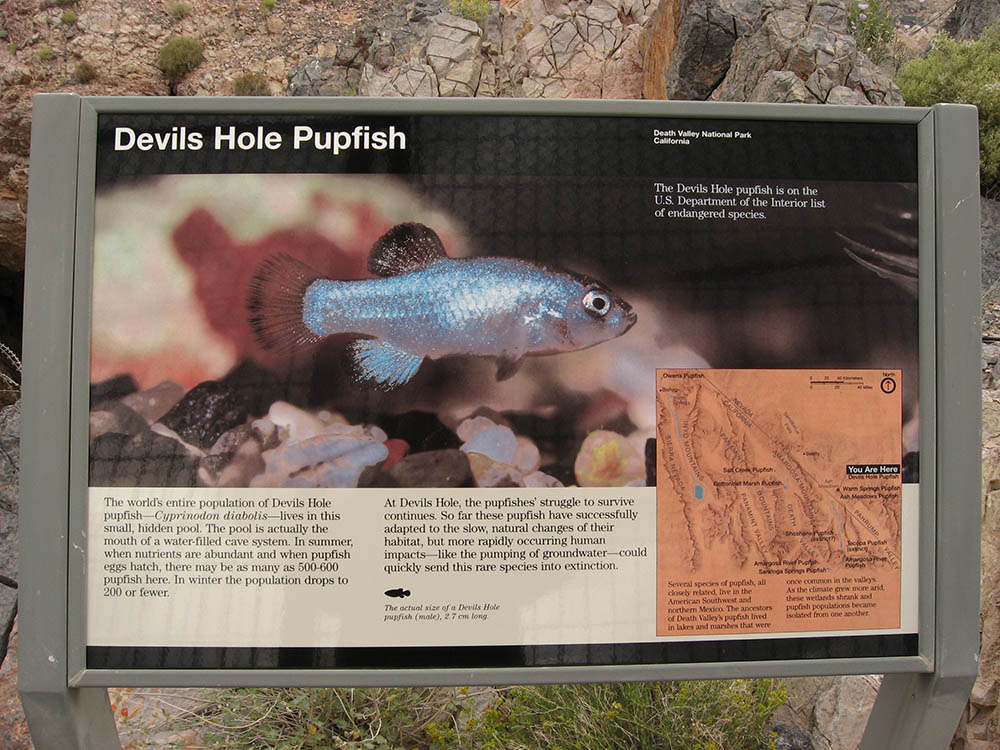

Informational signage at Devils Hole telling the story of the Devils Hole Pupfish – image by Ken Lund |CC BY-SA 2.0

Never plentiful (or perhaps better said naturally-rare), the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) reports that “Devils Hole pupfish numbers have not exceed 553 individuals.” Population size remained relatively stable from the 1970s into the 1990s, with an average of roughly 324 fish. Starting in 1997, the population declined, and continues a downward trend largely unabated. With population numbers hitting all-time lows in 2013 of just 35 fish in the wild, despite receiving Endangered Species Act protections in 1986, the situation is grim for this somewhat iconic fish. Reports in late 2014 suggested that there is a roughly 30% (28-32%) chance of extinction for the species in the next 20 years.

Recent studies had concluded that the removal of eggs for captive-breeding efforts was less likely to have an impact on the species; in 2013 eggs were collected and hatched, resulting in 29 captive Devils Hole Pupfish (13 female, 16 male) growing up at the Ash Meadows Fish Conservation Facility in Nevada.

Devils Hole pupfish propagation tank – USFWS | CC-BY-2.0

As reported, these captive-raised specimens have produced the first captive-spawned eggs, starting the next generation of “arked” fishes (also known as a “refuge population”). The LA Times story suggests that in a couple generations, this could lead to 1,000 or more captive specimens; I’d like to note that would be nearly double the highest recorded naturally-occurring population size since records were kept.

As I read this story, I wonder what is next for the project. Having researched the act of conservation breeding for the book Banggai Cardinalfish, some interesting numbers are worth consideration. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has published extensive documentation on the conservation breeding of fish species. In short, a minimum randomly-breeding population of 50 specimens is required for short-term genetic fitness, but 500 is the minimum recommended for long term preservation (with, incidentally, a number more like 5000 being a “platinum standard” to account for genetic drift and retention of all genetic diversity). The most interesting proposition to note is this; potentially, a population of fishes could be squeezed through a bottleneck as small as 5 individuals, and so long as the population is rapidly brought back to 500, the species should be able to recover. Knowing these figures, it gives me hope that the aquaculturists at the Ash Meadow’s Facility are well on their way to building a backup population should things continue to get worse in the pupfish’s natural habitat.

Perhaps most noteworthy to our readers was the debate among our AMAZONAS Magazine Facebook audience over efforts to save this species. Last November, we shared the op-ed “Should We Really Save The Devils Hole Pupfish?” by onearth’s Jason Bittel. The story’s social media subtitle, “Meet the world’s rarest fish. We’re spending $4.5 million to save it.”, sparked an interesting mix of sentiments I’ll summarize and paraphrase as “Of course we should do this,” to “have we lost all perspective..it’s just a fish…people can’t even buy groceries!”

