New Paper Suggests Sustainability is Not Just a Discussion for Saltwater Aquarists

By Ret Talbot

Over the past few years, freshwater aquarists may have noticed activists increasingly targeting their saltwater counterparts, seeking, for example, the complete ban on marine aquarium fish collection and exports from Hawaii. Other advocacy groups are attempting to have some common fish and coral species protected under the Endangered Species Act.

While many attacks on the marine aquarium trade are bluster born of emotion and largely devoid of accurate scientific data, there do exist real concerns about the overall sustainability of the global marine aquarium trade. Those concerns are, in the best of cases, spurring discussions amongst stakeholders—amateur aquarists, importers, representatives of public aquaria—about the future of the trade and its impacts on ecosystems, fishers and fisher communities in impoverished developing island nations.

The same level of debate is not occurring amongst freshwater aquarists. This is generally assumed to be because the freshwater trade is primarily reliant on aquacultured livestock, not animals collected from the wild.

While roughly 90 percent of the marine aquarium trade’s animals originate on reefs, only about 10 percent of freshwater aquarium fishes have ever seen a natural ecosystem. Is the freshwater trade therefore above reproach when it comes to sustainability? Perhaps not: A paper just published in the journal Biological Conservation about India’s freshwater aquarium trade is the most recent paper to document problems that may warrant freshwater aquarists taking a more active role in the aquarium sustainability dialog.

Threatened and Endangered Endemic Fishes

At the heart of the Biological Conservation paper is the concern that India’s freshwater aquarium trade is having a detrimental impact on endangered, highly endemic fishes frequently harvested and exported for aquarium usage.

Just shy of one-third of all freshwater fishes exported from India for the aquarium trade between 2005-2012—the paper pegs the number at about 1.5 million animals—are listed on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species as either threatened or endangered. While some of these 30 species are exported in small numbers, others such as the Malabar Pufferfish (Carinotetraodon travancoricus), Zebra Loaches (Botia striata), Denison Barbs (Puntius denisonii) and P. chalakkudiensis (the latter two commonly called Redlined Torpedo Barbs or RLTBs) are exported in relatively large numbers. Most of the fishes are exported to Southeast Asian markets, where some are re-exported—many no longer bearing their country of origin information—to North America and Europe.

In addition to the aquarium trade’s impact on threatened and endangered species, the paper explores the impact on India’s endemic species. According to lead author, Rajeev Raghavan of University of Kent’s Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE) in the United Kingdom, at least 22 endemic species of freshwater fishes are threatened by India’s aquarium trade. While nine of them show a continuing decline in their populations, they continue to be harvested with very little (if any) science-based, adaptive fishery management in place. What little regulation has been put in place following several years of growing concern about these fisheries is, according to the paper, routinely subverted or simply ignored.

An Obscure, Open-Access Trade

The trouble with India’s freshwater fishery is alluded to in the paper’s title—“Uncovering an obscure trade: Threatened freshwater fishes and aquarium pet markets.” “Obscurity,” in one form or another, is a common problem when it comes to resource management in developing nations with resource extraction industries like forestry and fisheries. Lack of management, lack of transparency, lack of scientific data, and lack of regulation all contribute to the precarious position of vulnerable natural resources.

While there have been some efforts to protect endangered endemic fishes in India, fishers—and even more importantly middlemen who purchase from fishers—have proven effective at circumventing regulations. In several examples cited in the paper, endangered species only existing in protected areas where no fishing is allowed are being exported for the aquarium trade.

“In India,” Raghavan and his co-authors write, “the country that harbors the most number of endemic freshwater fishes in continental Asia, collection of such species for the aquarium trade is entirely open-access, unregulated and even encouraged by certain governmental and semi-governmental agencies.”

