Rhinogobius zhoui: Beauty with a Fragility Factor

Text & Images by Jutta Bauer

Web Special Excerpt from AMAZONAS Magazine

When the first Rhinogobius zhoui began appearing in the aquarium trade in September 2010, a tremor ran through the goby community. Everybody had to have one. At the time, though, the price was very high, so the first consignment didn’t make a huge splash. I hoped that people would soon be breeding these fishes, but that hasn’t turned out to be easy. As with many new species, a variety of common names have appeared, including Chinese Vermilion Goby, Scarlet Goby, and Flame Goby, and Zhou’s Vermilion Goby.

I obtained my first three Rhinogobius zhoui, two males and a female, from a friend on the goby scene who was keen to keep the species in the hobby and regarded me as fit for this purpose. But I didn’t have much success; right off the bat, the larger male was killed by a large rock that no previous goby had considered as a breeding site.

The remaining pair fairly quickly exhibited symptoms that I also observed later, when I separated a pair for breeding purposes: the male became apathetic and couldn’t be stirred to action by the rather demanding female. The first, hesitant courtship activity soon ceased.

An orgy of posturing

While the importers were hunting for further stocks without success, I had an enormous piece of good luck. An acquaintance who was traveling in China on business found Rhinogobius zhoui offered for sale at a fish market. Unsure of the identification, he sent me a photo that took my breath away: they really were R. zhoui! I mailed him to say that he should buy all the fishes he could find, and that’s how I obtained nine more individuals—three males and six females.

The spectacle that took place when the nine gobies went into my tank was indescribable. My male indulged in an orgy of posturing and the new boys weren’t far behind, while the girls, who arrived plump with eggs, had to wait.

Sometimes I had to smile, as two or three of the males would face off against one other and put on a show, while one of the females sat in the “grandstand” nearby, wobbling around on her egg-filled belly, and watched the “jousting.” But sooner or later it would all become too much for her, and she would turn into a little fury. With inflated gills and mouth pursed she would descend among the contestants, shove the unwanted suitors out of the way, and chase the mate of her choice toward the spawning rock, as if to say, “That’s enough of that! Now let’s get down to business, dear!”

But that was where the problems began. The males were much more interested in each other than in the females. Even when they had established their territories, which were separated by adequate barriers to vision, they kept going on raids. Like robber knights they inspected other males who had just dug their caves, initially just looking with great interest, but in the next moment commandeering their rivals’ caves and triggering the next round of hostilities. Even the domineering, demanding behavior of the most powerful females failed to interest them, so I found the first eggs carelessly abandoned in

a corner.

That wasn’t what I had expected at all. I separated the males and put each with a single female in a 6.5-gallon (25-L) tank. The tanks stood next to one another so that the fishes remained in visual contact. One male remained in the big tank with the rest of the females.

Problems with infections

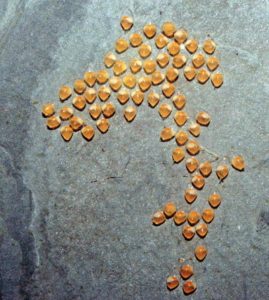

After I had ranted around for a while—because the new arrangement didn’t have the desired effect at all—and even shouted threats at the gobies to the effect that I would send them all off to a beginner, the first spawning finally took place in the big tank. There were 62 eggs, around 4.5 mm long, which promised normal-sized fry. Because the male was again wandering off to do other, much more interesting things, I transferred the clutch to a 3-gallon (12-L) tank, and watched with interest to see what happened next.

Like all members of their genus, Rhinogobius zhoui like to dig their spawning caves beneath slabs of stone.

This time the eggs died off. No matter what I did, there would be one to four white eggs suspended in the clutch next morning. I carefully removed them with forceps. But despite water changes and the addition of a small amount of salt and alder cones, I couldn’t stop this process. A friend advised me to disinfect a tank completely every day and transfer the eggs to it. That helped. But by then there were only 25 eggs left.

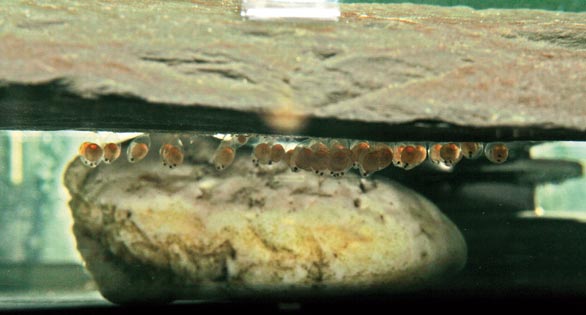

Hatching began after eight days. The larvae had huge yolk sacs and lay on the bottom, completely incapable of movement. There was another major die-off. Despite newly set-up tanks, the young were attacked by bacteria, some inexplicably lost their yolk sacs, and in the end there were just 15 left.

It was seven days before the young could finally begin to move. Even then they were still susceptible and another four died, so that in the end there were 11 left—not a very good yield when compared with other Rhinogobius species.

Vulnerable to Pathogens

Meanwhile, life in the big tank went on as usual. Around four weeks after the first clutch there was a second: 46 eggs, two of them unfertilized. Again, the male showed no interest in brood care, but preferred to poke around all over the aquarium. This time the clutch wasn’t suspended on the underside of a rock, but laid in a tube with a closed end, so I had to break the tube open carefully in order to “fan” the eggs with a gentle current. This clutch was again transferred to a 3-gallon (12-L) tank, and I followed the same procedure. This time the young hatched after 13 days, with huge yolk sacs, and proved no more resilient than the previous batch. Just four young survived from this clutch, despite all the precautionary measures.