Public sentiment aside, it looks like we spent those millions; the LA Times reports that most likely, the offspring of future successful breeding will be transferred to “a new $4.5-million, 100,000-gallon tank at the federal Ash Meadows Wildlife Refuge — a replica of Devil’s [sic] Hole less than a mile away.”

The Devils Hole pupfish propagation facility, published April 2014 – USFWS | CC-BY-2.0

With forecasts for continued wild population declines, and declines occurring with the failure of on-site attempts to reverse the population’s downward trend, plus globally warming temperatures and groundwater depletion being fingered as the likely causes for this species’ decline, is all hope lost for the Devils Hole Pupfish in the wild? Will we one day have the Devils Hole Pupfish solely as a captive species, or can the environmental problems being blamed ever be reversed?

At a cost of $4.5 million plus, are we saving a species that simply no longer has a home? If so, what then should become of the Desert Hole Pupfish? Freshwater hobbyists already work to keep some of our favorite little gray fishes that the world doesn’t really “care about” around, and we do so voluntarily. Does the Desert Hole Pupfish need to find a new home, a new use, and a new purpose in life? If so, might that one day be within the aquarium hobby? With the first good news for the Devils Hole Pupfish, one can’t help but speculate.

A lone Devils Hole Pupfish – by Olin Feuerbachr / USFWS | CC BY 2.0

For now, I’ll simply extend my congratulations to the countless individuals who worked so hard to reach a captive-breeding milestone; a new chapter of hope can now be written.

*Editor’s update – Bruce Stallsmith kindly brought to our attention that this may not in fact be the first time Devils Hole Pupfish were spawned and reared in captivity, citing the three fish reared from egg to adulthood as reported in:

Egg viability and ecology of Devils Hole pupfish: Insights from captive propagation

James E. Deacon, Frances R. Taylor and John W. Pedretti

The Southwestern Naturalist

Vol. 40, No. 2 (Jun., 1995), pp. 216-223

This type of project should be so commonplace. If the research, construction, and maintenance should be replicated for a wide variety of species worldwide. The cost would be less, the outcomes would be more predictable and the justification would be obvious.

Carry on, and you inspire more and more people.

In 1972 I published a piece in Smithsonianmagazine, entitled, “Big Troubles for a Tiny Fish”, which concerned the devils hole pupfish and the difficulties it was facing. Thru court cases, even the Supreme Court, the tiny critters hung on. Heavy pumping of water from the Ash Meadows aquifer was then a major concern. I’m happy to hear that captive pairs are mating and youngsters being raised successfully. Those tough little guys are still proving their resiliance. Hurrah for them and those dedicated folks who are in the struggle to aid in their survival.

We visited Devils Hole twelve years ago and saw the fish from afar. Some thoughts regarding the preservation of rare species of anything: nothing in nature is static, and the moment a species loses adaptibility it is defacto extinct. But if a species hybridizes, or breeds back to the greater parent gene pool, the genes are not lost but preserved in the descendants, and will give a more variable, genetically diverse and adaptible creature. If I were “God of the Devils Hole pupfish”, I would hybridize the remaining fish with their close relatives, spread them to suitable habitats, and let hobbyists breed them. I have learned from my own hobbiyist efforts the more I gave away plants and animals, the more likely I could recover them if something happened to my population. Domestication can preserve animals and plants by repurposng them, such as has happened with horses and cattle. And by spreading them around in the wild, we would be helping them to continue their life job of contributing to the beauty and utility of the earth, and continue their evolution, instead of being static.

In my experience with pupfish in aquaria I have witnessed the durability of the Florida flagfish / pupfish from egg to adult , tough little fish them flagfish , they eat a wide variety of greens greens wise , they love broccoli , and carrot greens and them Florida flagfish clear the pesky invasive hair algae that I now gather is planet wide , the flagfish devour most of the prolific easy level aquarium trade plants , i grow those in a separate tank for replenishing the greens table. And yes they’ll eat their eggs and young . I collect their eggs with yarn spawning mops , they spawn around the dates of the spring and summer full moons from May through September in my tank , I get hundreds of eggs every summer , I just put the spawning mops / eggs in a water heater catch basin on my patio that is murky with leaves and muck from a local pond , additionally I throw carrots into the patio pond for copepod generation and wait till early September to net out my next generation of fish which can be in the hundreds , pupfish in my estimation are really cool and could be of economic importance in many ways , just use your imagination , the hot water adapted varieties could someday be introduced in the seemingly inevitable climate change hot water ponds of the future , yeah the pupfish are small but heck people eat sardines and sardines are small , protein , that is just an example of imagination usage so all you climate change politico hot heads calm down , yup I believe any little fish is of value , without little fish there would be no big fish …