The paper focuses on the example of the RLTBs, “whose unmanaged collection during the last two decades is associated with severe population declines and an ‘Endangered’ listing in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.” As the authors of the paper recount, the growing global concerns about this fishery did in fact lead to increased regulation in India. In 2008, in the southern Indian state of Kerala, the Department of Fisheries issued a government order, which restricted collection and exports and applied several adaptive management tools. “[R]ecent studies indicate that these regulations were developed with minimum scientific input and offer little protection for the species,” say the authors. For example, a closed season was established based on assumptions about when the fishes breed, but scientific study has shown the assumed breeding times are incorrect. Further, with a lack of reliable, comprehensive data about the trade, it has been difficult to set effective quotas and size restrictions.

Speculation Rather Than Facts?

Raghaven is not without his critics, and some of them worry the paper focuses undue and disproportionate attention on the aquarium trade as the primary threat to the species in question. They point out the data presented in the paper is, at best, incomplete, and without complete data, it is easy to extrapolate conclusions that lack context and are more speculation than fact. They maintain India’s freshwater aquarium trade is “not an obscure one” and that the Marine Products Exports Development Authority (MPDEA) under the Commerce Ministry in India, while not perfect, is doing a competent job of managing the trade. “The fact that the authors were not able to take data from MPEDA and customs in Kochi, India does not mean that the customs and MPEDA do not maintain these files or records,” says one industry insider in India, contradicting statements made in the paper.

Most of the individuals critical of the paper, many of them industry observers with firsthand knowledge of India’s freshwater fishery, agree in principle with the paper’s thesis—that there are significant problems with the freshwater aquarium fishery—but they warn the situation is far more nuanced than the paper suggests. “Mislabeling species and dodging regulations is business as usual in India’s aquarium trade,” says one stakeholder. “Overfishing is common and management is non-existent, but the situation is not as bad as the paper makes it out to be. It’s a very small number of fish that are collected by fishers.”

Many stakeholders in India and abroad are taking an active role in making the Nation’s freshwater aquarium trade better. Stakeholders are addressing issues such as reporting and oversight, supply chain mortality and a lack of emphasis on breeding India’s endemic species in India. In 2012, The Conference on Sustainable Ornamental Fisheries; Way Forward identified key challenges India’s ornamental fish industry will have to face in the future and recommendations for moving forward with a sustainable freshwater aquarium trade reliant on a combination of wild harvest and aquaculture. Identifying challenges and making recommendations for improvements is an important step as India moves along the path to a more sustainable freshwater aquarium trade, but actually implementing those recommendations is the hard part, especially given the coordination required between government and non-government entities.

As one industry insider in India says, “It is high time that the ornamental fish industry in India stands united and look at this issue of conservation and the conservationists seriously and try to justify if the activities carried out by them fall to a sustainable trade.”

Aquarium Trade Unfairly Singled Out?

Critics of the aquarium livestock industry, both freshwater and marine, have a longstanding habit of singling out the trade when other issues are having a far larger impact on ecosystems and species.

“I am not saying that the information provided by the authors on the state of the indigenous Indian species is wrong,” says an industry observer. “I fear that the situation might indeed be very bad for some of the species. I am also not saying that the ornamental fish trade is innocent. It is very likely that there is overfishing in some—possibly in many—areas. But I do get the feeling that a small-volume, high-value trade has been singled out as an appropriate target because of its visibility, rather than because of its size.”

The paper acknowledges other anthropogenic stressors such as sand mining, construction of dams and pollution from pesticides are all contributing to the crisis for many of these highly endemic fishes. Further, the paper points out, some of the species are targeted as both aquarium fishes and food fishes, and indiscriminate fishing and blast fishing are both relatively common in India.

As is frequently cited by advocates of the aquarium trade, collecting fishes for aquarium usage certainly has an impact, but they maintain it’s very small compared to much more significant assaults on aquatic ecosystems. While this may be true, conservationists point out the impact of even minimal fishing on a species restricted to an extremely small area can be profound. An example cited in the paper is the endangered species Garra hughi, the Cardamon Garra, a stone sucker with an endemic range believed to be less than 300 square kilometers (116 sq. mi.). Should this species really be harvested from its extremely small range for the aquarium trade?

