Whether you like it or not, lots of animals have proclivities – urges – of a sexual nature that go beyond respecting any species boundaries. I’m sure we’ve all kept guppies at some stage, and know the degree to which they’ll harass anything and everything. I’m pretty sure I’ve seen one getting it on with a snail, once.

I’m no prude, though I’ll concede that I’ve never found any domestic livestock arousing. I also fully appreciate that sometimes in the animal world chalk can find itself in bed with cheese, and ‘oddlings’ can result. It took no great spark of genius to realise that with a little intervention, various creatures could be put together, have a little Barry White played to them over candlelit dinners, and the resulting chimeras had a saleable charm about them. Siegfried and Roy, after all, did very well out of someone realising that different tigers could be blended together in a big genetic blender. Imagine how much their supplier must be charging for those ‘desirable’ white felines.

But from a fishkeeper’s perspective, what I think we need to be aware of is the degree to which our interference and encouragement of this process can impact on the hobby as well as the world at large.

I’ll go gently, as I know that some countries have a much more relaxed attitude to hybridisation than others. In my native UK, we have a near incoherent fear of certain Frankencreatures entering the food (and pet) chain. Our terror at genetic modification here would lead outsiders to believe that upon masticating our first mouthful of genetically modified corn, we’d all sprout tentacles and crawl back in to the sea. Admittedly, our fear is based in no small part on certain facts, widely publicised by mainstream media. Escapee genetically modified (GM) trout have been found to breed with indigenous populations, creating morphs that outcompete the natives with devastating efficiency.

In fact, for a nation that went up against the Nazis, we often seem frivolously close to taking a eugenics slant to ensure the purity of bloodlines. This mindset hasn’t always led to rosy outcomes, and over the last decade or two, certain canine associations drawn our attentions to the plight of certain excessively line-bred animals, like the classic British bulldog – a squash-snouted, wheezing wreck of an animal, far removed from the breed standard of 50 years hence. Yet still, on some dogged and ignorant cultural level, we love a thoroughbred and loathe a mongrel.

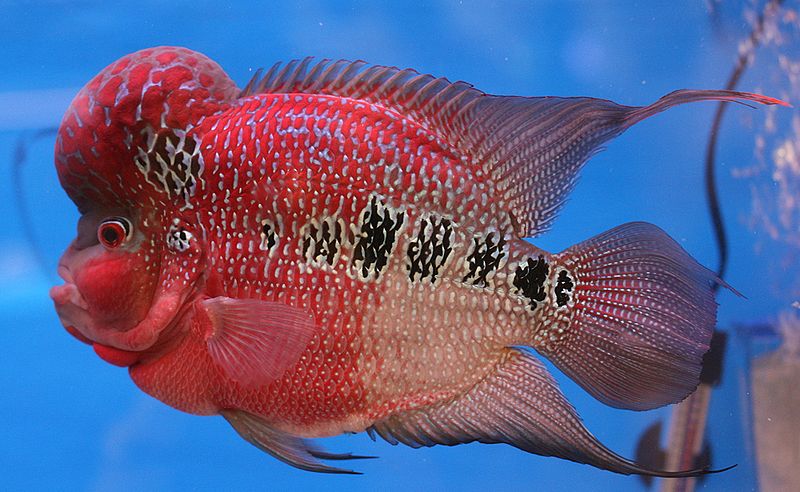

Enter the hybrid fish. In some circles, the following of the likes of Flowerhorn cichlids is vast, and why not? The Flowerhorn is a product, designed for a purpose, and it fits that purpose well. It’s colourful, it has a showy head, and it’s meant for aquaria. What’s the beef? This is ‘pimp my fish’ drawn out to its logical conclusion.

Well, critics are quick to note that when these fish escaped into the wild in Malaysia, they tore into the local species, messed up the ecosystems of ponds and rivers, and started breeding the way cichlids do. Kind of like the way Pterois lions are rampaging around American coastlines, snorting up native species with utter impunity.

But I’ll get hands up straight away – this is a different problem, requiring a different solution. Hybrid or not, escapees are down to irresponsible aquarists, and frankly the same would be expected from any Amphilophus species that suddenly found itself in a new habitat full of food, and with a willing sexual partner in tow.

This isn’t to say that hybridisation doesn’t have some kind of influence on the rate at which an escaped fish can become a problem. Enhanced colours of an imposter can be more appealing to fish than the blander, local bucks, and females can flock accordingly. The idea that hybrid fish are immediately at a disadvantage should they escape may be dangerously erroneous, yet remains strikingly popular. Sometimes the ladies like the quirks; that’s why peacocks have those absurd rumps.

This is speculation for the best part, on my behalf. Whether a wild hybrid population would destroy an ecosystem faster than its purer genetic ‘superiors’ is hard to say, and hazardous to replicate in any experimental setting. But it is a potential risk to be aware of.

However, what worries me (and others) is our complicity in accepting new variants of fish – of which Flowerhorns are a prime example – without question or criticism. It worries me because the very concept of Flowerhorns, of creating a ‘designer fish’, sits on the rim of an enormous ethical cavern.

Why is this? Because the variations occurring to the fish may be extreme, compared to the originals that conceived them. Massive humps, bulbous eyes, and extended tails are inconvenient anomalies for the creature that has to live with them. I recall finding the skull of a Parrot cichlid, cleaned and reassembled, with jaws askew and facial bones pointing every which way but. It doesn’t take a genius to establish that most of what is happening to these fish is inhibitory, and not advantageous to them. From here it’s a short step to state that what we’re doing is ‘implanting disability’ in to the fish, which is itself only a tiny semantic hop from saying that we’re potentially reducing happiness and increasing their suffering, or capacity to suffer.

