Indigenous warriors protest the invasion of their lands by construction crews building roads in preparation for the damming of the Rio Xingu in what would become the world’s third largest hydroelectric power project.

By Louise Watson, Amazonas Staff Report

Images: Rafael Salazar/www.amazonwatch.org

Excerpt from AMAZONAS, November/December 2012

Biologists and human rights observers are calling it an epic disaster in the making, a massive river-damming complex in the heart of the Amazon basin that threatens tens of thousands of native rainforest dwellers and the fish populations that sustain them and enrich the aquarium world.

Belo Monte, the third largest hydroelectric project in the world, is part of the Brazilian government’s plan to power a growing economy and reduce dependence on fossil fuels, but opponents say that there are far more environmentally sound ways to save and generate electricity and that the damage—including the release of huge amounts of methane, a gas 25 times as potent as carbon dioxide—would far outweigh the benefits.

Damming and diversion of the Rio Xingu in Brazil will displace tens of thousands of indigenous peoples in the heart of the Amazon basin and threaten native stocks of fishes caught for food and export to aquarists.

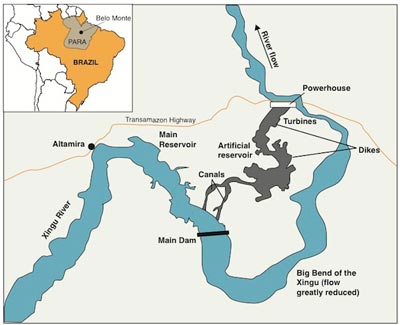

According to Amazon Watch, an NGO founded “to protect the rainforest and advance the rights of the indigenous peoples of the Amazon Basin,” 80 percent of the water in the Xingu River, a major tributary of the Amazon, will be diverted into two giant canals, each one-third of a mile wide, the creation of which would excavate more earth than was moved to build the Panama Canal. The dam would flood 258 square miles (670 km2), over half of which is rainforest, and displace as many as 40,000 people, according to some estimates.

An independent panel of experts made up of scientists from Brazilian research institutions came to the conclusion that the dam project would cause a permanent drought in the area, with the following consequences:

• Fish stocks, which are especially rich and diverse in the Xingu, would be decimated. (Inhabitants of the region get 70 percent of their protein from fish.) The ornamental fish trade, an important source of income for poor fisher families, would be crippled. The tribes whose ancestral lands, homes, and ways of life are threatened include the Kayapó, Arara, Juruna, Araweté, Xikrin, Asurini and Parakanã Indians.

• The reduction in the river’s flow would restrict or prohibit navigation, preventing trade and access to medical care. Below the dam, agriculture would suffer from lack of water; upstream, wells would be contaminated by the rise in the water table and water-borne diseases would proliferate.

• The promise of construction and support jobs would entice up to 100,000 people into the unspoiled region via a network of new roads. These newcomers would compete for about 40,000 jobs and place an untenable burden on already frail physical and social infrastructures. Many of these immigrants are expected to settle in the rainforest and take up illegal logging and ranching.

There is more to the Belo Monte project than meets the eye: Additional upstream dams would be required in order to guarantee year-round power output, because water flow in the Xingu is subject to wide seasonal variations. And 30 percent of the power that would be generated has already been sold to the huge Eletrobras electric utility company, which will resell it to mining operations and other unsustainable and power-intensive industries.

A number of NGOs opposing the dam, including International Rivers, Xingu Vivo, and Amazon Watch, have been joined in their fight by celebrities—including James Cameron, director of the film Avatar, and actress Sigourney Weaver, who starred in the movie. Videos featuring both can be seen on the Amazon Watch website.

Construction of access roads to the site began in March 2011, but those opposed to the dam complex have been cheered in recent weeks as high-level forces have been attempting to halt construction via legal means. Federal judge Souza Prudente, whom many hailed as courageous for championing the rights of indigenous peoples, ordered work to stop in August 2012. The order was overturned within days by the Supreme Federal Court of Brazil. It was the latest in a series of conflicting rulings, and more are expected as worldwide opposition to the plan grows. (The Federal Public Prosecutors’ Office filed an appeal on September 3).

The Zebra Pleco, Hypancistrus zebra, endemic to the Rio Xingu, is one of a number of species whose fate may be affected by the Belo Monte dam project. Image: A. Birger/Creative Commons.

Prudente said, “The court’s decision highlights the urgent need for the Brazilian government and Congress to respect the federal constitution and international agreements on prior consultations with indigenous peoples regarding projects that put their livelihoods and territories at risk. Human rights and environmental protection cannot be subordinated to narrow business interests.”

An incomplete environmental impact assessment, the failure to inform and consult with the people who would be affected, and a judge’s ruling that the project could go ahead without these essential components have angered many, and a number of protests have been staged, including a three-week occupation of the site this June.

Updates

Construction Forging Ahead: Field Update

On the Internet:

International Rivers: http://www.internationalrivers.org

Amazon Watch: http://amazonwatch.org/work/belo-monte-dam

James Cameron, A Message from Pandora:

http://amazonwatch.org/news/2011/0907-message-from-pandora

Sigourney Weaver, Defending the Rivers of the Amazon: http://amazonwatch.org/news/2010/0830-defending-the-rivers-of-the-amazon-sigourney

Survival International: http://www.survivalinternational.org/about/belo-monte-dam

Xingu Vivo (Portuguese only): http://www.xinguvivo.org.br/

Agenda 21 at work!