Easy Answers, Easy Targets and Shooting Fishes in Barrels

If the aquarium trade’s impact is so minimal compared to other impacts, why does it receive a disproportionate amount of attention from those claiming to be “speaking for the fishes”—people like Robert Wintner or any of the numerous NGOs with anti-trade agendas. One easy answer to this question is that the aquarium trade is, to use a cliché, the lowest hanging fruit. Largely disorganized, underfunded and fragmented, the aquarium trade has proven relatively ineffective at presenting a unified front with a science-based sustainability platform. To continue with the bad idioms, attacking the aquarium trade is a bit like shooting fish in barrel.

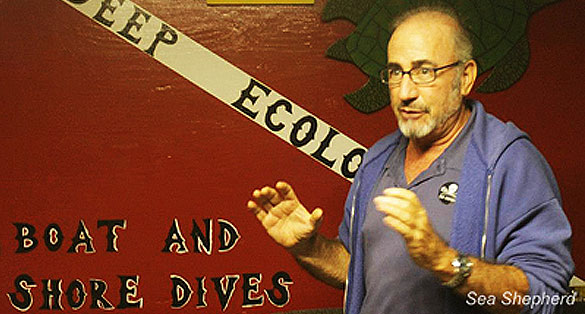

Sea Shepherd Vice-President Robert “Snorkle Bob” Wintner is a veteran campaigner against the aquarium trade and what he calls its “devastating impact” on Hawaii reefs. Photo: Deborah Bassett / Sea Shepherd

That’s the easy answer—that the trade is an easy target. The far more complex answer must take into account the totality of the trade. Sure, far fewer fishes are harvested for aquaria than are harvested for food, and even the most careless aquarium fisher does considerably less damage than a trawl net or blast fishing. But keeping an aquarium is never framed as a necessity the way eating fish is. Hundreds of millions of people worldwide—many in developing nations—depend on eating fish as a critical source of protein, but how many people’s lives hang on keeping an aquarium?

Most people perceive keeping an aquarium as a pastime or hobby—even a luxury one—and as such the environmental impacts associated with collecting aquarium fishes invite greater scrutiny. The average member of the public—a non-aquarist—hears that endangered, endemic fishes in India are being further threatened by collection for fish tanks, and what is he or she to conclude? Thinking about the aquarium trade this way makes it perhaps a little easier to understand why some people believe the easy answer is that if there is to be an aquarium trade at all, it should be 100-percent dependent on aquaculture.

Aquarium Fisheries as Agents of Positive Change

Of course the easy answer of relying exclusively on the farming of fishes, invertebrates, and plants for the aquarium trade fares no better than other easy answers.

While only a small percentage of freshwater fishes originate in the wild, collection impact can, nonetheless, be significant. For example, a well-documented freshwater aquarium fishery in Brazil is showing how sustainable aquarium fisheries can provide some of the best incentive to conserve critical habitat, while at the same time providing important socio-economic development opportunities that keep local fishers and fisher communities connected to the resource.

Unfortunately, the opposite can also be the case as the paper in Biological Conservation contends. While the fishery in Brazil’s middle Rio Negro basin is a model suggesting more sustainable freshwater aquarium fisheries in the developing world could be a real asset from both an environmental and socio-economic standpoint, India’s freshwater aquarium fishery, as presented in the paper, is an example of what can go wrong when a fishery remains largely unregulated and understudied.

As in the example of Brazil’s middle Rio Negro basin freshwater fishery, we know sustainable aquarium fisheries can be primary drivers behind critical ecosystem conservation. We also know sustainable aquarium fisheries can be very good for fishers and fisher communities from a socio-economic standpoint. In some cases, sustainable aquarium fisheries can be the best, most expedient paths to creating real economic incentive to conserve, and there are already pilot programs and plans to turn India’s freshwater aquarium fishery into a success story similar to the middle Rio Negro basin, but these programs need the support of the aquarium trade and, ultimately, aquarists.

The real answer to all of these complex questions is for those of us who care to have the dialog. Freshwater aquarists, like their saltwater counterparts, need to be thinking more about sustainability in the big picture. They need to engage in discussions at their local fish stores, in their clubs and through the aquarium media. They need to be willing to use their purchasing power at the point of sale to make educated choices that will help move the aquarium trade down the path to greater sustainability. And they must, of course, keep in mind that the clock is always ticking for species like the Zebra Loach, a highly endemic species that is thought to occupy less than 400 square kilometers and yet was identified in the Biological Conservation article as one of India’s main aquarium exports.