And once we’re into the realms of increasing the level of potential suffering to the fish involved, it’s a damned brave ethicist who’ll try to argue that this can be a good thing.

Flowerhorns have pretty prominent humps, if you hadn’t noticed. Image credit: Lerdsuwa, Creative Commons.

It’s a slippery slope, for sure. If we accept hybrids, then we become indifferent to the continuation of the hybrid train of thought. If a fish with a big hump sells, then maybe one with a bigger hump will sell better. Before we know it, we’ll be saturated with monstrosities, because we left it too late to dig our heels in.

But there’s more to it than this. Falling back on the sanctity of my UK-derived semi-eugenics, I fear for contamination of bloodlines. The catch is, once hybridisation occurs, then there’s no going back. If I mix (say) a Great White with a Conger Eel (for argument’s sake), then no matter how much breeding I do after, my shark’s always going to have something ‘eely’ about him. This is real basic stuff, but it matters.

It matters because wild fish populations are being extinguished at alarming rates. Recently, Matt Pedersen wrote about Redtailed Sharks being found in the wild – a single specimen – which was exciting news. The trade’s full of the things, and hopefully one day, someone might find a way to reintroduce some by using specimens from the industry. Currently, that’s a conservation no-no, but the kinks are being gradually ironed out. But what a tragedy it would be for this one individual to disappear, and for all of our hobby based examples to have been tainted at some point in the past, mixed with foreign cyprinid blood that means they’re forever destined to stay away from wild environments.

Let’s assume for a moment that some Amphilophus species are wiped out in the wild – say from a pesticide leak, or something. A team of scientists decide that the region is ripe for reintroduction, and some fish are found that might be able to go back from an aquarium. But at the first DNA swab, the whole thing comes crashing down because the population were contaminated by hybrids some ten generations back. I exaggerate the point deliberately, but I’m sure you can see the angle that I’m taking.

Lastly, I’m not sure it’s entirely fair on the fishkeeper. A lot of aquarists out there – a surprising number, if I extrapolate from the ones I know personally – are keen breeders. They are owners of species tanks and biotopes, and are trying their darndest to keep things as authentic as possible. Many are flirting with the concept of ‘Citizen Science’ whereby observations on aquarium fish are being used to build strings of data that might apply to wild population management. To assume a hypothetical case, someone might make fascinating inroads to the behaviour of some commonly kept cat or cichlid, only to find later on that the experiment has been undermined by the inclusion of foreign blood and behaviours.

But it’s also economically stifling for the keeper of ‘clean’ lines of fish. If I wanted to breed a line of Synodontis in the UK, I’d have to completely avoid the confusing, jumbled variants on sale here. Unless I were importing wild, I could near guarantee the presence of imposter DNA in any species purchased; it’s that rife. Subsequently, as a hobbyist spawning and selling on S. petricola or similar, I’d expect knockback after knockback when trying to pitch them out. Without the pedigree, such fish are chaff tankfillers, but their long term worth is nothing. And as I said earlier, once that path is trodden, there’s no going back. That bloodline is forever tainted, like something from a Harry Potter storyline. Worthless. No wonder, then, that breeding enthusiasts have increasingly opted for ever more obscure species, far from the beaten track, where farmers won’t find them and force them to cross with a Platy.

Lastly, and offering myself up for the battering to follow – it’s just in rather poor taste, is it not? Why would anyone want to take elements of Convicts and elements of Midas Cichlids, fused together to make something not as good as either? There’s plenty of gorgeous fish out there in native form already. Stop thinking you can do better than countless years of evolution and take a moment to think about the fish in all of this. Perhaps, just perhaps, it doesn’t want eyes on stalks…

I agree there are enough species of fish in nature that is not necessary to create hybrids, but you mix up some facts. Natural hybridisation is quite common without help from humans, they don’t wipe out habitats and instead they drive the evulotion forward. In few cases humans may have some negative impact increasing natural hybridisation through mechanic destroying of habitats, over fishing etc. not really meant to be. Fish is a renewable resource, they reproduce each year and if the wild fish managing was better we could use this resource “for ever”, unfortunatly we abuse this resource, necessary with restrictions how we use it, even if that not work in practical it drives the ornamental fishery to create manmade hybrids since they not can use the natural resource of fish. We are emptying the oceans, the rivers for what… Food? Yes, but not only a direct food for humans, it’s a resource to produce everything from soy to pigs, we use fish as fertilizer, we feed the animals with animals to produce different kind of meat, fish meat become other fish meat, pig meat or chicken meat… what we will do that day we not have any fish?

The final conclusion I forgot above, there are no wild fish management of our resources when it comes to fish, not sure if there are any management for other animals either.

A very good opinion piece.

Hybridizations should be discouraged for the very reasons mentioned above and more.

We can not trust the public either to do the right thing, hence there is a need for regulation in the hobby, including internal regulation. Peer pressure is an effective control.

This is an excellent article.

what is omitted is the commercial greed of producing fish that are more monstrosity than fish. In the end, morality and ethics are very secondary to “how do I make more money”.

Harvey Hammer

USA

I agree with the article and the comments of Jim and Harvey. I would respectfully point out something in response to Janne’s comment about natural hybridisation. If such occurs naturally in the wild, it will be part of the overall “plan” of the natural world through evolution. This is how all of us including our beautiful aquarium fish got to where we are today. But natural evolution is a very, very different thing from humans creating hybrids in any artificial manner. The latter is, as the article and others point out, fraught with dangers but sadly these matter not to those making money out of them.