After that, spawnings became somewhat more frequent, but new problems surfaced. The eggs weren’t fertilized and were often partly eaten by the male. I got in touch with Zhou Hang, who discovered the species and after whom it is named, and asked him about the habitat. He confirmed what I had already suspected: the fishes live relatively close to a spring in a river, far from the pollution of civilization and without large numbers of other fishes in the vicinity. This suggested that the higher infection pressure that inevitably exists in the aquarium and the build-up of pollutants might lead to infertility in the male.

Frequent large water changes produced the desired success. The subsequent spawns were fertilized, but the male would start to eat the clutch little by little as soon as it was laid. There was no stopping him.

The other males in the smaller tanks failed to perform at all, so after a number of weeks I put them back in the main tank. And now came the next setback. Within a few days the three males I had put back were all dead. The first had visible threads of fungus growing out of his mouth, and the other two died within the next 12 hours with mouths wide-open and gaping, but without threads of fungus. Attempts to treat the disease with fungicides, bactericides, and lots of fresh water met with no success at all.

I presume that there were fairly violent battles for order of rank. The mouth-fighting that takes place during altercations leads to minor damage to the mouth, which apparently becomes infected immediately. The relatively weak immune system probably also plays a part. So in the end there were just one male and six females left. The male was completely overwhelmed by this situation.

A pause in breeding

The offspring developed incredibly slowly. After six weeks the little ones were only 1 cm long. By comparison, Rhinogobius rubromaculatus typically measure .75 inch (2 cm) at the age of four weeks.

After some weeks it could be seen that—just my luck—there were only three males among the 15 youngsters; the rest were females. Nevertheless, I decided to keep them all and hope that the offspring would have lost some of their excessive sensitivity. But that probably wouldn’t become evident until the summer, as their growth continued to be very slow. In the meantime I obtained an additional 10 males from Aquarium Dietzenbach, but they, too, were still very young, and to my great sorrow they had become infected by bacteria as a result of the long journey from China, leading to a major die-off. I was able to stop this after some days via the addition of bactericides, alder cones, and salt, plus large water changes.

At present there is a pause in breeding. It looks as if they have all gone on holiday. No sign of threat display and no courtship. The females are laying no eggs and are all sitting around more or less motionless. Even their food intake has reduced, which I find particularly interesting as I’ve never seen that in any other species before. It remains to be seen if this behavior will alter with the onset of spring. Experiments with prolonging the photoperiod, raising the temperature, and fresh water have failed to bring about any change. The gobies appear to be following an internal clock.

I have tried comparing my experiences keeping these fishes with those of other aquarists. Unfortunately, I don’t know all that many, but some of them who are keeping a group and trying to breed them have confirmed my observations. They, too, have experienced reluctance to breed, egg eating, and very delicate young with very few surviving. At present (winter 2011/2012) their fishes, like mine, are taking a winter break.

It seems that while this Rhinogobius species may be gorgeous, it is also very delicate. We must hope that the offspring will prove hardier, as there are still very few specimens being imported. It is also no longer any wonder that they are found so rarely, as their reproductive strategy—at least in captivity—isn’t conducive to large classes of offspring. All the more important that we continue to try and breed them.

Addendum

From March on, the courtship activity resumed again. The tank-bred males remained very backward and all spawnings have been with the old male, who measures just under 2.5 inches (6 cm), while the young fellows are 2 inches (5 cm).

The eggs are still eaten within the first 24 hours, so I now remove the clutch immediately after spawning and transfer it to a 3-gallon (12-L) nursery tank with a net spawning trap suspended in it. Aeration is provided by a small fountain pump (53 gal/hr, or 200 L/hr) aimed directly at the eggs and producing something of a storm around them.

The mortality rate after hatching initially continued to be high, even after the introduction of the net box, which is intended to prevent the larvae from lying on the bottom.

I eventually had the courage to use a mixture of formalin and malachite green, which is actually meant to be used to prevent infections in garden ponds. I used it sparingly, just three drops per 2.6 gallons (10 L) every two days. My thinking was that if the larvae were dying anyway, I couldn’t make the situation any worse. And, lo and behold, it actually prevents the die-off.

In the case of the first clutch the infection was already in progress, but was stopped by the medication in a few larvae. But the results of the infection were obvious. The little ones were unable to coordinate their movements when they tried to swim, spinning around with their heads always in an oblique position. This led me to suspect increasingly that some sort of infection of the nervious system was leading to the heavy die-off. It would be interesting to know whether other aquarists have observed these symptoms.

But if this infection can be prevented right from the start, the larvae are completely healthy and develop much better than previously. Where the yolk sac previously required around 10 days to be reduced to the extent that the larvae could move, it is now four days until they start to flit around and begin to feed.

References

Li, F., & J.-S. Zhong. 2009. Rhinogobius zhoui, a new goby (Perciformes: Gobiidae) from Guangdong Province, China. Zool Res 30 (3): 327–33.

Mimbon Aquarium News 09/2010: Rhinogobius zhoui, die Flammengrundel.

Special thanks to Mimbon Aquarium, Cologne, for being the first to import this species in 2010.

Very informative, thank you for your work.

I thought both parents took care of the young