About the Author

Ret Talbot writes frequently about sustainability issues and is a senior contributing editor of AMAZONAS and CORAL Magazines. He lives with his wife Karen in Rockland, Maine.

SOURCES

Uncovering an obscure trade: Threatened freshwater fishes and the aquarium pet markets

Rajeev Raghavan | Neelesh Dahanukar | Michael F. Tlusty | Andrew L. Rhyne | K. Krishna Kumar | Sanjay Molur | Alison M. Rosser

Biological Conservation

Volume 164, August 2013, Pages 158–169

ABSTRACT

While the collection of fish for the aquarium pet trade has been flagged as a major threat to wild populations, this link is tenuous for the unregulated wild collection of endemic species because of the lack of quantitative data. In this paper, we examine the extent and magnitude of collection and trade of endemic and threatened freshwater fishes from India for the pet markets, and discuss their conservation implications. Using data on aquarium fishes exported from India, we try to understand nature of the trade in terms of species composition, volume, exit points, and importing countries. Most trade in India is carried out under a generic label of “live aquarium fish”; yet despite this fact, we extracted export data for at least thirty endemic species that are listed as threatened in the IUCN Red List. Of the 1.5million individual threatened freshwater fish exported, the major share was contributed by three species; Botia striata (Endangered), Carinotetraodon travancoricus (Vulnerable) and the Red Lined Torpedo Barbs (a species complex primarily consisting of Puntius denisonii and Puntius chalakkudiensis, both ‘Endangered’). Using the endangered Red Lined Torpedo Barbs as a case study, we demonstrate how existing local regulations on aquarium fish collections and trade are poorly enforced, and are of little conservation value. In spite of the fact that several threatened and conservation concern species are routinely exported, India has yet to frame national legislation on freshwater aquarium trade. Our analysis of the trade in wild caught freshwater fishes from two global biodiversity hotspots provides a first assessment of the trade in endangered and threatened species. We suggest that the unmanaged collections of these endemic species could be a much more severe threat to freshwater biodiversity than hitherto recognized, and present realistic options for management.

Twenty years ago we saw the demise of the wild bird trade and the collapse of the cage bird business when, right or wrong, the collection, exportation and sale of wild stock was demonized as the driving force behind a decline of wild populations. As a Pet shop owner and commercial builder of water gardens it became apparent that I was taking a lot from the world’s ecosystems without really knowing the impact of my actions and not giving much back. The truth was location and finances restricted my ability to adequately assess needs and take appropriate action to protect, conserve and rehabilitate (you can not really restore) the environments that my best stock was coming from. However location and finaces did not prevent me from addressing local fisheries and their watersheds. For the last 20 years in partnership with numerous conservation groups, government agencies and schools, my associates and I have been developing and implementing watershed plans on local rivers and streams. What we discovered is a fishery with harvest methods and limits, and open season regulations based on scientific data will rarely, if ever, be the limiting factor in the sustainability of a target species and often brings needed attention and funding to conservation efforts. What does make a difference is implementing a watershed, or landscape, approach to natural resource management. This requires collection of baseline data developing and implementing long term monitoring programs with appropriate oversight and addressing limiting factors through regulation and habitat rehabilitation. During the last 20 years I also discovered, the pet industry does a terrible job when it comes to stewardship of the environments that provided the original stock for our tanks and cages. While the pet industry remains at best silent and often adversarial on conservation issues and programs, other industries that utilize our fisheries lead the charge. The fly fishing industry (tiny compared to the pet industry) top to bottom understands without healthy watersheds and landscapes they are limiting their own potential. The Pet Industry needs an Orvis or Patagonia to make the financial commitment, and the local collectors, shippers and pet shops to do the hands on work on conservation issues. We are past the time of putting back what we take, we have to put back more than we take, or once again through our ignorance and indifference we will get what we deserve. In my opinion.